Dear Intelligent American,

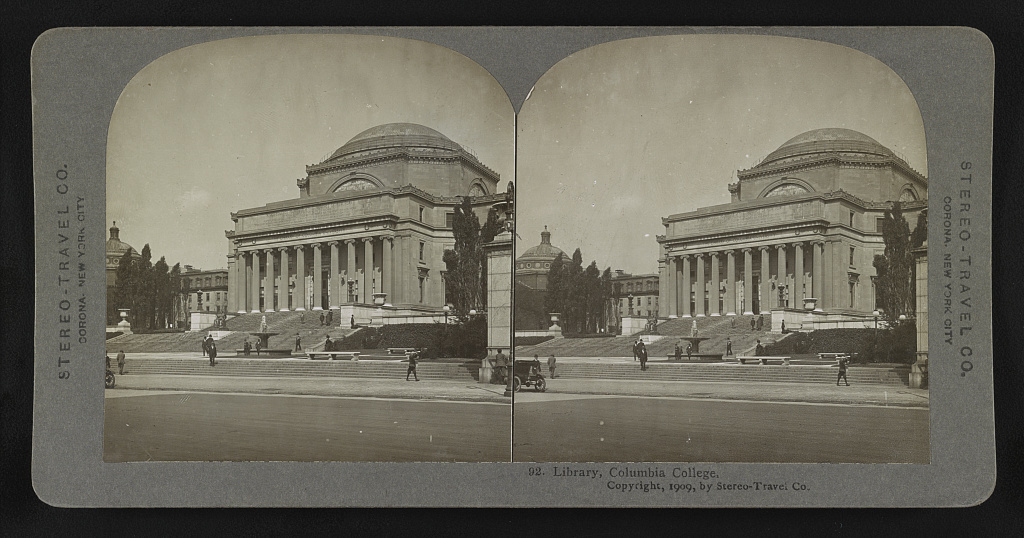

First things first: Happy Passover to our Brothers and Sisters in Abraham. May we wonder how it is being celebrated up in Morningside Heights: Boy oh boy, Columbia University ain’t the place Ike ran, no? More on that below. Right now, let’s focus on 1835.

This space does not make mention enough of Alexis de Tocqueville, a.k.a. ADT, the apostle of “civil society” and biographer extraordinaire, through Democracy in America, of our nation’s exceptionalism, at least the mid-1800s variety. The recent 165th anniversary of his death (April 16th) did not go unnoticed: At the Washington Examiner, Adam Carrington took it as an opportunity to provide us a refresher on the Normandy aristocrat, and his enduring relevance—it can be found here. And here is a dose:

Tocqueville saw democracy at its worst as enforcing an equality that squelched liberty and excellence. Liberty and excellence distinguish persons who have more of it from those who possess less. A certain view of equality, one that demands basically similar results, must curb or even punish anyone who distinguishes him or herself. This mediocrity also led to severe individualism by destroying grounds for community. Destroying this community then led to social and political isolation, a problem that not only hurt human happiness. Political isolation also made people too weak and thus dependent on the government.

Does anyone hear an echo in here? Whether you do or don’t, let us now sally forth into the Valley of Excerpts!

Beaucoup Wisdom Ici!

1. At The American Mind, Richard Samuelson wades into the “Christian nationalism” fracas, and sees the charges of ideologues colliding with Thomas Jefferson. From the piece:

Jefferson was, of course, a fervent believer in the rights of conscience, and a forthright opponent of religious establishments. In his Notes on the State of Virginia he argued that “the rights of conscience we never submitted, we could not submit. We are answerable for them to our God. The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” Having said that, Jefferson did not think religious beliefs were irrelevant to establishing and sustaining a free republic, holding that the republic was dependent upon having a citizenry who believed in God, not gods. Later in the same work, discussing slavery, he declared, “can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever.”

The most logical explanation of the apparent inconsistency between not caring if someone believed in zero or multiple gods, and also believing that the “only firm basis” for our liberties is belief in God, is that it is, per Jefferson, no danger if some Americans believe in no or “twenty gods,” but it is a problem if either belief, or other like beliefs, become common. “The people” in general need to believe that their liberties are the gift of God, not to be violated without his wrath—and His wrath, Jefferson was suggesting, would surely come if Americans did not work to end slavery pronto. If some handful of Americans disagreed, that was nothing to worry about. But if that became common, he suggested, it would likely be a problem. In other words, Jefferson feared that the rights of conscience, and our liberties in general, would not be secure among a people who did not think they are answerable to God for their actions, and who doubted that there is a Creator who ordered nature.

2. More TAM: Fan favorite Daniel J. Mahoney comes to the aid of the often-distorted image and political repackaging of Ronald Reagan. From the piece:

Nor was Reagan an inflexible ideologue, even if he always remained a proud, principled conservative. In a wonderful speech to the Fourth Annual Conservative Political Action Conference on February 6, 1977, he insisted that conservatism had nothing to do with ideology or “ideological purity.” American conservatism is at once “principled” and “free from slavish adherence to abstraction.” When an American conservative defends the market economy “he is merely stating what a careful examination of the real world has told him is the truth.” When a conservative adamantly opposes communist totalitarianism, “he is not theorizing—he is reporting the ugly reality captured so unforgettably in the writings of Alexander Solzhenitsyn.” And when conservatives favor government that is close to the people—and not one that is distant, bureaucratic, and intrusive—they build on the experience and wisdom of our founding fathers who risked their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to save free men and women from “an ideology of empire.”

For the half-populist Reagan, true conservatism must remain rooted in “the common sense and common decency of ordinary men and women.” It has nothing to do with “the kind of ideological fanaticism that has brought horror and destruction to the world.” At the same time, Reagan fully appreciated that common sense must be rekindled and renewed by faith in Divine Providence and a commitment to a “political philosophy” that cherishes families, churches, neighborhoods, and communities—“the institutions that foster and nourish values like concern for others and respect for the rule of law under God,” as he described in his “Evil Empire” speech.

3. More Mahoney: At Law & Liberty, the scholar explains why the great political philosopher Leo Strauss mattered and matters. From the essay:

When I first read Natural Right and History as a graduate student in the early 1980s, I was won over by the mixture of wisdom and spirited solicitude for Western civilization that seemed to mark the book from beginning to end. Strauss pointedly took aim at facile relativism and the thoughtless denial of natural right that were typical of the most influential currents of modern philosophy and social science. Without being openly or obviously religious, he had every confidence that reason could adjudicate between thoughtless hedonism and “spurious enthusiasms” on the one hand, and “the ways of life recommended by Amos or Socrates” on the other. He freely evoked such uplifting and ennobling categories as “eternity” and “transcendence” (even if in a more specifically philosophical idiom) and feared that the abandonment of the quest for the “best regime” and the best way of life would undermine the human capacities to cultivate the soul and “transcend the actual.” Human beings could become too at home in this world, he feared.

Strauss’s respectful but hard-hitting critique of the “fact-value” distinction articulated by the great German social scientist Max Weber allowed me as a young man to more fully appreciate how crucial discerning moral evaluation is to seeing things as they are. Such calibrated moral evaluation is integral to social science (and political philosophy), rightly understood. Among other things, Strauss brilliantly pointed out that, and how, Weber departed from his own theory: “His work would be not merely dull but absolutely meaningless if he did not speak almost constantly of practically all intellectual and moral virtues and vices in the appropriate language, i.e. in the language of praise and blame.” A striking discussion in Natural Right and History observed that “the prohibition against value judgments in social science” would allow one to speak about everything relevant to a concentration camp except the most pertinent thing: “we would not be permitted to speak of cruelty.” Such a methodologically neutered description would turn out to be an unintended, biting satire—a powerful indictment of the social science enterprise founded on it.

4. More L&L: Daniel Miller commences a forum on the recurrent modern phenomenon of revolution. From the essay:

Modernity is the epoch of revolution unbound. Beginning with the overthrow of scholastic authority by the natural philosophers of the Royal Society, and extending to the digital revolution still unfolding today, every modern scientific and cultural project is articulated as a revolutionary overcoming of obsolete methods and paradigms. An identical attitude has defined Western art for more than two centuries. From romanticism to conceptualism, every artistic movement in every artistic medium has announced itself as the revolutionary surpassing of an exhausted tradition.

Modern revolutionary ideology crystalizes a meaning in direct contradiction to its original associations. The classical world grasped the concept of the revolutionary cycle of regimes as the political analogue of the eternal cycles of nature. As Hannah Arendt notes in her 1963 book On Revolutions, the Latin term revolutio is a perfect translation of the Greek term anacyclosis, which was used in astronomy before being employed by Polybius in his famous reflections on the decompositional cycles of government. Revolution today carries the opposite meaning. Revolution no longer refers to a cycle but to a singular event in a rectilinear history in which nothing comparable has happened before and nothing can ever be the same again.

Revolution inaugurates a rupture in the continuum of history itself: all the old laws are suspended; everything is made new. This messianic delusion is recurrent to the revolutionary phenomenon but almost nothing in history is less singular. Despite the invariable rhetoric of the radically groundbreaking, an identical cycle repeats itself endlessly whenever revolution appears. Even the digital revolution has obeyed this trajectory from the naive utopianism of the nineties to the global surveillance state that cradles the planet today. From ancient rebellions to implosions of postmodern cults, the story is always the same because revolution is the opposite of what ideology thinks: not a political or modern phenomenon, but a religious and recurrent phenomenon transposed into modernity as political ideology at the moment when politics became crypto-religious.

5. At the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, Adam Kissel explains that the miraculous education-reform strides made by West Virginia must take hold in the state’s high-ed institutions. From the analysis:

Six-year graduation rates do not restore confidence: WVU’s rate is 58 percent. West Virginia State University’s is 34 percent. And West Virginia is not so different on this measure than other states, such as Louisiana. Huge numbers of students are not able to finish their degrees, but they end up with college debt anyway after years of being outside the full-time workforce, not having developed marketable skills, but having become disconnected from the communities and families they left in order to pursue their college hopes.

This must change. West Virginia substantially over-invests in our over-enrolled four-year public colleges, especially when compared to investments in our career-college system. In West Virginia, you can get a two-year degree to become a power-transmission installer from Pierpont Community and Technical College and be earning $89,000 two years after graduation with only $11,000 in college debt. Or you can get a fine-arts degree from WVU, earn $18,000 per year, and have $27,000 in debt. (These are the extremes, based on cohorts from 2015 and 2016, which are in the sweet spot between the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic chaos.)

The budget that West Virginia’s legislature passed on March 9, 2024, shows $8.6 million for Pierpont (which has dramatically lost market share since 2008) and far north of $100 million for WVU and all its parts. Although funding roughly tracks enrollment, there is room to rebalance and get more students out into the workforce faster. What would it take, for example, to further boost Pierpont’s already increasing two-year completion rate?

6. I Went to a Boxing Match, and a Hockey Game Broke Out: At Comment Magazine, Sean Speer checks out the rink and how it sometimes serves as a ring. From the piece:

Hockey has been violent since its origins. Most hockey historians agree that hockey was created when Europeans brought over their traditional stick-and-ball games to North America in the eighteenth century, which gradually evolved into organized hockey in the nineteenth century. Hockey most likely developed its physicality and violence from European exposure to lacrosse, which was played by Indigenous peoples.

There were apparently fights between players and spectators in the first indoor hockey game in Montreal in March 1875. The first documented fight during a game occurred in 1890 between the Rideau Hall Rebels and the Granite Hockey Club of Toronto. Fighting soon became a common feature of amateur hockey throughout the era and was imported into the professional ranks when the National Hockey League was established in 1917.

In these early days, fighting wasn’t subjected to rules or sanctions, and the physical altercations were often quite dangerous. In 1905, for instance, a twenty-four-year-old French Canadian named Alcide Laurin died after being punched and hit in the head with a stick during a game. Owen “Bud” McCourt, a member of the Federal Hockey League’s Cornwall Royals, was killed two years later when he was attacked by a number of Ottawa Victorias players. Author Ross Bernstein refers to this era as “more like rugby on skates than it was modern hockey.”

The NHL instituted a five-minute penalty for fighting (or “fisticuffs”) in 1922, but the norms and patterns were already set. Fighting would be an ongoing element of the sport for the next several decades. Even star players like Maurice Richard or Gordie Howe were more than capable of taking care of themselves.

7. At First Things, Mark Bauerlein profiles a small community of reclusive Carthusian monks praying in Vermont’s Taconic Mountains. From the reflection:

My hosts take me to a cell, pointing out an empty cabinet installed in the wall to the right of the portal before we go inside. The door to the cabinet is open, and I can see that in the back of the space is a matching door. It’s a delivery system. A meal is brought to the cell in a wooden box. It is set inside the cabinet, the outer door is shut, a buzzer is pressed, and the monk within opens the back door and draws out his food so that no human contact occurs. Everything else he needs is already there: a cot, woodstove, oratory, and a shelf that holds Scripture, the Statutes, and books of the monk’s choice taken from the monastery’s library, which offers theology, history, philosophy, literature, art, tales of the Desert Fathers and the saints, reflections on monasticism (I spotted an entire shelf of Thomas Merton), and lots of “Carthusiana.” The monk may take notes on his reading, but keeping a journal of his life in solitude requires permission. He may share his theological thoughts with others only during a walk the monks take every Monday. Otherwise, the Statutes prohibit all conversation apart from brief exchanges about pressing practical matters. Inside the cell, reading aloud is encouraged—not his own words, but the words of Scripture, and not too loud, either. Firewood is stored in a room below, which each monk must cut and chop himself. A door leads to a private garden attached to the cell, with a fruit tree and vegetables tended by the occupant, and more ten-foot walls separating it from other gardens.

Each cell is one monk’s “desert.” That’s what they call it. It’s cut off from the world and from the rest of the monastery so that it may do its work on the inhabitant. “Go, sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything,” Desert Father Abbot Moses told novices who came to the Egyptian desert in the fourth century. The Statutes require monks to let themselves “be molded by it.” The space we tour is spare and vacant save for utensils for eating and a dozen books: Anchor Bible commentaries, the Statutes, three volumes of Cardinal Newman, and Christopher Dawson’s The Making of Europe. The monk remains inside his cell nineteen hours a day, leaving only for daily Mass and prayers in the church, a common meal in the refectory once a week, and the Monday walk with others for two hours. Over time, the dwelling space acquires in the monk’s mind a being and character of its own, an evolving one. Dom André Poisson, Prior of the Grande Chartreuse a generation ago, declared the cell “an extraordinarily efficacious instrument . . . the vehicle of grace, so long as we give ourselves up to it.”

8. At The American Conservative, Carmel Richardson focuses on the religion-affiliation crisis, and finds there are more women than men heading for the exits. From the article:

It should be obvious here that the conclusion is not to stuff women in a closet to keep them Christian. Rather, it is unmistakable that the education to be found in most elite institutions of our day is not worth a fraction of the tens of thousands of dollars too many have paid for it. If the result of higher education for women is not increased humility, wonder, and curiosity, of the same sort that drove men and women to God in earlier eras, we can safely assume that they are not being taught much of worth.

Another piece worth considering in this puzzle is happiness. Religiously affiliated Americans are, apparently, happier; they are also more likely to be married, and less likely to get a divorce, which factors probably contribute to that happiness. Happiness is an ambiguous term, and very poorly measured by surveys, and it is worth asking, as my colleague Nic Rowan did recently, whether “happiness” is the point. Nevertheless, the term used by sociologists is helpful for a broad-brush analysis of something that Christians themselves have never needed a survey to understand: That is, young women leaving the church are trading it for a worse life, not a better one.

It is right to look at these trends and have pity. In terms of status, higher education achievement, and religion, there exists a real gender gap. One half of young Americans are less likely to be brainwashed in college, less likely to take on enormous debt for a job, and more likely to find purpose and satisfaction in religion. The other half are women.

9. At Commentary, Seth Mandel scores the despicable efforts to remove Jews from the public square. From the article:

A century ago, public institutions tried to keep Jews out because of quiet social bigotry. Today, the clear aim of the anti-Semites is to firmly plant their suspicions in the public square. Eventually, as the post–World War II era settled in, the drawbridges were lowered and Jews once again thrived at elite universities and medical schools, not to mention in literature and art and entertainment. The mistake back then, today’s clever anti-Semites clearly understand, was relying on people themselves to continually refresh the spring of exclusion. The enemies of the Jews now seek to bypass that by codifying their characterizations of the Jewish people—in government resolutions, school curricula, and in some cases the return of loyalty oaths. They are re-waging the post-WWI battle against Jewish participation in American life while this time hoping to salt the earth behind them. . . .

In November, an Oakland city council meeting turned into a raucous carnival of blood libels. Before voting on a cease-fire resolution, which was ultimately unanimously passed, a council member suggested adding language condemning Hamas. A chilling public-comment period followed. “Israel murdered their own people on October 7,” said one resident who was, like many of her fellow Oaklanders, keffiyeh-clad for the occasion. Many read statements likely prepared for them by pro-Hamas advocacy organizations. “Calling Hamas a terrorist organization is ridiculous, racist, and plays into genocidal propaganda that is flooding our media and that we should be doing everything possible to combat,” said one. “I support the right of Palestinians to resist occupation, including through Hamas, the armed wing of the unified Palestinian resistance,” recited another. “The notion that this was a massacre of Jews is a fabricated narrative,” yet another dutifully read from her phone. One man compared Hamas to a battered wife. A woman asked: “Did anyone else notice that those who oppose this resolution are old white supremacists?”

10. At National Review, Jeffrey Blehar takes on the controversial and ideological boss of National Public Radio, Katherine Maher. From the piece:

For Maher turns out to be quite ideologically coherent in her own way—except that her ideology is repulsively antithetical to any institution with pretensions of objective news-gathering and reporting. The tone of her speeches is notably more controlled than that of her social-media feed; she presents reasonably well, which will always get you far in corporate America (particularly provided you also have incredibly wealthy and well-connected parents in New York City finance). But the same dead-souled, robotically woke relativism haunts her every assertion and underlies all her premises. No wonder Berliner spit the bit at this woman bringing her ethos explicitly to National Public Radio.

Maher’s TED talk is titled “What Wikipedia Teaches Us about Balancing Truth and Beliefs,” and if you have 15 minutes to set aside as a calm-voiced Stasi interrogator gently jabs a screwdriver into your eardrums, it’s worth listening to in full to get a sense of her Orwellian worldview. Her primary takeaway from her experience running the Wikimedia Foundation (which oversees Wikipedia) during “a global crisis of fake news and disinformation” is that, since “your” truths are purportedly as valid as “my” truths, truth and facts are therefore illusory: We should instead work with experts to create a “minimum acceptable truth,” a process governed by a social consensus that substitutes for the real thing. (The example she uses to illustrate this, naturally, is how “disinformation” about climate change prevents people from realizing the “truth” that governments need to implement radical economic and social reforms to end carbon emissions in the West. I am not kidding. She is nothing if not perfectly predictable.)

11. At The Blade of Perseus, Victor Davis Hanson thinks Iran may have spent all nine of its lives. From the piece:

How does Iran get away with nonstop anti-Western terrorism, its constant harassment of Persian Gulf maritime traffic, its efforts to subvert Sunni moderate regimes, and its serial hostage-taking?

The theocrats operate on three general principles.

One, Iran is careful never to attack a major power directly.

Until this week, it had never sent missiles and drones into Israel. Its economy is one-dimensionally dependent on oil exports. And its paranoid government distrusts its own people, who have no access to free elections.

So Iranian strategy over the last few decades has relied on surrogates—especially expendable Arab Shia terrorists in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, along with the Sunni Arabs of Hamas—to do its dirty work of killing Israelis and Americans.

It loudly egged all of them on and then cowardly denied responsibility once it feared Israeli or American retaliation.

12. At the Jacksonville Daily Progress, Michelle Dillon reports on a Texas fundraiser that did a bang-up job of raising money. From the story:

The 10th annual Kiwanis Shootout was conducted Saturday, April 13, with 22 teams participating. The yearly event is the single fundraising event for the Jacksonville Kiwanis Club.

Wayne Beal, for the fifth year running, hosted the event at his 500-acre ranch.

Beal said as a rancher he never had time for civic or service clubs, but providing a venue for the Kiwanis event was his way of contributing. While he doesn’t participate in the shooting contest, he spends the day at the shootout visiting with people. . . .

Proceeds from the event are used by the Kiwanis to support various youth-focused charities and non-profit organizations throughout the year.

Lucky 13. At City Journal, Mark Mills scores the fantasy of a world without fossil fuel. From the analysis:

Given the magnitude of money at stake, and the centrality of energy, it’s rarely been so important to recognize the difference between pessimism/optimism and realism. There is much to be optimistic, even excited, about regarding the emergence of new technologies. But the overwhelming majority of innovations throughout history have been with energy-using, not energy-producing, technologies. Put differently: humanity’s imagination is far more fecund when it comes to finding ways to consume energy than to produce it. That’s one of those ineluctable realities of the universe. The options for producing energy are surprisingly limited, and new possibilities await the arrival of new physics. That arrival is certainly imaginable, indeed almost inevitable, but also irrelevant for the purposes of what we can build in the next decade or two.

The transitionists, however, hold it as axiomatic that the world is witnessing a foundational tech revolution within energy domains—hence their hyperbole about “exponential progress” and terms like clean tech, energy tech, or climate tech, meant to invoke the exponential growth in computing and communications. In that worldview, the hyper-spending is a way to accelerate the inevitable emergence of the “new energy technologies” (the preferred term in China). Silicon Valley’s seemingly rapid production of other game-changing technologies (all energy-using) and globe-straddling companies have yielded an article of faith that, when enough money goes to enough smart people, amazing innovations will happen. The IMF economists phrased it thus in a report enthusing about an energy transition: “Smartphone substitution seemed no more imminent in the early 2000s than large-scale energy substitution seems today.” The transitionists use many variations of that analogy, but it is a category error on two counts.

Bonus. At The Spectator, Julie Burchill finds that Marilyn Monroe continues to be dehumanized. From the beginning of the piece:

What do we talk about when we talk about Marilyn Monroe? Sex, death and everything in between. Unlike other legendary film stars from Garbo to Bardot, Monroe has become (to use that awful and over-popular word) “iconic”—which is “problematic” in itself. Being recognizable as a hank of blonde hair and a white dress failing to preserve her dignity dehumanizes Marilyn—and we know that being treated as a “thing” contributed towards her terminal sorrow. We want to have our cheesecake and eat it, without adding the heavy weight of posthumous complicity in the death of this likable young woman—which is what Monroe was, beneath all the glamour and the pain.

Garbo and Bardot—both of whom were tough and uncontrollable—retreated and retired on their own terms while in their thirties; Monroe, who was damaged and manipulated, died in hers, which made her a perfect dream girl. You can’t libel the dead; Marilyn’s death made her once more a blank slate that any inadequate man could scrawl obscenities on. Hugh Hefner never stopped; he started out by digging up Monroe’s impoverished past when the first issue of Playboy in 1953 announced “First time in any magazine full color the famous Marilyn Monroe nude” and ended up being buried next to her at the Westwood Village Memorial Park cemetery: “Spending eternity next to Marilyn is too sweet to pass up,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 2009. He never met her, but he was her most famous stalker; it’s pleasing now to see his own persona being dragged so relentlessly by his last wife, who when promoting her book recently appeared still shell-shocked from submitting to his gnarled caresses. Now it transpires that Marilyn, who was bothered by so many lecherous men during her life (her essay in Motion Picture Magazine, “Wolves I Have Known,” was very likely the first thrown stone of #MeToo, half a century before it existed) will be partaking of eternal rest in a lecher sarnie, as the crypt on her other side was bought earlier this month by one Anthony Jabin—a “tech investor”—for $195,000, who smarmed “I’ve always dreamt of being next to Marilyn Monroe for the rest of my life.”

Lechers gonna lech.

For the Good of the Cause

Uno. At Philanthropy Daily, Hans Zeiger pays tribute to Jack Miller, a consequential philanthropist. Read it here.

Due. C4CS is hosting an important, three-hour “In the Trenches” Master Class on Major Gifts, and any nonprofit worker bee who has anything to do with soliciting support and developing relationships with donors of means would be well advised to participate in this webinar, which takes place on Thursday, May 16th (from 1:00 to 4:00 p.m., Eastern). There’s much to learn, and much regret to be had from not registering. Get more information, and sign up—do that right here.

Department of Bad Jokes

Q: What do you call a werewolf who doesn’t know he’s a werewolf?

A: An unawarewolf.

A Dios

This intense madness and depravity has been a long time fermenting, the soil tilled and fertilized by the most wretched of ideologues. Corrupting the minds of the youth won Socrates a cup of hemlock. Nowadays, it earns you tenure. A few millennia later, a Daily Mail headline reads, “Defund Columbia: Robert Kraft pulls his money as other donors blast 'f*****g crazy' anti-Israel mob but staff join students' campus protest in spiraling crisis.” Good for you, Mr. Patriots Owner, but did it have to come to this—our quads serving as platforms for diabolical chants—for you to stop giving? Wasn’t it obvious a year ago, a decade ago, a generation ago, that philanthropists were bankrolling not so much education but insanity? God help us.

May We Be the Stone, Rejected and Yet Repurposed,

Jack Fowler, who knows nothing about being stoned, but a lot about being sloshed, and who sleeps it off at jfowler@amphil.com.