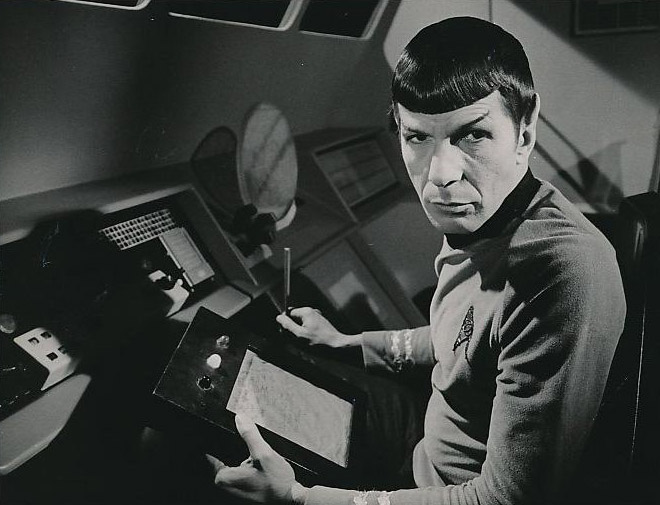

The death of Leonard Nimoy—Mr. Spock—was widely noticed and discussed—even President Obama issued a statement on Nimoy’s death and the character of Mr. Spock.

What was it that people were remembering, and why is Star Trek such enduring phenomenon?

Star Trek has endured much longer than other TV shows that seemed to capture a particular cultural moment but then faded from relevance, such as The Mary Tyler Moore Show, which captured the feminist moment of the 1970s, and Hill Street Blues, which captured changes in working- and middle-class life during the 1980s. Star Trek has gone on for decades: the original show in 1960s, five spin-off television series, and eleven movies to date, with the twelfth movie slated for release this July. Star Trek shows and movies have been in production for just shy of a half-century.

The original show spoke to Cold War anxieties, with its crew that mixed Russians, Chinese, Americans, and others to suggest that the Cold War would be left behind (and it was reassuring that American Captain Kirk was in charge). The year after the Loving v. Virginia case, a kiss between Captain Kirk and Lt. Uhura was only one of the fist times a kiss between an interracial couple appeared on television. But the Cold War is over and, while we are not yet in a post-racial era, America has long moved past the point where an interracial kiss might be controversial programming. These aspects of Star Trek seem as passé as The Mary Tyler Moore Show’s presentation of the novelty of a woman having her own apartment.

The enduring cultural relevance of Star Trek is explained by the fact that Star Trek, and Mr. Spock in particular, expresses a moral stance that has been prevalent over the last several decades—indeed, the last couple centuries.

That moral stance is summed up not in Mr. Spock’s Vulcan greeting “live long and prosper,” but in his Vulcan maxim, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, or the one.”

This maxim has a long history in moral philosophy—indeed, a history all the way back at least to Plato’s Republic, where Socrates asserts that rulers shouldn’t look to the happiness of any part of the community but to the happiness of the whole. The problem, Socrates argues, is that most rulers are guided by their own interests. Only philosophers guided by reason alone can be trusted to look to the happiness of the whole community—hence, Socrates concludes, it is necessary to be ruled by “philosopher-kings.”

I have heard it suggested that Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry borrowed the maxim “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, or the one maxim” from Plato’s Republic. And, even if Roddenberry didn’t do so, there’s an obvious parallel between the rational, emotion-free Mr. Spock and Socrates’ philosopher-kings.

The moral claim that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few returned to prominence in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when it became known as “utilitarianism,” the name given to it by proponents Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. It remains one the most prevalent moral views.

Putting the needs of the many ahead of the needs of the few sounds noble. Indeed, at the climax of the second Star Trek movie, The Wrath of Khan, Mr. Spock cites this maxim as he heroically sacrifices his life to save that of his crewmates.

But what justifies an individual heroic action doesn’t make for a general guide to public policy. Other philosophers—from Aristotle to Karl Popper—have pointed out that the imposition by policy fiat of what’s best for the greater number can run roughshod over the interests and rights of minorities and individuals. Many of the public policy failures of the last half-century are underpinned by the view that what’s best for the greater number can override the interests and rights of the few—and it’s no coincidence that this is the same view embodied for the last half-century in the acclaimed Mr. Spock.

There is no such thing as a “twelfth movie slated for release this July” in the Trek series in this or any other alternate universe.