Just more than 25 years ago, on August 22, 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) into law. PRWORA implemented major changes to American welfare policy, replacing the old Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program with a new Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program and granting states much-greater latitude in administering it.

PRWORA both helped Clinton fulfill his 1992 campaign promise to “end welfare as we know it” and was a linchpin of the “Contract with America” that helped Republicans gain full control of Congress in 1994. Congress had passed two versions of welfare reform before Clinton agreed to PRWORA’s provisions.

The policy foundation for PRWORA was laid by state governors who had been seeking, and were granted by the Clinton administration, waivers from the previous system’s rules and requirements. Most of these reform-oriented governors were Republican, Wisconsin’s Tommy Thompson perhaps foremost among them.

The pathbreaking “Wisconsin Works” welfare-reform program, signed by Gov. Thompson in April 1996, required recipients of increased government benefits to seek work and time-limited some benefits, among other things. With others, Jason Turner helped formulate the “W-2” plan, as it’s called. Like PRWORA, W-2 had attracted bi-partisan support in the legislature on its way to enactment.

Milwaukee’s Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, where I used to work, supported much research on welfare policy and related demonstration projects, locally and nationally, throughout the late 1980s into the early 2000s. Historically, Bradley gets much credit, or blame, for the role it played in helping to further the cause of school choice, but that which it did for work-based welfare reform is likely at least as successful, if not more so.

In addition to working for Gov. Thompson, Turner has worked with some reform organizations supported by Bradley. Before his Dairy State days, he worked in top welfare jobs for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. After his cheesehead chapter, he ran New York City’s huge Human Resources Administration. He is now executive director of the nonprofit Secretaries’ Innovation Group (SIG), a membership organization of state human-service and workforce-development secretaries created and supported by Bradley.

Turner keenly understands, well, many things—including the dignity of work, the interplay of publicly and privately funded research and policy development, the challenges of public-policy implementation, and the opportunities for private philanthropy to uphold that dignity, better that development, and improve that implementation if, when, and where possible.

He was kind enough to engage in Q&A by e-mail with me earlier this month. In the first of two parts of the exchange, we cover the circumstances surrounding the reforms’ passage and the effects of their implementation.

In the second part below, Turner addresses philanthropy and welfare reform, SIG, and application of the reform concepts internationally.

***

Hartmann: In Wisconsin and nationally, the Bradley Foundation often gets credit/blame for its role in helping lay the intellectual foundation for school choice, but welfare reform might’ve been as big or bigger a successful policy reform. Do you agree?

Turner: I would say the two are parallel on the unbelievable positive side of successful reforms. Milwaukee is the only big city that had a pro-choice school board and Bradley worked with others in tandem on that incredible success as just one example from the period.

Hartmann: Why the different level of attention given to the two issues? Is it because there’s not equivalent of the teachers’ union in the welfare-reform context?

Turner: I would hardly say the welfare reform in Wisconsin lacked attention! It was national news, and even had an effect internationally.

Hartmann: How would you describe that which Bradley did to lay the foundation for welfare reform in Wisconsin?

Turner: Before I arrived in Wisconsin, Bradley-supported work had been relied upon by Thompson and the administration on the problem of welfare as an institution, generating intellectual support for variations of the waiver reforms—the negative impacts of welfare on family functioning, for example. The Learnfare waiver in particular had national purchase.

During the 1990,s Bradley was funding local programs of success and the state staff visited these with Bill Schambra for reform ideas related to family and economic development. Bradley funded important papers, book authors, and visiting intellectuals in which learning went in two directions.

The usual way conservative reforms are stopped before they get started is having the Left define what kind of thinking is out of bounds. Bradley precluded this through its work and in fact the liberal Institute for Research on Poverty (IRP) at the University of Wisconsin played no role of any kind in the resulting intellectual or practical work in the W-2 development.

Welfare author Larry Mead said this: “It is remarkable that the IRP had nothing to do with W-2. The UW president and dean should have been up in arms over this embarrassment and questioned why. Some people should have been fired.”

Hartmann: Then, nationally?

Turner: When Wisconsin became the center point for state reforms, Bradley was the central agent of communication to and influence on the larger intellectual community, as opposed to merely the political context.

Hartmann: There were other, much less conservative, grantmakers in on “the action,” too, right?

Turner: Yes, other grantmakers were involved in the issue, but I never remember even one who staked out and funded work that became so central to the national discussion at the time.

Hartmann: In general, could/would/should philanthropy be able to do the same or similar things again in this context?

Turner: Bradley is unusual in that it funds and takes positions on conservative issues that make it far more influential (of course, many take positions on the Left, e.g. Ford). By having its intellectual foundation well known, Bradley attracts some of the most-capable intellectual and practical policy people to its stable.

Hartmann: Would this be harder or easier to do than in the (less ideologically polarized) late ’80s and early ’90s?

Turner: It is harder, now but sometimes being first is the most important.

Hartmann: Tell me about the Secretaries’ Innovation Group (SIG).

Turner: The usual breakdown in advancement of public policy is to focus on the intellectual side (research and books) or the implementation side (improvements to programs). SIG sees its role as taking conservative research and ideas, explaining them, and then showing the secretaries how to effectively implement. No other organization does this or can accomplish the merger of conservative philosophy and program execution as well as SIG does.

Second, SIG’s members are at the summit of leadership and precisely the ones who can take action when an idea is proposed by one of the presenters or by another member during discussion. They needn’t persuade anyone else and the money is always there.

Hartmann: When did it start?

Turner: 2012.

Hartmann: Why?

Turner: It was just after the 2010, when many new governors were interested in pursuing the same types of reforms in which we are.

Hartmann: How many members?

Turner: We have 18 states, but there is always turnover.

Hartmann: Any real policy innovators among them who might be particularly worth noting?

Turner: Some of the most innovative have moved on and carried their knowledge partly obtained via SIG membership to their new roles. The role SIG plays is to help new secretaries start with a book of tried and true ideas and help with implementation.

Hartmann: What are the benefits of being a member?

Turner: Of all the benefits, members see the most valuable as interacting with other secretaries in private settings and learning from each other.

Hartmann: What’s its budget?

Turner: $630K.

Hartmann: With whom else does it work?

Turner: We work with the American Enterprise Institute, The Heritage Foundation, and other state think tanks via the State Policy Network, among others.

Hartmann: On what issues is it concentrating specifically now?

Turner: Last year, we focused on COVID and related issues, and unemployment-insurance fraud. This year, we’re looking at a much-broader set of issues—additionally including misused poverty statistics, marijuana and opioids, high-school apprenticeships, foster care, child-welfare lawsuits, and food stamps.

Hartmann: Are there other groups like it?

Turner: The Foundation for Government Accountability does very good policy work aimed at state legislators. They do not do the same thing SIG does, but we trade info.

Hartmann: You mentioned some international applications of the thinking behind work-based welfare reform. Got any examples?

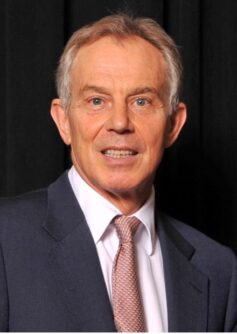

Turner: First, Tony Blair had just become British Prime Minister when I was the welfare commissioner in New York City. I wrote a piece for the think tank Policy Exchange about the Wisconsin reforms. Blair’s Minister for Work and Pensions, Lord David Freud, had himself recently written a pro- reform piece in anticipation of the incoming government with the remit “think the unthinkable.”

[caption id="attachment_76821" align="alignnone" width="237"] Blair (Wikimedia Commons)[/caption]

Blair (Wikimedia Commons)[/caption]

Freud took the Wisconsin concept from Policy Exchange and sent a team to New York, along with KPMG, to learn about the new pay-for-performance system as they were developing their new Work Programme. What they most liked and adopted was that our system had a marketplace of vendors who competed to run the work programs with payment only for results. Their resulting Work Programme replicated these welfare market-vendor competition concepts, which are still in place there to this day.

Second, the Minister-President of the German state of Hesse learned of Wisconsin through his chief policy advisor and began to implement what they called “full engagement,” or the W-2 requirement that all beneficiaries must participate in work search and meet other requirements. He then took this W-2 concept to then-Christian Democrat party leader Angela Merkel.

I testified on W-2 before the Bundestag. Merkel made Wisconsin reforms the centerpiece of her party platform in 2004, promising the electorate to reform their lethargic unemployment system, which Germany did.

Third, W-2 was implemented almost intact in 17% of Israel between 2005 and 2010. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert put together what was formally known as the MeHaLev (“From the Heart”) plan and colloquially known as the Wisconsin Plan. It came about over a two-year planning period after a W-2 Milwaukee vendor (Julia Taylor, then executive director of YWorks) explained how it works on a visit to the country

The concept was picked up by the staff of then-Treasury Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and after further development by me and my consulting team, it was voted out in the Knesset as a four-city pilot, including in Jerusalem. The plan was spectacularly successful at achieving its objectives of employment and reduction of dependency using four vendors, one American (Maximus, which was also in Milwaukee), two British, and one Dutch. It was slated by Prime Minister Netanyahu to become national after the five-year pilot was concluded, but the public-employee union was beside itself with alarm and was able to kill its expansion in committee.

Hartmann: Thanks so much, Jason.

Turner: Thank you, Mike.