For conservative givers, a sober assessment, with high stakes.

“The world of philanthropy abounds with contradictions and absurdities,” National Association of Scholars (NAS) chairman Keith Whitaker said as he introduced a thoughtful 90-minute NAS webinar on philanthropy and higher education earlier this week. “Many philanthropists consider themselves good liberals,” for example, “yet aim at ‘structural change’ through undemocratic means supported by vastly concentrated financial wealth. Donors who earned their wealth through private enterprise, made possible by a system of individual rights and law, often support programs whose goal is to overthrow that system.”

After noting the relative dearth of conservative philanthropic interest in predominantly liberal and progressive higher education, Whitaker noted that

conservative philanthropy has a crucial role to play in higher education, and not only as a reaction against the Left. The traditional attraction of higher education to philanthropists is that it is about promoting excellence rather than remediating deficiencies. Food, shelter, health—all these obviously matter to living. But higher education is about living well—about developing the human mind and heart to their highest potentials.

Whitaker asked, “Has higher education lived up to this promise? Are we not just more comfortable and longer-lived,” he continued, deepening the question and offering a challenge, “but more intelligent, more serious, kinder, less inclined to vulgarity and cruelty and violence? If not, then that is an opening for a truly conservative philanthropy: to arrest further decline, and return to a better, more solid ground, in pursuing human excellence.”

To answer those questions and outline past and potential future ways for conservatives to try meeting that challenge, the webinar then heard from retired Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation vice president for program and The Giving Review co-editor Daniel P. Schmidt and Capital Research Center president Scott Walter.

Convention and curiosity

Schmidt described the Bradley Foundation’s experience with and approach toward higher-education grantmaking during his three decades on the program staff there, including some of its successes and failures.

Schmidt

“We thought that this was an opportunity to challenge convention,” Schmidt said. “Ideas mattered to us—as they do to not just conservatives, but certainly to conservatives—and that’s especially true in higher education.”

Specifically, among other projects, he described the conception and formation of the Bradley Graduate and Post-Graduate Fellowship Program. “We refused to pay any overhead, he said. “There were a few verbal tussles over the phone with administrators and development people” about that, “but you know, we were able to stick” with that stance.

Other examples, discussed by both Schmidt and Walter, include support of: colleges and universities themselves, organizations that protect and defend faculty members’ roles and rights, including those within specific academic disciplines; and groups that assist and connect students, including those that expose them to a wider range of thought.

All of Bradley’s higher-ed grants were based on “the importance of excellence and merit,” Schmidt said, and that would be the best advice about how others should base their thinking of any grantmaking in the area, too. We should “understand the stakes involved here,” and that they ultimately include the understanding and acceptance of that which undergirds Western civilization itself.

Generally right now, he lamented during the session’s question-and-answer component, “we’re a little lacking in curiosity and imagination. In fact, philanthropy is not excused from that.”

Knowing the odds

Walter said that there are two questions facing donors interested in exploring higher-ed giving. “First, should I fund in higher ed at all? And my answer would be absolutely yes, but you ought to recognize that it's going to be very hard. The odds are against you. You have to fight very hard and very smart.”

Walter

The second question, he said,

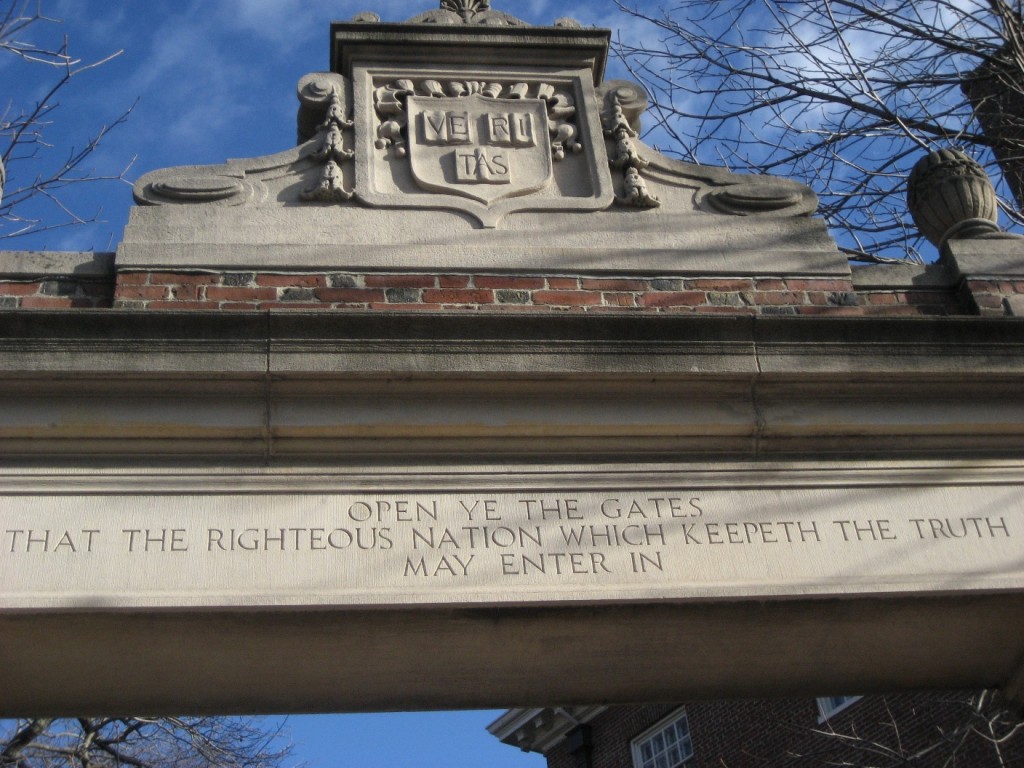

quickly becomes, well, what sort of higher-ed place should I fund? Should I only fund really prestigious places, because that's where the real leverage is—or on the other hand, should I despair of Harvard and Yale and Chicago and the like, and instead only fund at safe places, something like a Hillsdale or the University of Dallas or Grove City or something like that?

And my answer to that is, both. I think neither type of place should be written off.

As conservatives, Walter soberly concluded, “we should never surrender, but we should be very sober about just what terrible odds we all face” in the higher-ed area.

The Giving Review hopes to soon feature an overview of grantmaking options in higher ed.