The power of “the progressive liberal vision of American public life” reflected so overwhelmingly in its popular culture “derives above all from the fact that it bespeaks a powerful human story, one with particular resonance in the American soul,” according to Michael S. Joyce, then president of The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation. In this story, “the average citizen, wishing only to run his own affairs according to his own lights, is ignored, manipulated, and disempowered by the entrenched special interests,” as Joyce told it. When “at last he’s fed up with the abuse, he rises in righteous rebellion and seizes control of his own affairs again, in a grand renewal of the American ideal of citizenship.

“Such has been the theme of a thousand familiar novels, movies, and TV specials, because this is the great American story,” he observed. Conservatives dismiss it at their peril, remaining “on the defensive, merely reacting, forever playing catch-up. … It’s time for conservatism to ponder anew the great American story—for a critical shift is occurring in the American scene today,” he suggested in his “Remarks to the National Review Institute Conference,” in January 1993. “To put it bluntly, we are no longer on the wrong side of the American story. Liberalism is.” (All emphases in original.)

For evidence of the noted transformation, among other things, Joyce interestingly cited “massive, palpable discontent with all major governing institutions” and, “the immense popularity of Ross Perot’s” (then-?)radical populism. Interestingly, and presciently. “The message, I believe, is clear: Americans are sick and tired of being treated as if they’re incompetent to run their own affairs.”

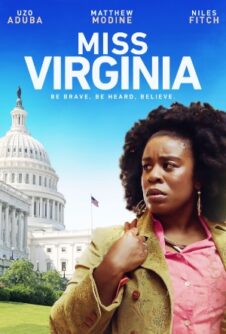

Virginia Walden Ford’s is the great American story, she’s on the right side of it, and it’s dramatically well-told in the new movie Miss Virginia. In the movie, Emmy winner Uzo Aduba plays Ford as she—sick and tired of being treated as if she’s incompetent to choose her own child’s school—rises in righteous rebellion and seizes control of her own affairs again by fighting for school choice in Washington, D.C., in a grand renewal of the American ideal of citizenship.

As also told in her forthcoming autobiography School Choice: A Legacy to Keep, “Miss Virginia” was an already-struggling single mother from a low-income neighborhood who decided to take on yet another struggle—to seek another option for the education of her teen boy. She was highly dissatisfied with the public school he was assigned to attend. She very much feared that he might be on his way to a life of drug dealing and all of that which too often follows. She couldn’t afford the tuition at other, nearby private schools, however.

Overcoming several obstacles, including her own fear of public speaking and the powerful educational establishment, Ford and the D.C. Parents for School Choice group she formed in the late 1990s sought to secure educational opportunity for her child, at another school, of her choosing. It was a story known to Bradley, which supported similar groups in Milwaukee and elsewhere; it helped fund D.C. Parents for School Choice, too.

As Miss Virginia shows, the determined Ford inspiringly rallied other parents, community leaders, and policymakers to act on behalf of children like hers, who needed a hand for their shot at the American dream. Inspiringly, and ultimately successfully. She was accused of being a political pawn.

Launched in 2004, the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program is the only private choice program in the country created by Congress. As part of the program, in Spring 2019, the parents of 1,645 participating students were able to redeem vouchers worth $9,531 at 46 participating schools, according to EdChoice. It also boosted funding for traditional public schools and public charter schools.

Produced by the Moving Picture Institute, which is also supported by Bradley, the movie is being widely praised. Production and distribution of the film itself has been and is being supported by the Searle Freedom Trust, the Gleason Family Foundation, and the Diana Davis Spencer Foundation, among others. The movie can be accessed for viewing here, and the Moving Picture Institute is conducting a grassroots community-screening tour for it, and the story it tells.

“Americans are clearly willing and eager to seize control of their daily lives again—to make critical life choices for themselves, based on their own common sense and folk wisdom,” according to Joyce in ’93. They are ready “to assume once again the status of proud, independent, self-governing citizens intended for them by the Founders, and denied them by today’s social-service providers and bureaucracies.

“This should, of course, sound familiar,” he continued.

It’s the great American story being played out once again. But this time, the leading roles are reversed. The entrenched, corrupt special interests are the towering bureaucracies of liberalism, not the corporations. And this time—if only we have the eyes to see and the imagination to seize the opportunity presented us—conservatism can stand with the average citizen, against the intrusive institutions of liberalism that seek to dominate and manipulate his life.

Joyce exhorted conservatives “to understand this dramatic role reversal in the great American story”—basically, to look around, to listen, and to learn. Good advice for philanthropy always, including in this context. “For all about us are the dramatic, compelling tales and pictures—begging to be written, filmed, and painted—of courageous individuals struggling to run their own lives according to their own lights, and yet who are ignored or abused by powerful social structures jealous of their own prerogatives.”

He listed some specific examples: like Miss Virginia, the

impoverished mother who struggles against the public-school bureaucracy to put her child in a private school where discipline and values prevail; the street vendor who battles licensing and zoning boards in order to make an honest living; the middle class-family that braves the ridicule of the social-service professionals in order to challenge the distribution of condoms in school; the public-housing tenant who seeks to govern his own project, in spite of an enervating maze of regulation ….

One could perhaps add some new ones now. Among them: workers who don’t want to join a union and have to struggle against those would coerce them to do so; union members themselves who are offended by their union’s political positions and corruption, and who battle for reform; people who are prevented from freely voicing their opinions and participating in public discourse on college campuses and elsewhere, and who challenge the restrictions imposed upon them; and cakemakers and videographers who don’t want to be forced to approve beliefs they don’t share on moral grounds, and who object.

“[L]et us make their stories,” Joyce said, “our stories.” If you have the time, maybe read his full remarks, which are part of this Giving Review collection. If you can, definitely see Miss Virginia and its telling of Ford’s story, our American story.