Modern academic disciplines often and perhaps rightly trace their development to the ancients. Astronomers can look to Ptolemy, philosophers to Plato, and history majors to Herodotus and Thucydides. But for many subjects there are untold and much more recent stories at play. For example, how did the study of political “science” break off from the study of statesmanship and history at large? What brought about the distinctions between the relatively new disciplines of sociology and psychology? And what spawn of Satan unleashed the MBA on this earth? [To answer the latter question, I recommend Matthew Stewart’s The Management Myth, excerpted in the Atlantic here.]

International relations would seem, however, like a fairly innocuous subject. Surely we’ve always been analyzing the relationships between states. But a review by Susan Pederson in the London Review of Books contains shocking revelations on this account. Reiterating arguments from Robert Vitalis’ 2015 White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International Relations, Pederson shows that what is now called international relations was in the early 1900s chiefly concerned with the study of relations between races. The foremost publication of international relations today, Foreign Affairs, even began its life with a different title: The Journal of Race Relations.

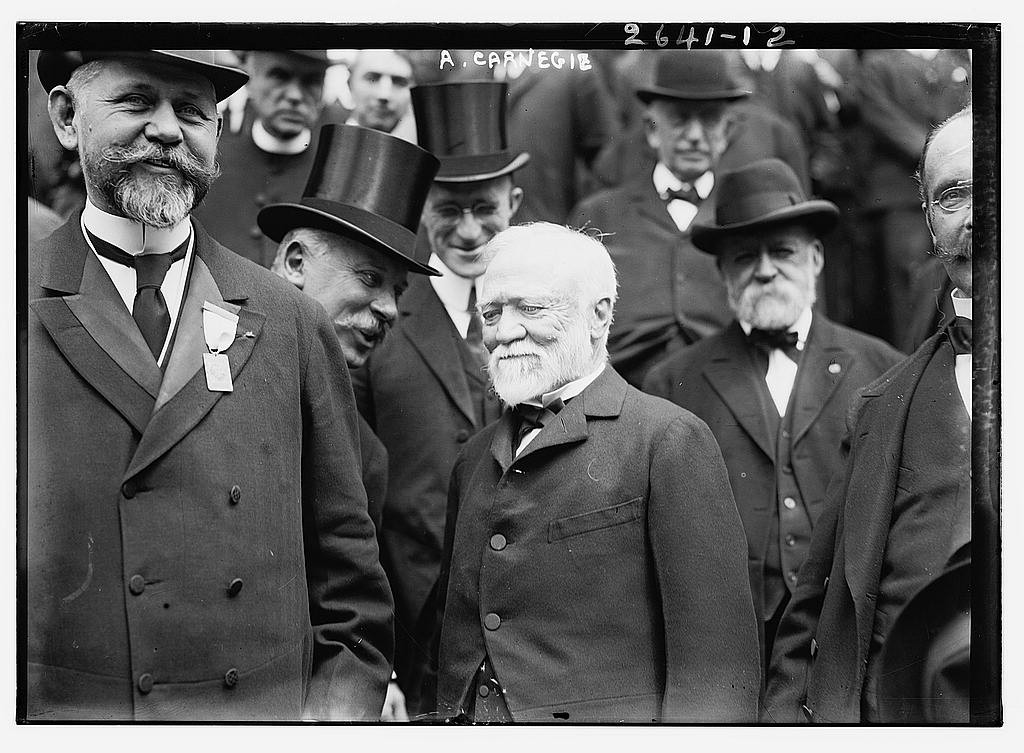

With heavy support from eugenics-minded philanthropic foundations like Carnegie and Rockefeller, international relations was born as the study of how the white race should “manage” the growth of non-white populations that were assumed to be inferior.

“A blunter way to put this, and Vitalis is blunter, is that international relations was supposed to figure out how to preserve white supremacy in a multiracial and increasingly interdependent world. Segregation and Jim Crow had done the trick at home, where non-white populations were in the minority, but how could white America govern its newly annexed and overwhelmingly non-white territories without losing its republican soul? A few white scholars thought the task impossible.

…The ‘hump’ of the profession may not have raged about whites’ inalienable ‘right to their racial heritage’, but Vitalis could find no white international relations scholar in this era who directly challenged white privilege by supporting equal citizenship rights and colonial self-determination. All were, as the historian of anthropology George Stocking put it, ‘evolutionists’: that is, they assimilated ‘races’ to ‘stages’ of the human evolutionary past, and then assumed each had to develop separately and at its own pace. After all, these were the principles that governed race relations in the United States.”