Parsing a few Sections, Parts, columns, and Schedules.

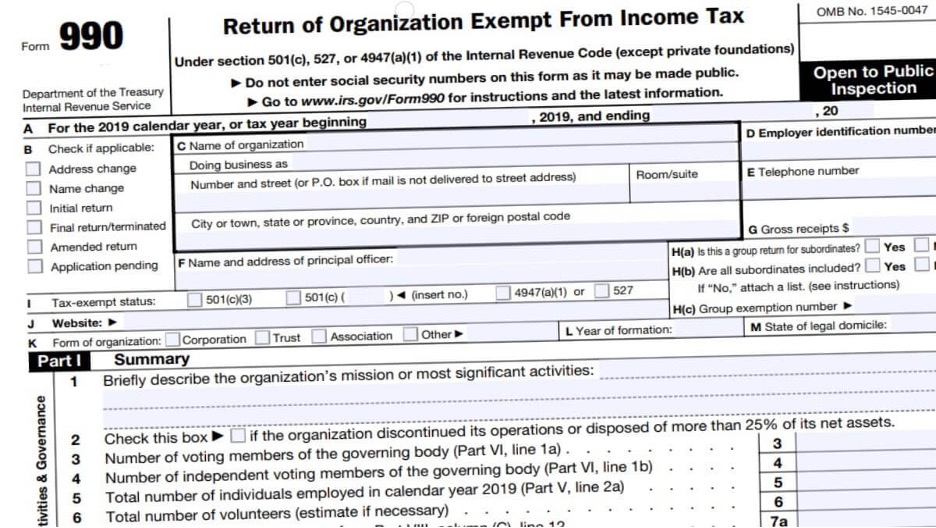

Each year, tax-exempt, nonprofit organizations and foundations are required to file returns with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Most of these groups—such as those formed as charities under § 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, social-welfare organizations under § 501(c)(4), or labor unions under § 501(c)(5)—file Form 990, while § 501(c)(3) private foundations file Form 990-PF. These filings are made publicly available on the IRS website and via a number of private resources.

Forms 990 and 990-PF provide a great deal of information on the filing organization’s financials, operations, leadership, and more. They could, however, be made better. Here are some suggested revisions to improve the current Form 990/990-PF—and, by extension, the ability of Americans to evaluate tax-exempt nonprofits.

Suggestion No. 1: Enforce foundation investment disclosures

As explored in detail here, current IRS instructions require private foundations to attach certain schedules to their Form 990-PFs listing and describing the specific assets in which their endowments are invested. In practice, however, many foundations do not provide meaningful detail on individual holdings. For example, a foundation might simply report a giant lump sum as invested in “corporate stock” or in “global equity funds,” without listing any of the individual corporations or funds in which the money is invested.

The only exception is for government obligations, which the instructions specifically allow to be reported as lump sums based on issuer category (federal or municipal bonds, for example). The IRS should revise its instructions for Part II, Balance Sheets, saying that all other types of investments must be itemized to the extent practicable on the required schedules and noting that lump-sum reporting is unacceptable.

Suggestion No. 2: Improve grants reporting

Many nonprofits have similar names, operate under more than one name (for example, an entity “doing business as” another name), are commonly referred to by different variations on their name, or exist as one of a number of nearly identically named (but legally distinct) affiliates or chapters—sometimes sharing the same address. This can cause considerable confusion when attempting to analyze reported grants, because it is not always clear exactly which group is the one that received the grant.

The Form 990 largely addresses this problem by including a column for the recipient’s employer identification number (EIN). This is a unique, nine-digit code that can usually—assuming meticulous accuracy on the part of the filer—be used to unambiguously identify a recipient. The Form 990-PF used by foundations, however, does not include this column. While foundations may sometimes make grants to recipients that do not have an EIN, the IRS should add a column to the Form 990-PF wherein the grantee’s EIN is to be listed, if and when applicable, which is almost always.

Another issue with grants reporting involves the use of attachments, rather than listing grants directly in the filing. Occasionally, these attachments are not included with the rest of the Form 990/990-PF when it is released to the public.

For example, the Rockefeller Family Fund reported paying out more than $17 million worth of grants on its 2019 Form 990, which is available on the IRS website. The attached Schedule I—which is used to report all grants in excess of $5,000 made to domestic recipients—directs readers to “See Schedule I-1,” but no such schedule is attached to the filing. Anyone wishing to see the Rockefeller Family Fund’s 2019 grantees cannot find this information on its Form 990 as posted by the IRS.

The instructions should either clarify that grants must be listed directly in the prescribed sections of the form or the IRS must ensure that important attachments are always, in fact, attached to the copy made available for public disclosure.

Finally, foundations report grants made to foreign entities on the Form 990-PF in the same manner that they report grants made to domestic entities—including listing the name and address of the foreign recipient. Nonprofits filing the Form 990, however, are instructed to omit the names of foreign grant recipients on Part II of the applicable Schedule F. They disclose only the purpose of the grant, the amount, and the geographic region.

An IRS background paper detailing 2008 revisions to the Form 990 explained that the idea of reporting identifying information about foreign grantees prompted commenters to raise security concerns about “work in certain unsafe foreign areas.” The IRS should reconsider whether such legitimate concerns are nevertheless outweighed by the significant public interest in foreign-grants reporting—particularly since the Form 990-PF freely discloses this information—or if there are alternative methods of addressing these concerns.

Suggestion No. 3: Include fiscally sponsored projects

Fiscal sponsorship presents some unique issues for the Form 990. Briefly, a fiscal sponsorship is an arrangement through which an existing tax-exempt nonprofit houses a “project” group that does not have its own tax-exempt status. The sponsor provides administrative services to—and in the case of § 501(c)(3) projects, accepts tax-deductible donations on behalf of—the project. Sponsors generally charge a fee for these services.

Grants or contributions made to the project are technically made to the fiscal sponsor, and projects do not file their own Form 990s with the IRS. This greatly limits the public’s ability to obtain information about the project, including its financials, leadership, and more. This can become rather important when a project achieves national prominence for its activism on controversial sociopolitical issues—as occurred in the case of the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation in 2020, for a recent example.

Some have suggested fiscal-sponsorship reforms, including requiring both the sponsoring organization and the project to file separate 990s. Another idea is to simply modify the Form 990 to include a new schedule solely for listing any projects sponsored by the filing nonprofit. That schedule could require basic information about each project—such as its name and address, simplified financials, the identities of executive leadership, the date on which it became a sponsored project, and whether or not the project has applied for its own tax-exempt status.

On the funding side, a simple change to the instructions for both Form 990’s Schedule I and Form 990-PF’s Part XIV could significantly improve transparency regarding grants made to sponsored projects. The IRS should instruct filers who have made a grant to a nonprofit for the purpose of supporting one of that nonprofit’s sponsored projects to clearly indicate as such in the grant description/purpose column of their Form 990/990-PF. Some organizations already do this, but the practice should be universal.

Suggestion No. 4: Expand highest-paid employee and contractor disclosures

In addition to requiring the filing organization to identify certain officers and directors and disclose how much each was paid during the year, both the Form 990 and 990-PF also require a list of the organization’s top five highest-paid employees and highest-paid independent contractors. The threshold for listing both an employee and a contractor is $100,000 on the Form 990 and $50,000 on the Form 990-PF. Though only the top five highest-paid employees and contractors must be specifically named, the filing organization must also report the total number of each who were paid in excess of those thresholds during the year.

Some nonprofits and foundations have numerous highly compensated employees and contractors. The five individuals listed on Stanford University’s 2019 Form 990 were paid amounts ranging from about $2.2 million to $4.5 million that year. The lowest-paid “highest-paid” employee at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in 2019 still made more than $1 million. The New Venture Fund reported paying more than $100,000 to 198 different contractors in 2020, yet it was only required to report the top five (including almost $27 million paid to Arabella Advisors alone).

The sections for listing the highest-paid employees and independent contractors on both the Form 990 and 990-PF should be expanded to allow for more-extensive disclosure—perhaps the top 15 or 20 in each category, if applicable. A threshold dollar figure for reporting should still be maintained, and there are arguments that can be made for whether it should be raised or kept at its current level.

While raising the current thresholds could account for inflation, they could perhaps just be kept at current levels, but with more-extensive reporting of contractors who perform smaller-dollar services for a number of different nonprofits, and who are thus influential in the aggregate. The IRS could also consider utilizing different thresholds for employees and independent contractors.

An invitation for consideration

These suggestions are not meant to be exhaustive. Indeed, those who regularly work with the Forms 990 and 990-PF may have additional or differing thoughts on how they may be modified or improved. Because they often serve as the only means through which the public can obtain detailed information about a nonprofit’s financials and operations, regularly considering how these forms may be enhanced serves an important public purpose.