Bob Woodson, my mentor and friend for 40 years, published an op-ed earlier this week in The Wall Street Journal, “Personal Responsibility and the Coronavirus.” As he noted, “When Jerome Adams, the African-American U.S. surgeon general, made an impassioned appeal to segments of the black community to take more responsibility for their actions as a means of reducing their risk, he was demeaned and attacked by the black elite race-grievance merchants.”

I once had the honor of being a speechwriter for another distinguished African-American physician, Dr. Louis Sullivan, when he served in President George H. W. Bush’s cabinet as Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Sullivan was a hematologist with a particular interest in sickle cell anemia, a chronic disease that disproportionately afflicts African-Americans. He also founded and was the first president of the Morehouse School of Medicine.

Although Sullivan has been a life-long champion for directing more medical resources to the health of minority communities—and for expanding the number of minorities in health care—he, like Adams, has frequently called upon those communities to assume more responsibility for personal choices that lead to poor outcomes. As Woodson noted in his op-ed, one of the reasons for the “disproportionate number of black Americans … falling victim to Covid-19” is the “higher prevalence among blacks of pre-existing conditions such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension.” In virtually every speech before minority audiences, both as medical-school president and HHS Secretary, Sullivan hammered away at the fact that these conditions were to some extent remediable by more responsible personal choices.

Like Adams, Sullivan too paid a price for serving a Republican president who, according to the elites, could only be hostile to African-Americans. California Democrat Rep. Pete Stark, who was white, went so far as to say that “Louis Sullivan comes as close to being a disgrace to his profession and his race as anybody I have seen in the cabinet.” Stark later apologized, but only after Sullivan demanded it, pointing out that “I don’t live on Pete Stark’s plantation.”

In spite of these criticisms, Sullivan persisted with his call to personal responsibility for health outcomes, alongside his strenuous efforts to increase the availability of quality medical interventions. Indeed, he came to incorporate in many of his speeches the need for all Americans to embrace a new “culture of character,” not only to combat preventable diseases, but also to improve the overall moral quality of national life.

Sullivan launched his call for a culture of character in a speech at a school-wide convocation in the chapel of Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Ala., on September 10, 1989. It is as relevant, and as courageous, as it was 30 years ago, and so the editors of The Giving Review thought it appropriate to bring the text to a wider audience.

It is truly an honor to appear this morning before the faculty and students of Tuskegee University—an institution rich with history, meaning, accomplishment, and hope.

As I entered your beautiful campus this morning, I could not help but admire the grandeur and grace of Tuskegee’s buildings and facilities.

Many of them, I know, are recently built, and full of the very latest and best scientific and technological equipment, both for teaching and for research. Tuskegee is clearly prepared for the challenges of the 21st Century—prepared to provide her students with the intellectual and technological skills necessary to meet the demands of the new millennium.

But here and there on the campus, I noticed some older buildings, as well. Some of them, I understand, go back to the very first days of Tuskegee and were in fact constructed by the students themselves, from bricks they had made in their own kilns.

How fortunate you are that, alongside your magnificent, new structures pointing the way into the next century, stand reminders of Tuskegee’s early days, and of her strong and venerable traditions!

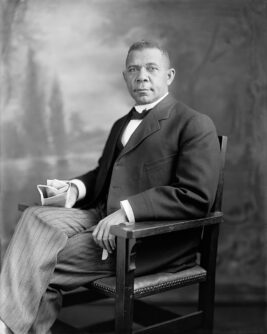

This morning, I want to emphasize another tradition—one that Booker T. Washington also considered important. Each Sunday, as long as he was president, he would gather together the students of Tuskegee for an informal talk. His message was always the same: the Tuskegee student must develop not only a quick, agile mind, he would insist, but along with it, a strong, unassailable character, as well. For, as he put it, “character, not circumstances, makes the man.”

[caption id="attachment_72176" align="alignnone" width="267"] Booker T. Washington (Wikimedia Commons)[/caption]

Booker T. Washington (Wikimedia Commons)[/caption]

Well, it’s Sunday, and the students and faculty of Tuskegee are here assembled. And, although I may be no Booker T. Washington, I do want to say a few words about the importance of character—for the student of Tuskegee, for the citizen of the United States.

Now, I know “character” sounds like one of those ideas that our grandparents and great-grandparents used to talk about. But someday, you’ll have the same experience I’ve had—you’ll discover your grandparents were right about a lot of things. And the critical importance of character is one of them.

Character has also been an important idea to the leadership of the Black community throughout our history. In earlier times, Frederick Douglass insisted that, “with character, we shall be powerful. Nothing can harm us long when we get character.” And in our time, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., reminded us that “intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.”

What do we mean by character, and why is it so important? First, character means courage. We usually think of courage as a virtue exhibited in battle. That kind of courage is certainly no stranger to Tuskegee—the Tuskegee Airmen covered themselves with glory, through their brave exploits during the Second World War. That tradition of courage is kept alive today in Tuskegee’s strong, proud ROTC program.

But there is another kind of courage, as well—the kind exhibited in one of Booker T. Washington’s favorite stories about Frederick Douglass. Once Douglass was taking a train through Pennsylvania, and was forced to ride in the baggage car, despite having paid the same fare as other passengers. Some of the white passengers came back and apologized to Douglass for being “degraded in this manner.”

But, as Washington reports, “Mr. Douglass straightened himself up on the box upon which he was sitting and replied: ‘They cannot degrade Frederick Douglass. The soul that is within me no man can degrade.’”

Today, we are no longer forced to ride in the baggage car. We ride first class. We are the engineers who drive the train. We are the designers who build the train. Someday, we will be the owners of the railroad. And we learned how to do all this at institutions like Tuskegee!

Nonetheless, we still need courage to live in American society today. As President Bush recently reminded us,

Discrimination still exists. Racial hatred—born of ignorance and inhumanity—still exists. The day of the poll tax is over, the day of Jim Crow is gone. Today, bigotry and bias may take more subtle forms. But they persist—and as long as they do, our work is not over.

President Bush’s administration is completely committed to reaching out to minorities, to securing for them a full and equal share in this nation’s life. He recently affirmed, in no uncertain terms, “We will not tolerate discrimination, bigotry, or bias of any kind—period.” You may be sure that, at the Department of Health and Human Services—and throughout the government—we take that charge very seriously.

But meanwhile, as individuals, we must have the courage to confront discrimination wherever it exists, the courage to insist on our rights, the courage to continue the struggle for freedom and justice begun so many generations ago.

Above all, we must have the courage to face bigotry and racial hatred in the spirit of Frederick Douglass. Even as we insist that society treat us with dignity and equality, we must not permit anything that society does to us, or omits to do for us, hinder or delay our progress, our development—our quest for character. For the souls that are within us, no one can degrade.

If character means the courage to insist on our rights, it also means the willingness to live up to our responsibilities. Above all, we must be willing to assume responsibility for our own actions and behavior—to exercise self-control, self-discipline, and self-government in our personal lives. This notion of responsibility is the second aspect of character I’d like to discuss this morning.

The idea of personal responsibility is close to the heart of the Tuskegee creed. For all the hardships and tribulations his people faced, Booker T. Washington never tired of insisting that their salvation ultimately must come from within, from the development of responsible, self-disciplined behavior.

And for all the differences other Black leaders may have had with Mr. Washington, most of them agreed that, in the words of W.E.B. DuBois, the Black community would be saved by “a vast work of self-reformation,” and by learning to “do for themselves.”

We desperately need to strengthen the idea of personal responsibility within our community today. Let me give you just one example where this need is so apparent, in an area of great concern to me—namely, the health of our people.

In spite of improvements in many areas over the past several decades, there is a tremendous and growing disparity between the health of our minority populations and that of the white population. Blacks, on average, have a death rate one-and-a-half times higher than that of whites, and Black life expectancy at birth is actually falling, rather than rising.

We have identified the causes of death that bear disproportionately on our minority populations. They include cancer; cardiovascular disease and stroke; chemical dependency; diabetes; homicide, suicide, and accidents; infant mortality; and AIDS.

President Bush and I are determined to do all within our power to address the disparity in health, and the causes of it.

To address the nation’s shocking infant-mortality rate, we’ve asked for an expansion of Medicaid, to bring improved health services to pregnant mothers and infants. We are also seeking an increase in funding for the Head Start program.

To meet the AIDS epidemic, spending on research and prevention has grown to $1.3 billion for fiscal year 1989, which is a dramatic jump from the $5.6 million spent in 1982.

To cope with the growing youth homicide rate, we will soon launch a major public-information campaign to help youngsters in our neighborhoods find alternatives to violence.

Finally, in the area of drug abuse and chemical dependency, just five days ago, President Bush unveiled a comprehensive new strategy designed to reduce both the supply of, and demand for, illicit drugs in this country.

It is a strong, effective program, and my department is fully committed to making it work, by reinforcing and improving our prevention and treatment programs.

Nonetheless, for all the dollars we spend in Washington—for all the programs and initiatives we launch—the fact is that unless we—you and I—begin to change the way we care for ourselves, and those around us, we will not make significant progress against these blights. We must exercise more personal responsibility in the way we live, and the way we care for our health. We must “do for ourselves.”

Infant mortality can be reduced, if we can get the word to prospective mothers that their diet and behavior during pregnancy have a critical impact on the health and welfare of their children.

Violent deaths in our communities can be reduced, if our own communities will come together to preserve the peace of our neighborhoods, and the lives of our young people.

Drug abuse can be halted, if we stop condoning it by our silence—if we stop turning the other way when family members, friends, and coworkers engage in drug abuse. We must get the message out in our communities—no more tolerance for drug use.

The AIDS epidemic can be contained, if we can overcome our denial—the belief that “it can’t happen to me”—and take the necessary precautions to protect ourselves and those around us.

Likewise, many other afflictions burdening the Black community—cancer, stroke, diabetes, and hypertension among them—can be significantly alleviated, if we can get the appropriate health information to our citizens, and if they will then take responsibility for disease prevention and health-maintenance activities.

In fact, one study shows that better control of fewer than 10 risk factors—including poor diet, infrequent exercise, use of tobacco and drugs, and abuse of alcohol—could prevent between 40 and 70 percent of all premature deaths, a third of all cases of acute disability, and two-thirds of all cases of chronic disability.

We need to carry a very strong and clear message to our communities: improve your diet; reduce your consumption of alcohol and tobacco; increase your exercise; and increase your attention to your health needs, with a goal of maintaining and improving your health status.

Above all, that message must be: take personal responsibility for the way you live, and how you care for yourself. Nothing less is required, if we are to reduce the disparity in the health of this nation.

Along with responsibility for ourselves, we must also exercise responsibility for others—our family, our neighborhood, our community. We must learn to serve. The idea of service is the third and final aspect of character I’d like to discuss this morning.

Service is the very essence of the Tuskegee tradition. You may have heard the story of George Washington Carver’s decision to join the faculty here, at the beginning of a stunningly productive career in agricultural and synthetics research.

President Booker T. Washington sent Carver a letter, at his teaching post at Iowa State University. “I cannot offer you money, position, or fame,” the letter said.

“The first two you have. The last … you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up! I offer you in their place work—hard, hard work—the task of bringing a people from … poverty and waste to full manhood.”

Carver read the letter twice, tore a sheet from the notebook in which he was working, and wrote a reply on the spot. Several days later, President Washington opened the letter, and above the signature “G. W. Carver,” was this simple but eloquent response: “I will come.”

Today, more than ever, your community calls to you for help. It asks you to undertake work—hard, hard work—in the struggle to lift our people from poverty, ill health, and lost hope; to prosperity, good health, and a new promise of fulfillment and happiness.

When my friend on the Tuskegee nursing faculty, Dr. Lauranne Sams, tells you that we need more nurses—and we do, just as we need more doctors, dentists, researchers, medical technologists. and therapists—I hope you will respond, in the best Tuskegee tradition, “I will come.”

When my friend Veterinary Dean Dr. Walter Bowie tells you we need more veterinarians—and we do, just as we need more social workers, engineers, and business graduates—I hope you will respond, in the best Tuskegee tradition, “I will come.”

And when my friend President Benjamin Payton tells you that, regardless of your chosen profession, we need you as role models, as examples, to stand before our people as symbols that hard work, diligence, and character pay off—I hope you will respond, in the best Tuskegee tradition, “I will come.”

Courage, responsibility, service—these are the hallmarks of character. But how are we to acquire these attributes?

You in this room today are more fortunate than many in this regard. For Tuskegee has never forgotten that the development of character is an essential part of education. As Tuskegee’s “Statement of Purpose” notes, your programs are designed to teach “the importance of moral and spiritual values, to enable students not only to pursue careers but to lead lives that are personally satisfying and socially responsible.”

In your liberal-arts studies, you will learn what great men and women through the ages have said about character, and how to go about developing it. You will learn how much character meant to Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Martin Luther King, Jr., and many others.

In your studies, through diligence, effort, and application, in curricula that demand much of you and stretch your abilities, you will learn personal habits like self-discipline and responsibility—habits that will reward you for the rest of your life.

Above all, you will discover the path to character within the four walls of this chapel—in the instruction of Dr. James Massey, and in the promise of this hallowed place that whoever comes to the Cross will possess not only character on this earth, but life everlasting, as well.

[caption id="attachment_72179" align="alignnone" width="500"] Tuskegee Chapel (Wikimedia Commons)[/caption]

Tuskegee Chapel (Wikimedia Commons)[/caption]

Some will say that it’s asking too much of our community to strive for character in today’s world. After all, doesn’t the culture around us bombard us constantly with the message that ideas like character and responsibility are old-fashioned, quaint, and naive? Don’t we hear daily the celebration of self-centeredness, irresponsibility, hedonism, and self-indulgence?

We do indeed. And it is asking much of our community to pursue character, when so many around us are indulging themselves. But character we must have, for it is the only path to health, to prosperity, and to personal fulfillment in this life, and to countless blessings in the next.

More than that. We must in fact lead the way for all Americans, out of this dusky wilderness of selfishness and materialism, toward what I call a new “culture of character.” For all Americans need a rejuvenated culture, if we are all to enjoy healthy, fulfilled lives. And all Americans must tremble before His timeless and unyielding judgment on those nations that neglect the things of the spirit, to immerse themselves in the things of the flesh.

Is this not asking much of our community—not only to seek, but to lead the way to, a new culture of character? Indeed it is. But this would not be the first time our community has served as the conscience of this nation.

This would not be the first time that our community has spoken the discomfiting truth, and held up the demanding ideal, to an American society that had lost its bearings in the pursuit of the pleasures and the riches of this world.

Once we labored in bondage to fill the coffers of the slavemasters of the South. But then we reminded America that she had promised freedom to all, irrespective of race, sex, or creed. We recalled America to her better self.

Once we rode in the baggage cars, and in the back of the bus. But then we reminded America that she had promised equality to all, and that segregation was a denial of that promise. We recalled America to her better self.

So today, let us remind America and her ailing culture that character is not contemptible, but that it is in fact the only path by which the peoples of this land have worked their way out of poverty and oppression—it is the only path to human fulfillment and happiness. Let us once again recall America to her better self.

Let us pledge ourselves today to work unceasingly toward a new culture of character—both for our own community, and for all Americans. Nothing less is demanded of us by the tradition of Tuskegee, and of Booker T. Washington.

Thank you, and God bless you.