Inspired by benefits he enjoyed from the library, Andrew Carnegie funded the creation of over 2,500 libraries around the world. Where are they now?

Andrew Carnegie is well remembered as a gilded age industrialist who directed most of his wealth toward philanthropic causes, many of which still bear his name to this day. There is an endowed foundation named for him, Carnegie Hall still functions as a premier concert venue, Carnegie Mellon University is a well-respected research institution, Carnegie Medals are still awarded to people deemed heroes, and numerous other Carnegie-branded philanthropic initiatives still exist and likely will for a very long time.

But one of Carnegie’s philanthropic efforts—possibly the one he loved the most—appears to have a more complicated record of success with an even more uncertain future.

At age seventeen, Carnegie worked in a textile mill. He was determined to make a better life for himself, but he could not afford the $2 subscription for a local library that was available only to apprentices. He boldly sent a letter to the library administrator asking for free access. After being told no, he published a letter to the editor in the Pittsburgh Dispatch and was soon after informed by the administrator that he could use the library. Carnegie later in life claimed that the “treasures of the world which books contain were opened to me at the right moment.” It is no wonder why Carnegie wanted to expand library access to the masses.

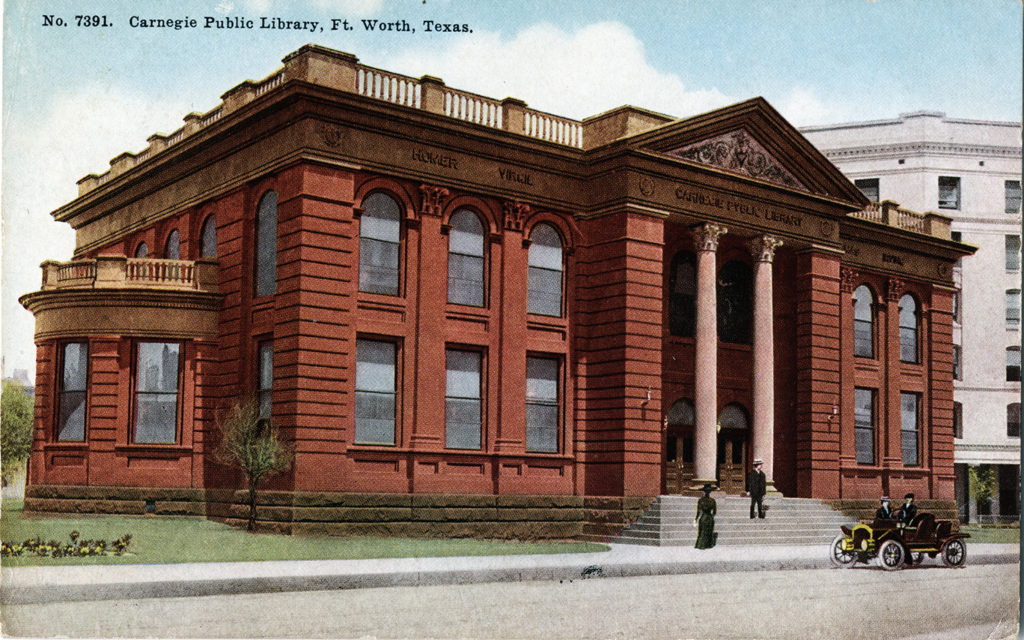

Carnegie began awarding library construction grants to towns in the 1880s. First to Dunfermline Scotland, his birthplace, and then to towns in Pennsylvania. He gradually expanded and helped fund over 2,500 libraries around the world, including nearly 1,700 across the United States in small towns and large cities, plus nearly 100 more at universities. Carnegie libraries, not always named after him, were approved by Carnegie’s personal secretary, James Bertram. Awards were given to towns that had land available, promised to fund the operations of the library with public funding, and provided free access to all. Adjusted for inflation, Carnegie spent over a billion dollars on American public libraries alone.

In Carnegie’s The Gospel of Wealth, he proclaimed that “establish[ing] a free library in any community that is willing to maintain and develop it” was the best way to spend money. In his mind, every town needed a public library that could make knowledge available for free and serve as a meeting place and forum for discussion. While no particular style of architecture was ever required, many of the libraries were built in styles such as Italian Renaissance and Beaux-Arts. Nearly a century since new Carnegie libraries were built, the ones that remain today possess an aesthetic integrity that might remind us of an America where people from all walks of life visited their local libraries easily and frequently without the obstacles of sprawl that has many of us isolated in subdivisions.

So, what has become of Carnegie’s libraries, and what is their future? Of the approximately 1,700 libraries that Carnegie helped fund in American towns and cities, about 800 are still in use as public libraries. Close to 300 have been razed or destroyed, and hundreds more have been repurposed as museums, local government administrative offices, or rezoned and sold to private owners to find new purposes as private residences, law offices, and restaurants.

Two historic Carnegie libraries near me in South Bend, Indiana have quite interesting evolutions. The Old Mishawaka Library in Mishawaka, Indiana was built in 1916, but by the 1970s was replaced by newer library buildings and converted for private use. Just a few years ago, the site was renovated for restaurant use and is now a Latin Grill that has kept the second floor stocked with shelves full of books, making itself a unique space for special events. In a similar fashion, the Carnegie-built library in nearby Niles Michigan was just recently sold to a couple for $100. After being closed for more than fifty years, their plans are to turn the venue into a comedy club.

Photo of interior of Old Mishawaka Carnegie Library, now Jesús Latin Grill

With less than half of Carnegie’s American public libraries still operating as libraries, one must ask the question of whether or not his philanthropic investment was a wise one. Of course, that largely depends on his motivation to construct the libraries in the first place. If he merely wanted to be known as the benefactor-in-chief of American libraries during his own lifetime, then he certainly achieved his goal. Mark Twain wrote, “Mr. Carnegie never gives away money with any other object in view than the purchase of fame.”

If Carrnegie funded these libraries hoping they would serve their intended purposes for centuries, then his record is less impressive. Whatever one’s opinion on Carnegie and the Gilded Age philanthropists in general, one must acknowledge that Carnegie built some beautiful buildings that no doubt inspired more people than we will ever truly be able to count. Those buildings offered quiet places and refuge for people seeking knowledge, including many who had no such access before.

What becomes of the remaining Carnegie libraries in the twenty-first century will be of serious historic significance. Hopefully many remain functioning libraries, and hopefully, the ones that are converted to other purposes are done tastefully while acknowledging the philanthropy of the past.

So glad to be more informed about Carnegie libraries. I have long prized this public legacy and have great respect for Carnegie’s persistent support of free public libraries. I’ve enjoyed spending time in a number of these older libraries and have found that they’re prized where they’re still in use. I see libraries as a great equalizer, a truly worthy public institution, giving access to ideas and information to all. Where I live, our libraries are actively used. I love to be there and consider myself to be in good company even if I never speak to another patron. Thank you — I’ll share this article.

I think it’s worth mentioning that Carnegie’s library legacy includes far more than buildings–he changed the status quo! Free libraries are now the norm, not the exception, all across America. Although your local community library may not be in a Carnegie building, it is free and open to all. And as I’ve seen from experience, even a community library sandwiched in a shopping strip can be an oasis of calm and knowledge in the midst of our hectic world.

Thanks, John, for the fascinating summary of an American legacy that left its impact in the most concrete (and brick and marble) way possible. In my hometown of Three Rivers, Michigan, we have a former Carnegie library that’s been used as a successful community art center for 30+ years. My mother once worked there as a librarian, and it was a wonderful place to read after school, amid the towering book stacks and vast expanse of amber-hued wooden floors and tables. While it’s sad that so many Carnegie libraries have been razed and repurposed for less noble means, but we can hardly fault him for that. Carnegie provided the funds, and it was for communities to determine the libraries’ destiny. As for Mark Twain’s comment that Carnegie only sought to “purchase fame”? We could say the same thing about any book that Twain wrote. (Twain’s ego, if not his net worth, may have rivaled any golden age philanthropist). Further, while naming rights for buildings can seem petty and gratuitous, they don’t diminish the value of any library, exhibit hall, endowed professorship or college program that they make possible. As beautiful works of architecture, Carnegie’s buildings continue to enrich the public square, regardless if they’re public or private property. And, it’s great to hear that in Niles, that will soon include a comedy club!