History is littered with examples of philanthropists who failed to secure the legacy they intended.

Anyone who has ever given a ten-year-old an allowance knows how hard it is to do good by giving money away. Philanthropic giving is still more difficult to do well, even when you’re around to watch over it. Once you’re gone and others control your legacy, your odds of failure are even higher.

History is littered with examples of philanthropists who failed to secure the legacy they intended. My organization, the Capital Research Center (CRC), has just published the fourth edition of our book How Great Philanthropists Failed and How You Can Succeed at Protecting Your Legacy, by CRC senior fellow Martin Morse Wooster. It details the sordid history of charitable giving gone awry in the past—and how wiser givers today can plan ahead to avoid those disasters.

Here are a few of the horror stories where a donor’s intent was betrayed.

Radical Takeover

The story of John D. Rockefeller’s rise from bookkeeper to oil baron is famous. Less well-known, though, is his failure to plan how his immense fortune would be spent in the future. Today, the billions that Rockefeller created through his entrepreneurial genius are in the hands of treacherous elites, who use that wealth to attack the very system that generated it.

What went wrong?

Since his youth, Wooster explains in his book, Rockefeller was always extraordinarily generous with his money, giving gifts between $50 and $500 early in his philanthropic career. Later in life, he set his sights on creating a foundation to disburse his money “to the promotion of human well-being”—but left the specifics of that broad mission undefined.

When Rockefeller, a religious conservative, relinquished control of his trust in 1916, he left power in the hands of unscrupulous advisers—nearly all of whom were left of center. They quickly removed any limits to what the money could be spent on, while his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., made little effort to ensure the family stayed in control of its fortune. By the time the oil tycoon died in 1937, the foundation he built to help promote education, upward mobility, and public health was in the hands of the very radicals he deplored.

Donor Intent Buried Alive

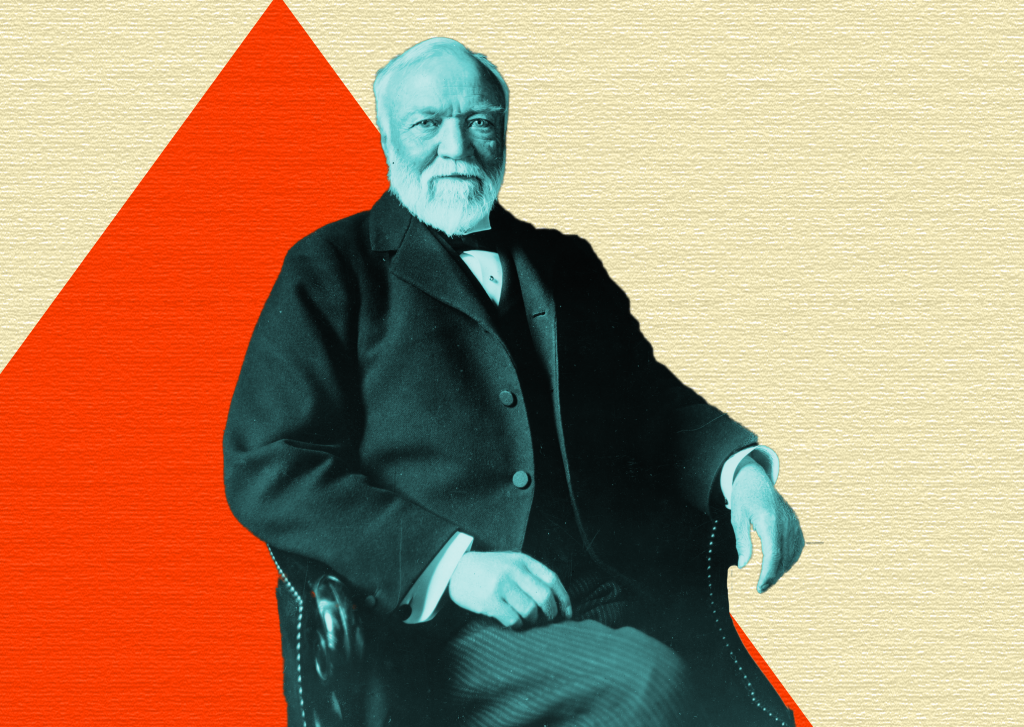

Another titan of industry, Andrew Carnegie, suffered a similar fate.

The Scottish-born Carnegie built his fortune from very humble beginnings thanks to a free market system he greatly admired. As he built a vast steel empire, he prided himself on helping to create a prosperous America for others.

Carnegie had a similarly entrepreneurial view of philanthropy, saying that “the main consideration” of charity “should be to help those who cannot help themselves [but] who desire to improve” their lives. The numerous hospitals, libraries, colleges, parks, and concert halls which bear his name are testament to his admirable generosity.

So where did Carnegie go wrong?

In 1911 when he created his largest philanthropy, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the steel magnate gave it one instruction: provide pensions for the widows of former U.S. presidents. Otherwise he ceded control of the foundation to the judgment of his trustees.

Carnegie’s intent for his money was overruled almost immediately. The presidential pensions were almost all halted, and his plan to build libraries across the nation met an unhappy end. The library project was dear to his heart, because when young, Carnegie gained most of his education via a wealthy man’s library that was open to the public. When he became wealthy himself, in part thanks to that library, Carnegie wished to seed similar libraries throughout America to help poor but enterprising youth rise to success.

Yet the progressive elites who ran Carnegie’s foundation first twisted the library program’s design, then cancelled it altogether—while Carnegie was still alive.

Courting Disaster

You don’t have to be among the world’s wealthiest entrepreneurs to have this happen to your legacy.

Consider the not-so-famous Carl J. Herzog Foundation, which made a grant to a university to endow nursing scholarships. A few years later, the university closed its nursing school and just tossed the money into its general endowment. The foundation sued, asking that the original gift either be returned or transferred to a local community foundation that would administer nursing scholarships. The Connecticut Supreme Court ruled in favor of the university because the foundation didn’t include in its gift a reversionary clause that stated the money should be returned if the university couldn’t use it for its original purpose.

Even donors with modest philanthropic goals should consider the best way to protect their intent.

In the most recent issue of the New York Times Magazine, an important question about honoring donor intent arose in a letter to The Ethicist column: Should a son honor his deceased father’s wishes by completing donations to the National Rifle Association, Hillsdale College, and election campaigns for Senator Ted Cruz? These causes didn’t align with the son’s own worldview, but his father made careful notes indicating that he wished the donations to be made, and the son had been handed his father’s checkbook on the promise he would pay the elder man’s bills and honor his philanthropic donations.

The conflicted letter-writer seemed to know the answer, even as he asked the question. He feels uncomfortable about this omission and quotes his late father’s maxim: “If you lie, you cheat, and if you cheat, you steal.”

The Ethicist columnist, Yale professor Kwame Anthony Appiah, gives an absolutely correct answer: It is unethical to violate a donor’s own intentions for his philanthropy. The son will do well to uphold the philanthropic wishes of his father, settle the remaining business, and then take solace in honoring his father well.

Alas, Professor Appiah advice goes mostly unheeded today, which means donors must take steps to ensure that their wishes are clear and that the necessary precautions are in place to have their philanthropic vision carried out.

Rising Above The Demons

So what can givers today do to secure their legacy?

Here are a few principles to keep in mind:

- Carefully define the mission of your philanthropic giving, whatever vehicle you use (bequests, donor-advised fund, trust, or foundation).

- Choose trustees and staff who share your principles completely.

- Give generously while living, so you learn which grantees best fit your vision.

- And if you start a foundation or donor-advised fund, strongly consider having a sunset provision that will spend-out your legacy at a set time.

And as Wooster notes, above all, “be wary of anyone who argues that the ideas, principles, and passions of donors are unimportant.”

Photo credit: AK Rockefeller via Visualhunt.com / CC BY 2.0

2 thoughts on “Donor intent gone wrong”