Biographies of great philanthropists fill a thick shelf. But films about philanthropists are vanishingly small. If the data in the Internet Movie Database is correct, there has never been a movie or TV show featuring Andrew Carnegie or John D. Rockefeller as a character. In fact, there are more films with a fictional John D. Rockefeller 3rd (one) than there are films about his more famous grandfather.

This is what makes Aviva Kempner’s documentary Rosenwald unusual. Kempner does documentaries about Jewish subjects, including a film about baseball slugger Hank Greenberg and another about the radio and television show “The Goldbergs.” She is an efficient storyteller, who conducted a great many interviews, including with two Rosenwald biographers: Peter Ascoli, a grandson of Julius Rosenwald, and Stephanie Deutsch, who is married to a great-grandson of Rosenwald. People who see this film will get a reasonably accurate account of Rosenwald’s life and philanthropic achievements.

Like many Jewish immigrants, the Rosenwald family came to America and began peddling, which consisted of traveling in a cart loaded with pots, pans, and other sundries that frontier families might need. The funniest moment in this film is a clip from “Rawhide,” where a peddler, explaining what he does, tries to teach Clint Eastwood’s character Rowdy Yates Yiddish.

Julius Rosenwald quit school when he was 16 and entered his father’s clothing business. Eventually he discovered Richard Sears, co-founder of Sears, Roebuck, who became Rosenwald’s best customer and who eventually brought Rosenwald in as a partner.

There are still Sears stores somewhere, but Karen Heller, in her piece in the Washington Post about this film and Rosenwald’s philanthropic legacy, has to explain that “Sears was the Amazon.com of its day.” The problem was that Richard Sears was one of history’s great salesmen, but hated to handle orders. Orders were thrown into baskets where they would sit for weeks or months. Frequently a customer who placed an order would have to wait weeks or months, only to get the wrong product or to be told that a product was out of stock.

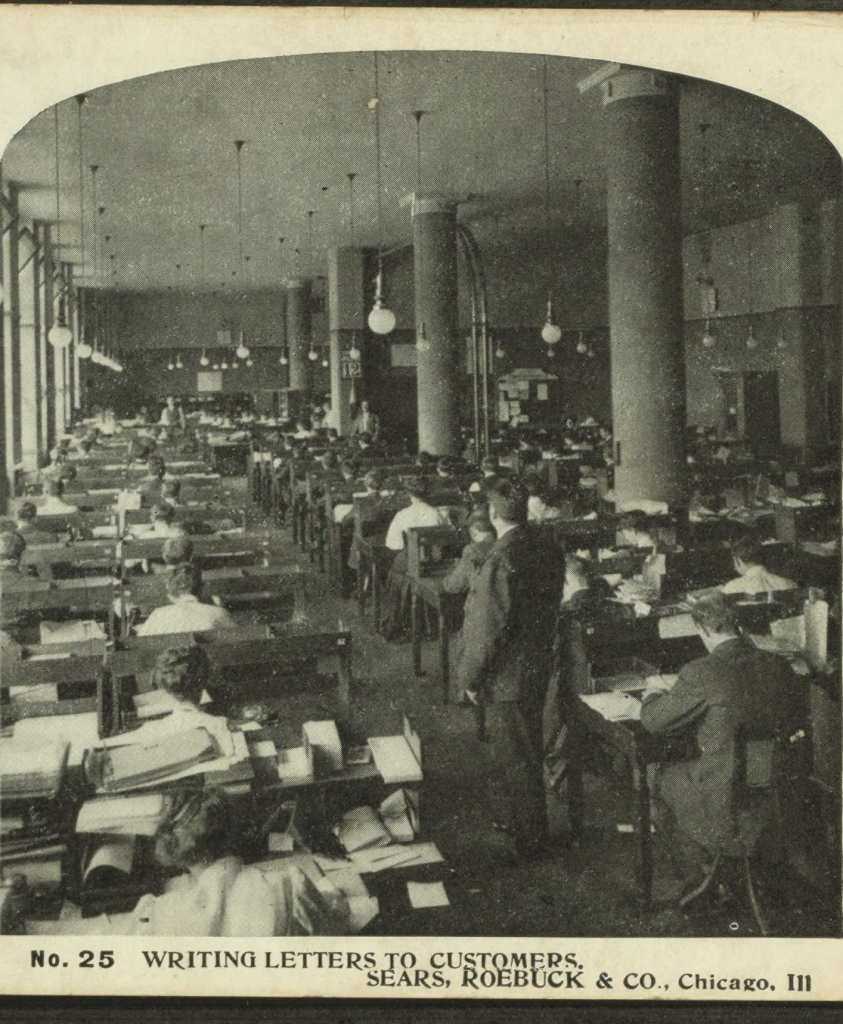

Rosenwald, working with Otto C. Doering, Sears’s chief of operations, opened a 40,000 square foot warehouse where orders entered the warehouse in one place, and then slips went to various parts of the warehouse until they were filled. In addition, Rosenwald insisted that all products in the Sears catalog be described honestly.

“Sell honest merchandise for less money and people will buy,” Rosenwald declared. “Treat people fairly and honestly and generously and their response will be fair and honest and generous.”

In 1908, Richard Sears was pushed out of Sears, Roebuck and Julius Rosenwald became the company’s chairman, a position he held until his death in 1932. By 1912 he had made enough money to be a philanthropist. He had all sorts of interests, including aiding Jews in Palestine and inspiring Chicago to create the Museum of Science and Industry. But his primary philanthropic effort was in aiding African-Americans.

In 1911, Rosenwald read Booker T. Washington’s autobiography Up From Slavery. He invited Washington to Chicago, and they decided to work on a series of projects. He began by an effort to build YMCAs for African-Americans. These YMCAs were more than gyms; they were also hotels that provided places for black travelers to stay, which was particularly important in segregated cities.

Rosenwald also built social housing for blacks in the Bronzeville section of Chicago. Rosenwald regarded house construction as a program-related investment rather than philanthropy, but the apartments, opened in 1929 housed many eminent blacks and were managed for decades by the mother of music producer Quincy Jones. The buildings were closed in 2000 and crumbled for nearly 15 years, but a new developer promises to reopen them as “Rosenwald Courts” in 2016.

But Rosenwald’s greatest achievement was building schools for African-Americans in the South. By the time of his death in 1932, he had helped construct 5,357 schools and contributed $4.4 million towards the construction of the schools. But Rosenwald only put up a third of the cost for the schools; another third came from government, but the most important third came from the recipients of the aid. In addition, African-Americans had to construct the building, in part to give blacks experience at constructing buildings.

By 1925, the school-building effort had waned and Rosenwald shifted his effort to cultural activities, through the creation of the Julius Rosenwald Fund. Kempner shows that the fund’s effort to aid talented young African-American artists, scientists, and scholars had a very successful record, since three recipients of their aid were singer Marian Anderson, Dr. Charles Drew, a surgeon and expert on blood plasma, and Ralph Bunche, a diplomat and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. The fund also aided some white artists, such as singer Woody Guthrie.

It should be noted that this film, although very straightforward, is nonetheless a left-wing celebration, capped with interviews with two descendants of Eleanor Roosevelt (who served on the Rosenwald Fund board). The director, in her credits, dedicates the film to, among other things, “renaming the Washington football team.” Many of Rosenwald’s descendants are prominent liberal philanthropists. (Among them was Rosenwald’s grandson, Philip Stern. I edited Stern’s last book, Still The Best Congress Money Can Buy, and met with Stern twice while editing the book.)

There are three lessons conservatives can learn from Julius Rosenwald’s philanthropy.

The first, and most important, is Rosenwald’s firm and eloquent defense of term limits for foundations. If I were teaching the history of philanthropy, I would require students to read Rosenwald’s 1929 Atlantic Monthly article “Principles of Public Giving.” His arguments against perpetual foundations are as eloquent and forceful now as they were in his time.

Second, the reason Rosenwald gave matching grants for his African-American schools was in part due to Booker T. Washington’s philosophy of self-reliance. He wanted to make sure that parents who sent their children to “Rosenwald schools” were partners in their construction, that they had what we could call “sweat equity” in the construction of these schools. He didn’t want these parents to passively accept a freebie.

Daniel Boorstin once observed, “no one would be helped” by Rosenwald’s aid “unless the person himself was willing to make an effort to help himself. The passive beneficiary had no place in this scheme.”

Finally, the success of the Rosenwald Fund in the arts reminds us that it is far better to give small grants to young artists than large grants to old ones. Far too often, risk-averse program officers love lavishing massive prizes on well-credentialed people at the end of their careers, because that way they won’t make a mistake. But it is the Millennials, not the Baby Boomers, who need help from foundations interested in the arts.

Rosenwald is a provocative and informative film that both grant makers and grant recipients need to see.

Note: There is an alternative interpretation of aid by Northern philanthropists towards Southern African-Americans, namely that such aid stifled blacks from developing their own independent educational institutions. Eric Anderson and Alfred A. Moss Jr, forcefully make this case in their book Dangerous Donations, which I reviewed for Philanthropy.

1 thought on “Rosenwald, a philanthropist in film”