Steven Hayward’s new biography details M. Stanton Evans’s life and his role in the modern conservative movement.

I have known Steven F. Hayward for over 40 years, and I continue to enjoy his work. Today I commend to you his latest, M. Stanton Evans: Conservative Wit, Apostle of Freedom. There are two reasons why you should read this book.

First, Hayward is a very good historian and a fine writer. His previous book, Patriotism Is Not Enough, an account of the intellectual battles between Harry Jaffa and Walter Berns, addresses deep issues about the nature and purpose of government. And it is one of the most enjoyable books of political theory ever written. His earlier two-volume history, The Age of Reagan, is a book of traditional narrative history about America from the election of Lyndon Johnson to the end of Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

This new biography of M. Stanton Evans is also well worth reading. It isn’t just a political life, for Evans had a great deal to do with the nonprofit world. He was involved in creating two nonprofits, and he gave one of the most important figures in conservative philanthropy her start.

Evans was one of the organizers of the American Conservative Union (ACU), which began operations in 1964. From 1971 to 1977 he served as ACU chairman. In 1974, the ACU created the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), and Evans headed the first three CPACs.

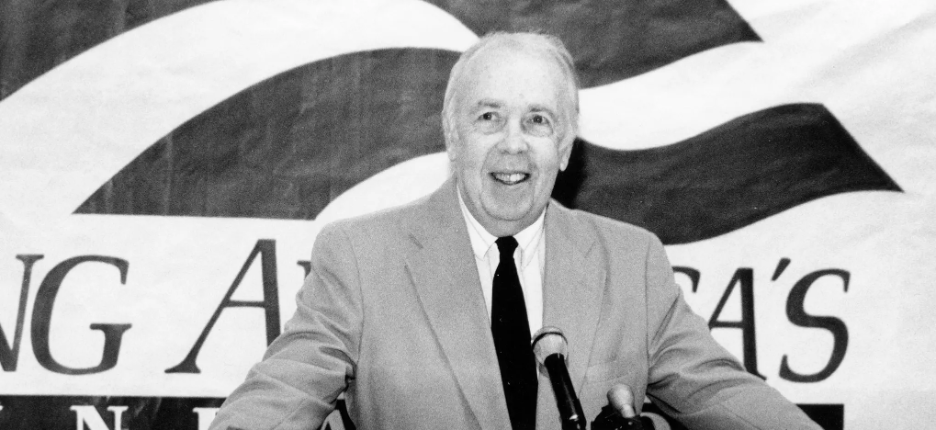

In 1972, during his tenure as ACU chair, Evans created the Education and Research Institute (ERI) as a think tank affiliated with the ACU. The most important project of ACU and ERI was the creation of the National Journalism Center, which began operations in 1977 and in 2002 became a division of Young America’s Foundation.

A great many journalists got their start at the NJC, including John Fund, Greg Gutfeld, William McGurn, and people you wouldn’t expect, including Terry Moran of ABC News, Greg Myre of NPR, and author Malcolm Gladwell. At least one foundation president, John Hood of the John William Pope Foundation, is a National Journalism Center alumnus.

But from the viewpoint of philanthropy, the most important National Journalism Center alumnus was Whitney Ball. Before she created DonorsTrust, and before she was the head of the Philanthropy Roundtable, Ball was the director of development for the National Journalism Center, where she began her dealings with conservative foundations. She also organized a tribute to Evans in 2011, which I attended, and which was very enjoyable.

Ball is not mentioned in Hayward’s book, and she should be; she’s probably as significant a figure as any journalist who went through the NJC’s programs.

Evans’s final contribution to philanthropy was his philosophy of “fusionism” in philanthropy. Evans’s philanthropic fusionism is a synthesis of conservatism and libertarianism. Consider the question of what the government is meant to do. For the conservative, the state is designed to promote virtue; for the libertarian, it is to allow people to be free. For the fusionist, government should promote freedom to encourage people to live virtuous lives.

When dealing with civil society, both conservatives and libertarians have answers that are partially right and partially flawed. The libertarian is correct when he wants to shrink the state. But lower taxes and less regulation do not necessarily lead to people living virtuous lives. The conservative—and, today, the national conservative—hopes in the ability of the state to encourage (or force) people to be decent and just.

The fusionist philanthropist recognizes that lower taxes and limited government create more opportunities for people to be generous, but do not automatically cause people to be philanthropic. “The ends of politics cannot be politically derived,” Evans told the Philadelphia Society in 1977, “They must come from a realm of affirmation beyond the legislature and the precinct.”

Similarly, the impulse to philanthropy should come from within a donor. There’s been a lifetime of speculation about why Bill Gates created the Gates Foundation but it’s clear that Gates’s turn towards philanthropy—something he began early in his career—was something deeper than merely a concern about reducing his marginal tax rate.

When it comes to fighting philanthropy the fusionist philanthropist recognizes that cause of poverty is often character failings along with a lack of money—which is why the best poverty-fighting organizations, such as rescue missions, address spiritual as well as financial difficulties in the people they shelter and help. These missions save tax dollars—but, more importantly, they save souls. That is why they’re worth supporting.

Hayward, finally, does readers the kindness of including an appendix of Evans’s best jokes and quotes. Evans’s wit was one of his greatest characteristics, as his jokes make clear: “We have two parties and only two,” Evans said. “One is the evil party and the other is the stupid party. I’m very proud to be a member of the stupid party. Occasionally, the two parties get together to do something that’s evil and stupid. That’s called bipartisanship.”

Steven Hayward’s M. Stanton Evans is a sell-written and thoughtful look at one of the leading conservatives of the 20th century.