Dear Intelligent American,

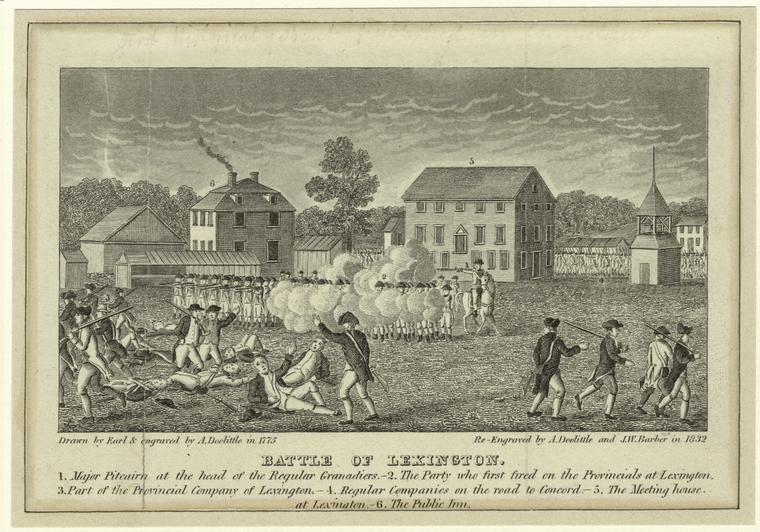

The anniversary (today) of the Battles of Lexington and Concord—so short-shrifted by historians for actions that proved so immensely consequential to mankind—prompts one to wonder: Do schoolboys and -girls know of Emerson’s hymn about embattled farmers who “fired the shot heard round the world”?

Why should they, when their moms and dads don’t?

More wondering: Who was the first to die at this hinge of history? On the Lexington Common, the British regulars, when ordered to fire, did so, but over the heads of the straggly band of minutemen, fewer than four dozen facing hundreds of redcoats. Their officer, Major John Pitcairn, bellowed: “G— d— you, fire at them!” The second volley found targets.

The first American to die seems to have been Jonas Parker. The father of nine, aged (55) for soldierly duties, was mortally wounded from the second volley. Staggering, and determined to stand his ground, he managed to return fire before he was finished by a British bayonet thrust.

Seven others died at Lexington, and more were wounded before the hostilities shifted to the Concord Bridge, and Fortune’s ill winds blew strongly against the Brits. An opinion: Colonials who engaged that day deserve to be remembered. Should you agree, consider reading Frank Warren Coburn’s The Battle of April 19, 1775, in Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville and Charlestown, Massachusetts. Find it here.

Don’t Shoot Until You See the Links of Their Excerpts!

1. At UnHerd, Nicholas F. Jacobs and Daniel M. Shea consider a controversial new book, White Rural Rage, and find it showcases the dissolution of progressive empathy. From the piece:

Still, rageful stereotypes sell better than complex backstories. And they’re easier for our political and media ecosystems to make sense of. Reference some data point about QAnon conspiracies in the heartlands, and you’ll raise more money from nervous liberals in the city (who just so happen to live next to three times as many conspiracy believers). Lash out against the xenophobia in small towns, and you’ll mobilise your city voters to the polls. Rage draws clicks. It makes a splash.

However, unlike rage, which is explosive and directed towards immediate targets, scholars have shown that resentment in rural areas emanates from a sense of enduring injustice and marginalisation. It is not primarily about anger towards specific groups such as black Americans, immigrants, or LGBT individuals. Instead, resentment or grievance is a deeper, more persistent feeling that arises from real and perceived slights against rural communities. These include economic policies that have devastated local industries, a lack of investment in rural infrastructure and education, and a sense of cultural dismissal from urban-centric media and politics.

2. At Verily Magazine, Tina Evans endures a test of fire, providing an example of how moms are made. From the piece:

They sent my eight-week-old for a CAT scan, which revealed cysts on the brain. Then my only child went in for surgery, where they drilled a hole in the skull to extract and test the liquid: citrobacter. A rare form of bacterial meningitis.

I can still smell the room they sat me down in and confidently told me they thought my child would survive this, but the best-case scenario I could hope for was my little one needing help to walk and talk.

I was bereft. I held this tiny human who had grown inside me and tried to face the possibility of losing my baby or needing to do everything for this little person. It was too much to deal with, so I pushed it down and put one foot in front of the other. I got us settled on the hospital ward and made it our new home while they took my baby for another surgery to put a central line in. That’s a drip for antibiotics that goes into the heart. There’s no way to get used to seeing that.

My local doctor told my mom that considering the prognosis and loss of quality of life, it might have been better for my child to not survive. Hearing that devastated me. But I couldn’t control that. All I had the capacity to do was concentrate on giving my child the best hospital experience ever.

Yes, a Commercial, but a Good One . . .

You simply gotta attend the forthcoming Center For Civil Society webinar on “American Jews, Philanthropic Traditions, and Harsh New Realities,” featuring a trio of experts—Alexandra Rosenberg, senior director of development at Tikvah, Rebecca Sugar, author and longtime leader in Jewish philanthropic management, and Rabbi Rob Thomas, cybersecurity expert and philanthropist—discussing an ancient faith and its unique practices and philosophy of charity, conducted in and contributing to the tapestry of the USA (a country supposedly intolerant of intolerance). This free event takes place next Thursday, April 25th, via Zoom, from 3:00 to 4:00 p.m. (Eastern)—register right here.

Now, We Return to Vibrant Content! . . .

3. At The American Conservative, Nic Rowan, former fare jumper, confesses and expands. From the piece:

When I had my first job, I maintained my excuse. Now I had rent, utilities, and a whole host of other adult expenses to pay for—why should I add the Metro, which I had never paid for anyway? Still, I had a conscience. I understood that it was one thing to dodge fares as some puke kid in high school; it was quite another to do the same thing as a white-collar professional in Rosslyn, Virginia. And so I developed a strange habit of pretending to pay for the Metro: Whenever I walked quickly behind another commuter, I swiped my old Library of Congress reader’s card to give the impression to anyone who might be watching that I too was a paying customer.

Sometimes I consoled myself that one day I would pay for the Metro. But later, always later. After all, I said to myself, what’s the harm in a little vice now and then? Some people swipe sugar cubes at diners; I steal swipes at the train station. I called it a private amusement. Soon, I began to approach all sorts of little things with this kind of Huck Finn logic. I found myself nicking coffee cups, beer glasses, and bread plates from restaurants. I took old street signs, defunct newsstands, unused office furniture. Of course, I never took anything of much value. That would be real theft, or so I told myself.

I could go on in this vein for many more paragraphs, analyzing my motivations and self-justifications in Nicholson Baker–like detail. But I fear that would be tedious, since the outline of this story is already familiar to most people. What had begun as a series of arbitrary adolescent decisions hardened into habit, and habit, as they say, becomes character. I don’t know how corrupt I became—I certainly never evaded taxes or anything of that nature—but when I look back on those years, I detect something flippant, an offhand lack of respect for other people, the law, my home city. I don’t like it. I suppose it could have developed into something more ugly, but it would be almost as bad if I lived the rest of my life in the manner I’ve just described.

4. Over There: At The European Conservative, Shawn Phillip Cooper urges enduring it—the challenge of attending the opera. You might not regret having done so. From the piece:

During my college years, two things effected a great change in my attitude towards opera. The first was watching through the complete production run of the 1987-2001 television series Inspector Morse, originally broadcast on ITV in the UK, but available to me on DVDs (as it then was) via Netflix. The series is one of the greatest detective dramas ever made. Its titular main character has sophisticated tastes and a devotion to opera music, in stark contrast with the working-class upbringing of his colleague, Detective Sergeant Lewis. In the final episode, “The Remorseful Day,” Morse has a brief but serious exchange with Lewis about opera music, telling him, “You know, you really should persevere with Wagner, Lewis. It’s about important things: life and death, regret.” The episode is itself an emotionally-laden farewell about life, death, and regret, and I was inspired to take Morse’s advice to heart; Lewis, for his part, got his own sequel television programme (Lewis, 2006-2015), in which it is revealed that he also took up listening to opera.

At around the same time that I was studying Immanuel Kant’s third critique (which, among other things, attempts to elucidate beauty and the sublime) and watching Inspector Morse, I was beginning to listen to the music of composers who worked in minimalism, such as Ludovico Einaudi, Alan Hovhaness, Arvo Pärt, and Philip Glass. Having previously given such music short shrift (I had instead been a sucker for the Romantics), a chance encounter with Hovhaness’ Symphony No. 22 “City of Light” proved life-changing. Here was Kant’s sublime in all of its vast grandeur—a realisation that at once bridged Romanticism and minimalism. When I sought out other similarly soul-shaking works by other composers, I eventually came to Glass’ opera Akhnaten, and at once my view of the genre was mirrored by the opening lines of the libretto:

Open are the double doors of the horizon.

Unlocked are its bolts.

5. At Acton Institute’s Religion & Liberty Online, Noah Gould checks out a documentary that investigates the roots of college free-speech wars, and finds they are initiated before the campus is even seen. From the piece:

Extreme behavior that plays well in the documentary—screaming at campus speakers, mental breakdowns, etc.—while deeply concerning, is a sideshow to the root issue. Certainly these problems must be addressed, especially the framing of all issues around the “isms” of race, sex, and class. But by the time students reach college, their “upbringing” is essentially over. What happened to the average student before they arrived in the college dorms? One possibility is that they had such a weak education at a young age that, when they encountered the ideas prevalent at their various universities, they immediately embraced them, having had no training in critical thinking or the benefit of questioning the basis of any status quo. A second possibility is that they were already receiving the same type of fragility conditioning during their grade school and teenage years. You don’t get a coddled generation from just four years of college. . . .

We need to explore exactly how parents can move away from a model of fragility. Numerous barriers exist. Since the rise of “parenting styles” in the 1960s, we don’t raise children in community. No longer can you—a conscious adult—tell off someone else’s kid for biting your kid on the playground for fear his mom may be offended that you imposed your “parenting style” on her progeny. Raising kids in community, however, would allow them to experience free play within the boundaries of other parents’ guidance, which would curb the worst behavior.

6. At National Review, Mark Milke looks north and sees a Canada where the legislative elites are fixated on 1984. From the piece:

In late February, the Liberal government introduced draft legislation in Parliament, Bill C-63. It purports to increase online protection for children. Officially named the Online Harms Act, that part of the legislation is laudable.

But what is not praiseworthy are the tacked-on provisions that would further restrict the rights of Canadians to speak, debate, and dissent. For example, the bill would create a “hate crime offence,” which in the eyes of government is “content that foments hatred.” Such hatred is defined in the bill as that which “expresses detestation or vilification of an individual or group” based on categories in the existing Canadian Human Rights Act.

For those outside Canada not familiar with the list, it’s all-encompassing: anyone “motivated by hatred based on race, national or ethnic origin, language, colour, religion, sex, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation, or gender identity or expression.” To helpfully define “hatred,” one aspect of the bill adds this clarification: “Hatred means the emotion that involves detestation or vilification and that is stronger than disdain or dislike.”

Note that in this case it’s not actions that would be outlawed but thought, the key word being the allegation that someone might be “motivated” by hate to speak against the cited list of groups. Note as well that a civil servant in the human-rights bureaucracy would have a hand in deciding whether or not the accused has engaged in emotions “stronger than disdain or dislike” and is therefore potentially subject to a Criminal Code charge.

7. At National Affairs, Marco Rubio ruminates on American industrial policy. From the essay:

Using government to support industry and defend our economic and national security is nothing new for America, nor is it a departure from American conservative principles. And despite assertions from critics that free markets alone are responsible for America’s success, plenty of evidence indicates that industrial policy played a vital role in building our nation into a world power.

Such evidence can be found in the earliest days of the republic. The first secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, famously favored using subsidies to foster domestic manufacturing and “render the United States, independent on foreign nations, for . . . essential supplies.”

One early example of this policy is the national arsenal, built on a site personally selected by George Washington near Springfield, Massachusetts. The arsenal began as a store for arms manufactured abroad, but within a few years of America’s independence from Britain, it was producing small arms that made our nation less reliant on foreign powers for defense. The benefits of the arsenal spilled over into the commercial economy, with skilled labor and workshops concentrated in a small geographic area transforming the Connecticut River Valley into the nation’s first major manufacturing hub. “It would not be hyperbole,” notes historian Robert Forrant, “to call [this] collection of firms . . . the ‘Silicon Valley’ of its day.”

8. At Tablet Magazine, Maggie Phillips, concerned about the rise of irreligiosity, finds a San Francisco salon where the “nones” congregate. From the article:

When they met through a mutual friend, both had been thinking in parallel about similar themes. Melamed was interested in the “meaning crisis,” a term that YouTuber, philosopher, and cognitive scientist John Vervaeke helped popularize. Vervaeke defines the meaning crisis as “the loss of spiritual vitality, and the sense of disconnection we experience with other people, ourselves, and the world at large.” And Melamed was also concerned with another crisis: the “metacrisis,” a theory of humanity’s struggle to engage collectively with problems in a globalized information economy, where traditional institutions and means of relating to one another are breaking down or fragmented.

His guiding question, Melamed said, was, “How do we create a place where the ethos is one of art and play? A place where we explore for the sake of exploring and try to understand things for the sake of understanding, and try to create things for the sake of just creating things, and do that with a sense of community.”

Nonreligious spaces for community have been cropping up to fill the church-shaped hole in American life. There is the Sacred Design Lab, whose consultants translate practices from a variety of faith and wisdom traditions to help secular institutions cultivate community and connection. Peoplehood, from the creators of SoulCycle, offers a “weekly practice” for its paid members, in which “Gathers” of up to 20 people come together to share and listen. They offer other events, such as sound baths, breath work and stretching sessions, and game nights, all intended to build connection and combat loneliness.

9. At The Lamp, Dan Hitchens goes to the historic Canterbury Cathedral and finds . . . a disco. From the piece:

At evensong, we are told to exit by a different route than usual, due to “an event in the nave.” Everybody knows what it is. “Are you going to the disco, David?” one elderly parishioner asks the dean on his way out, with an illustrative swivel of the hips. My D.J. from the train attends the service, slipping out early to go and set up. The Gospel reading echoes around the quire: “Then the other disciple, who reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed; for as yet they did not understand the scripture, that he must rise from the dead.” Observing rather than participating, and noting the empty altar where the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass no longer takes place, I think of the “outlandish papists”—foreign Catholics—whose presence was noted in the 1640s when they came to pray before the carving of Christ on the South Gate.

Outside it’s cold, dark, and pouring with rain, and the queue is already forming for the first silent disco session. So is a prayer vigil organized by Skowronski as an act of spiritual reparation. “Our beef is very much with the custodians,” he says, as opposed to with the partygoers. “I think most people are so detached from the sacred that it’s just a cool thing to do, a novel thing to do.” Afterwards he tells me that people kept joining the vigil by mistake. “They thought we must be going to the disco because most of us were in our twenties. We had to tell them, no, the queue is the middle-aged people over there.”

It is indeed a somewhat older crowd. “I’m here because I’m a Nineties girl!” one woman announces to me, displaying a brilliant-white pair of platform trainers. Two quiet forty-something ladies, who would not be out of place at a parish cake sale, remark afterwards that they admired how “respectful” the whole thing was and how many security guards were in attendance. Among the partygoers, consensus holds that the protesters have a point. “Serving alcohol is a bit much,” says one. A group of teenagers conceded that the cathedral is a “historic site.” But there is, they argue, another side to local identity: “Canterbury is a party city. It’s a student city.”

10. At Law & Liberty, Luis Pablo de la Horra looks at the life and work of the late Daniel Kahneman, who thought a lot about thinking. From the essay:

According to Kahneman, human behavior deviates significantly from perfect rationality. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, which encapsulates decades of research in behavioral economics, Kahneman argues that decision-making is governed by two distinct systems: System 1 and System 2. System 1 functions automatically and effortlessly, with little or no sense of voluntary control. It is responsible for intuitive judgments and immediate decisions via mental shortcuts or heuristics. In contrast, System 2 is slow and analytical. It demands our conscious control and is engaged in complex decisions requiring significant mental effort.

We often view ourselves through the lens of System 2: as beings of reason who base our choices on rational thought. Yet, in reality, we rely on System 1 far more frequently than we might believe, leading to consistent and predictable mistakes, i.e., cognitive biases. Kahneman, in collaboration with his colleague Amos Tversky, delves into these heuristics and biases, often using experimental methods in his research.

When making decisions, we tend to overestimate the importance of readily available information (availability heuristic); rely too heavily on the first piece of information we encounter (anchoring bias); draw conclusions from small samples of data (law of small numbers); ascribe more value to things simply because we own them (endowment effect); value losses more than equivalent gains (loss aversion), a principle central to Prospect Theory developed by Kahneman and Tversky; and overestimate our abilities and performance (overconfidence bias), among other noted biases.

11. At Commentary Magazine, Christine Rosen harps on the MSM for its effectively deliberate downplaying of news about antisemitic acts. From the article:

Why aren’t these anti-Semitic attacks front-page stories? Why aren’t they given the kind of relentless scrutiny that anti-Semitism on the right has properly received in these same outlets? The Times has published countless stories about the rhetoric of participants in the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Where are the big-think pieces and deeply reported stories about the organizations and funders behind the anti-Jewish groups staging protests outside synagogues and other Jewish institutions?

It’s not as if their readers and viewers are unaware of the problem. According to Pew Research, the percentage of Americans who say Jews face discrimination has doubled from 20 percent in 2021 to 40 percent in 2024. And yet, for some reason, mainstream-media outlets seem to be the only ones who haven’t drilled down on the issue.

In fact, the decision to downplay the anti-Semitic threat from the left is deliberate. Left-leaning media do not like to cover the behavior of their own, as the inconsistent coverage of the Jew-baiting members of the Democratic Party’s “Squad” during the past several years attests. Mainstream reporters at outlets like the New York Times take great pains to provide context and explanations for Representative Ilhan Omar’s blatant anti-Semitism, for example. A 2019 piece gave Omar and her defenders ample space to claim she was being unfairly targeted for criticism because she was a progressive Muslim woman while glossing over the fact that she had repeatedly accused Jews of having dual loyalties.

12. At Washington’s NCWLife.com, Kasey Safford reports on a Wenatchee fireman’s lake swim to raise funds for kids with desperate medical needs. From the article:

Wenatchee firefighter Capt. Brandon Kunz, who completed a solo swim across Lake Chelan in nonconsecutive segments last September, has nearly doubled his original $10,000 GoFundMe goal in honor of Baby Jacqueline Grace.

Kunz swam the 50-mile length of Lake Chelan to raise money for the Greatest Needs Fund at Seattle Children’s Hospital, which helps families affected by unfortunate medical circumstances. Friends of Kunz lost their infant daughter, Jacqueline Grace, shortly after birth due to heart development issues. . . .

On Sunday, high winds and a drop in temperatures forced Kunz to pause his swim to perform a rescue swim for the kayaker of his safety team who had been thrown overboard due to the incredibly steep waves.

Kunz’s concluded his swim with roughly $18,500 raised and has now raised $19,467.

Lucky 13. At The American Spectator, S.A. McCarthy encourages readers to find lessons from the life of crotchety novelist Evelyn Waugh. From the essay:

However, Waugh had a cruel streak, and he struggled to reconcile this with the charity demanded by the Church. In one infamous instance, Waugh’s bullying caused a young woman to leave a party in tears. His friend Nancy Mitford asked him how he could possibly be so callous and still call himself a Catholic. The bully par excellence responded with both wit and a strange sort of humility, “You have no idea how much nastier I would be if I was not a Catholic. Without supernatural aid I would hardly be a human being.” It takes a great deal of faith to admit that you are, in fact, a wretch in need of aid.

But Waugh did exercise charity. While serving as a commando in World War II, alongside Randolph Churchill, Waugh rescued many persecuted Jews in war-torn Yugoslavia, offering financial assistance and making sure that many were able to escape the brutalities of both the Nazis and the communist revolutionaries led by Marshal Tito. Waugh also managed to write up reports for the British Foreign Office and Pope Pius XII on the persecution of Yugoslav Catholics under the communists.

“The Church,” Waugh once wrote, “is the normal state of man from which men have disastrously exiled themselves.” Over the course of his life, Waugh sought to return to that “normal state of man” and end both his earthly and spiritual “exile,” amid an age of rapidly shifting political standards and rapidly decaying moral codes.

Bonus. At The Frank Forum, Frank Filocomo offers a guide with several tips for becoming a communitarian. Here are two recommendations:

Send the elevator back down. My dad repeats this one ad nauseam. If you take the elevator up to the tenth floor, you should make it a habit to send it back down to the first floor as you get off. This is a small deed, but a thoughtful one.

Shame your friends for littering. We ought to take pride in our communities. There should, therefore, be zero tolerance for littering. Most littering, I would wager, is not deliberate. Your friend, for example, may go to toss an empty bottle of water into a garbage can, only for it to miss and land in the street. Indifferent, your friend may just keep on walking. Don't let them. Tell them to go back and pick it up. Try not to sound too sanctimonious when doing this, though.

For the Good of the Cause

Uno. Save those dates! October 23-24. And mark the location! Pepperdine University in Malibu, CA. Why? Because that’s when and where the Center for Civil Society will be hosting its 2024 Givers, Doers, & Thinkers conference, this one on “K to Campus: How the Education Reform Movement Can Reshape Higher Ed.” Agenda and speakers will be announced soon, but registering, getting info, and all such stuff can be done and found right here.

Due. C4CS is hosting an important, three-hour “In the Trenches” Master Class on Major Gifts, and any nonprofit worker bee who has anything to do with soliciting support and developing relationships with donors of means would be well advised to participate in this webinar, which takes place on Thursday, May 16th (from 1:00 to 4:00 p.m., Eastern). There’s much to learn, and much regret to be had from not registering. Get more information, and sign up—do that right now, why dontcha?!—right here.

Tre. With MLB way under way, at Philanthropy Daily, Andrew Fowler (could he be related to Yours Truly?!) tells about the rich history of the Knights of Columbus, its mission of charity, and the National Pastime. Read it here.

Department of Bad Jokes

Q: Why do bees have sticky hair?

A: Because they use a honeycomb.

A Dios

Repent! We’re talking to you PBS, which fell far short of capturing Boss Bill Buckley in its “American Masters” documentary. Interested in some reviews? Good: At Chronicles, Emina Melonic called out An Inept Takedown of William F. Buckley; at the New Hampshire Union Leader, columnist Daniel McCarthy charged that PBS misremembers William F. Buckley Jr., and at National Review, Alvin Felzenberg penned WFB & Civil Rights: Correcting the Record while Neal B. Freeman told us What the PBS Documentary Misses. Now don’t say you weren’t told.

May Drooping Spirits Find Restful Waters,

Jack Fowler, who is reviving at jfowler@amphil.com.