David M. Rubenstein “wants to write at least two more” books, including “one about his views of patriotic philanthropy,” reports The Wall Street Journal’s Chip Cutter in a late-August article on Rubenstein. One would certainly look forward to a Rubenstein book about “patriotic philanthropy” in any case. But one might do so even more now, given this Summer’s disheartening treatment of American monuments and memory, which patriotic philanthropy generally seeks to restore and strengthen, respectively.

In 1987, Rubenstein co-founded the Carlyle Group, a highly successful private investment firm currently managing more than $200 billion in 32 offices around the world. His reported net worth comfortably exceeds $3 billion. He also hosts the always-engaging David Rubenstein Show: Peer-to-Peer Conversations on Bloomberg TV and PBS. He is a pillar of the country’s financial, philanthropic, and media establishments.

Rubenstein serves on the boards of very many prestigious institutions. He chairs the Library of Congress’ James Madison Council, for example, which helps fund important Library projects related to American history and Western identity.

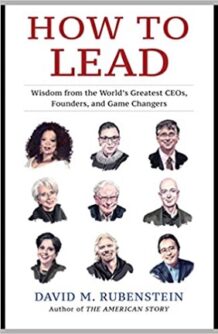

The 71-year-old Rubenstein, a onetime Carter-administration official, briefly overviews his notion and practice of “patriotic philanthropy” in the introduction to his just-released book How to Lead: Wisdom from the World’s Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game Changers. The book is an outgrowth of and includes partial transcripts from some of his interviews for the David Rubenstein Show.

“In the realm of philanthropy, I was one of the original signers of the Giving Pledge (created by Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett),” Rubenstein writes in How to Lead,

and essentially fostered the concept of “patriotic philanthropy,” i.e. taking actions to remind people of the history and heritage of our country: buying Magna Carta and providing it to the National Archives; preserving rare copies of the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation; helping to repair the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, the Jefferson Memorial, Monticello, Montpelier, and the Iwo Jima Memorial.

The history and heritage of our country have come under attack. Any book-length explanation and defense of Rubenstein’s once-uncontroversial efforts to philanthropically support that history and heritage would be well-warranted.

In How to Lead, Rubenstein says he has tried “to pursue actions that I hoped would lead others to follow” him in his philanthropy. He amicably discusses philanthropy in its excerpted conversations with each of the Gates and wildly wealthy investment managers Ken Griffin and Robert F. Smith. A tome on Rubenstein-style “patriotic philanthropy” could perhaps help them and other respected establishment figures like them to follow, peer to peer.

Also in late August, the District of Columbia Facilities and Commemorative Expressions (DCFACES) working group put formal text to our difficult American Summer’s toppling and spray-painting of so many statues and monuments. The working group recommends that the city’s historical statues, monuments, and schools be “removed, renamed, or contextualized” in certain cases.

These specifically include the Rubenstein-repaired Washington Monument, along with the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials, of course, among many others. (Recall the jarring images of National Guard soldiers standing in defense of the Lincoln Memorial on an early-June night.)

“[W]e believe strongly that all District of Columbia owned public spaces, facilities and commemorative works should only honor those individuals who exemplified those values such as equity, opportunity and diversity that DC residents hold dear,” according to the DFACES chairs.

What does Rubenstein think about this?

An answer might be gleaned from an op-ed he penned for the July 4 holiday this past Summer. The fact that Thomas Jefferson, “with his obvious flaws, which were shared by many Founding Fathers, unknowingly wrote the words that have become the creed of this country should not detract from the Declaration and its relevance to today’s challenges,” Rubenstein writes.

“We should take comfort in the progress made since 1776 toward the creed; we should not take comfort that enough progress has been made toward the creed,” he continues. “And we should resolve that in celebrating the Fourth of July and the Declaration, we are really celebrating where the country should be heading—where everyone can feel and be equal in rights and opportunities—and hopefully will arrive someday soon.”

How is Rubenstein’s “patriotic philanthropy” practiced in the meantime? Given the radicals’ reigning reaction against American monuments and memory, is it really even possible? Why would or should one even try doing it?

A next book by Rubenstein on "patriotic philanthropy," if and when forthcoming, would likely be quite a valuable contribution to public discourse, and another good example of how to lead in philanthropy.