Dear Intelligent American,

Approacheth now that verdant day when parades break out and bagpipes croak and wool sweaters temporarily part from the mothballs, all that and the warbling of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem coalescing to celebrate hereabouts the heritage of a nation whose millions of tired and poor and hungry traveled west across the Atlantic (coming this way, or, permitting a movie reference, Going My Way) to populate and shape the culture of this great Nation.

As for the country and its famines left behind, its soul—steeped in Christianity once, of Saints Patrick and Brendan and Brigid and a people who boast of saving civilization—has found itself on a secular bender. At times it seems as if the cock has crowed, with the prevailing cultural brouhaha hearkening to the chaos of Tim Finnegan's wake.

Quo Vadis, Ireland? Have your people raised the parting glass to Eire’s essence?

Maybe not. Last week, the citizenry said Ní hé, soundly rejecting two referenda to amend the country’s constitution. The efforts, pushed mightily by Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar and the nation’s egg-faced political elite, “would have broadened the definition of family and removed language about the social value of women within the home.”

While we beware the Ides of March, let us open a Jug of Punch and toast the outcome!

We Stand and Deliver, Offering No Bold Deceptions but Excerpts Galore

1. At Tablet Magazine, Seth Kaplan recommends that Americans look at the country’s Orthodox communities for powerful examples of how to strengthen civil society and respond to the cultural maladies prevailing in our neighborhoods. From the essay:

That, alas, is not the whole story. Social decay and disconnection extend into the most middle-class and affluent areas of the country. For too many, upward mobility has also been an engine of isolation and alienation. Outsourcing care for our children, elders, and even ourselves to others may seem like a perfectly rational—if not obligatory—way of managing various challenges efficiently. But John McKnight and Peter Block, authors of The Abundant Community, cite this rise in professional “purchase care” as a replacement for “freely given commitment from the heart” as one reason why even neighborhoods that are economically well off can be socially impoverished, and fragile.

One notable exception to these trends is Orthodox Jewish communities, which retain embodied and embedded practices and the institutions that sustain them. While offering ample opportunity for individuality, Judaism makes place-based community the main organizing structure of life in a way that no other faith does. It does this by marking both time and space in distinct ways. The fruit of these boundaries can be seen in any Orthodox area—where the degree of interaction between people stands in sharp contrast to just about any other place in America.

While Shabbat and festivals bring us closer together, a whole slew of overlapping institutions—some clearly religious (synagogues, mikvot, schools, batei din), others less so (kosher restaurants and markets, gemach loan societies, charity funds, after-school activities, interfamily support groups)—embed our lives in social relationships, groups, and activities that not only provide meaning and companionship, but sustain or propel us at critical junctures. Together, they nurture a sense of trust, willful interdependency, and security that is too often missing in other American neighborhoods.

2. At The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, Mariusz Ozminkowski warns that DEI has been accessorized with a new weapon. From the analysis:

For a few years now, individual campuses of California State University have been considering turning what seemed like just another grievance into an opportunity to promote a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) agenda.

A typical university policy statement (such as this one from California State University, Fullerton) reads, “Faculty members from traditionally underrepresented groups may experience additional demands on their time, a phenomenon termed ‘cultural taxation.’ Cultural taxation involves the obligation to demonstrate good citizenship towards the institution by serving its needs for ethnic representation and cultural understanding, often without commensurate institutional rewards.”

An article promoted by the California Faculty Association further explains that “minority faculty are expected to serve as role models and mentors for minority students.” It adds, “Clearly, serving on university and department committees as the ‘minority’ representative is taxing in itself. But being expected to ‘speak for your people’ as well, is a form of ‘taxation without representation’ at whose mere consideration, would make most faculty shudder” [sic].

Really?

3. At Reason, the great Bruno Manno explains that public funding supporting religious education remains, despite recent SCOTUS verdicts, colored by ambiguities. From the piece:

Between 2017 and 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court issued three rulings that rang the death bell for state-level Blaine amendments: Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, and Carson v. Makin. Education law expert Charles J. Russo wrote in an April 2023 article in America: The Jesuit Review that these rulings open up “more ways for public dollars to support faith-based education.” But federal constitutional questions remain unresolved on three important school-choice funding issues.

One such issue involves the public/private Blaine amendments still active in some states. These ban aid to all private schools, religious or nonreligious. For example, the Alaska constitution’s Article VII, Section 1 on “Public Education” states that “No money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institutions.”

Most state courts have interpreted these laws as barring aid to private schools, not to students who attend them. But a few state courts—like those in Alaska, Hawaii, and Massachusetts—have been more restrictive and do not allow programs that aid even students of private schools. In light of these recent Supreme Court decisions, those laws are now open to potential challenges.

4. At The American Conservative, Carmel Richardson tracks France’s march to enshrine abortion rights, and finds in the grim scenario a warning for America. From the piece:

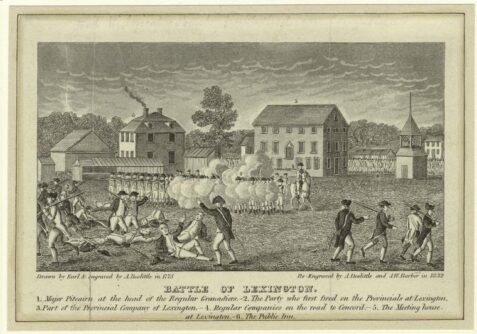

For those Americans watching, this is not just political theater. France moved to make abortion sovereign this week precisely because the United States Supreme Court has said that it is not, at least not according to the U.S. Constitution as currently written. This is the contagious nature of rebellions which so concerned the American founders. Considering their own revolt would inspire the events leading to the Reign of Terror in France, which in turn spurred the 13-year bloodbath in Saint-Domingue, as Haitian slaves overthrew their French colonial masters, it was a reasonable concern.

But perhaps it is the particular nature of France to be cataclysmic. It is there that the egalitarian ideals of the Enlightenment have their origin and most poignant picture, and many of the same ideals are responsible for our current inverted mores on the question of infanticide. Revolutionary France saw the “rights of men” through the lens of immediacy—the rights of these men, often paid for with the lives of others—in a sense the American colonists, with their concern for posterity, did not. Similarly, the rights of women today have been underwritten by the blood sacrifice of the unborn. Of all the nations to make abortion a constitutional right first, it is not surprising that it was France.

5. At Plough Quarterly, Alan Koppschall tells of a community that gets intimate at a special, local café—part of a growing movement that focuses on repairing things, not serving lattes. From the article:

The repair café movement arrived in New York’s Hudson Valley in 2013. Since then, volunteers have started over fifty such “cafés” in the area. The concept is simple: people bring a broken household item—garden clippers, a chair, kitchen knives, a lamp, even jewelry—to a neighborhood location, and volunteers try to fix it for them. If a spare part is needed, the item’s owner will purchase it, but the labor is free.

Only four years before the first repair café opened in New York State, Dutch journalist and environmentalist Martine Postma founded the world’s first in Amsterdam. Distressed by “throwaway culture,” in which businesses design products with intentionally short lifespans, she realized that many people had lost the skills of repair. To rebuild a repair culture, Postma gathered her fellow fixers and invited Amsterdam residents to bring their broken items. “A repair café is a neighborhood meeting place where you, with help from skillful volunteers, can repair your things,” she told journalists. “It’s fun: you meet people from the neighborhood and you also help the environment.” The movement grew quickly to 2,500 repair cafés worldwide. . . .

As a Port Jervis local, Pete feels a responsibility to his hometown, one of the poorest in New York. This motivated him and Katie to found the repair café. By offering to repair broken items for free, they hoped to build a culture of repair among their neighbors. They tell me that repair shop owners in other towns, rather than dreading the arrival of a free repair café or fearing the loss of business, welcomed them. Once people learn that a broken item can be fixed, they are much less likely to throw it out and buy a new one.

6. At First Things, Carl Trueman find technological advances have brought about anthropological chaos, and turns back to certain theologians, foes of Nazi Germany, who opposed ideologies that sought to redefine humanity. From the piece:

We have witnessed amazing technological advances since the 1940s. The transformation of humanity from a given, limited, teleological essence to a potency whose limits and ends are merely technical problems to be overcome is now complete (at least in the cultural imagination). Ironically, human technical brilliance has served to make human beings into nothing of any great significance. We are the only creatures on the planet who are intelligent and intentional enough to have abolished ourselves.

Of course, identifying limits and ends is not always as straightforward as we might like to think. Does it break human limits to use planes, calculators, and antibiotics? There are indeed gray areas. But the breaking of certain limits and ends has clear revolutionary significance. When life itself and its intrinsic limits become technical problems to be overcome, the anthropological results are dramatic. This also generates ethical questions that we as a society do not have the tools to answer, precisely because the notion of what it means to be human—the basis for offering answers—is the very thing rendered problematic by technological advances. When abortion is seen as a basic human right and euthanasia is gaining ground across the West, “What is man?” becomes a matter of personal taste, not social consensus. And then there is the matter of frozen embryos. We have created something via our technical abilities that revolutionizes what it means to be human without even realizing that that is what we are doing. We have created anthropological chaos. No wonder there is no agreement on what to do with the results.

7. At Claremont Review of Books, Chris Caldwell finds a Holland so changed and roiling that it has come to embrace the infamous Geert Wilders, he of the firebrand tongue and dyed-blond locks. From the essay:

Aside from their being poorly educated, Wilders’s voters are hard to describe with precision, though Dutch political scientists are trying. At the turn of this century, Wilders’s electoral base seemed to be in heavily Catholic Limburg, his home province—a matter of cultural, not religious, affinity, for Wilders left the Church in his youth. In more recent years, it has been common to say that he is simply the candidate of the losers of globalization: he wins neighborhoods that used to vote Labor and even Communist, like Pekela, near Groningen.

Others say there is considerably more to it than that. “You don’t get to 48 seats with deplorables,” said a veteran Dutch political journalist in December, citing Wilders’s strength in post-election surveys. Turnout in the Netherlands is heavily skewed to the university-educated; 87% of those with advanced degrees go to the polls. If you ended “voter suppression” there, the populists would clean up. (Although that is true in many Western countries, including parts of the United States.) Wilders is winning people who didn’t used to vote. He is winning those who say they “don’t trust politics.” At a time when parents are growing impatient with “purple Friday”—the second Friday in December, when elementary-school children are encouraged by local Gender-Sexuality Alliances to “affirm gender diversity”—he is even winning some Muslims.

The polarization between haves and have-nots is a matter not just of who gets the fruits of prosperity but of who makes the economic and cultural rules. In the wake of Brexit in 2016, Dutch leaders had the idea of turning the national university system into an English-speaking institution, as a way of raking in some of the revenue that foreign students would bring. It worked. . . . Dutch people keep telling pollsters they want university education in their own language; Dutch elites keep telling the people they’re wrong.

8. At Comment Magazine, Amy Julia Becker knows intimately how disability houses need, but also gifts interdependence. From the essay:

People with disabilities often live with obvious needs. These needs might entail assistance with mobility or communication. People with disabilities are perceived as particularly vulnerable. And indeed, the rates of sexual and physical abuse of people with intellectual disabilities are far higher than the general population. Many people with disabilities are immunocompromised, with vulnerability to illness. And people with disabilities are often keenly aware of their limitations. As Amy Kenny explains in her book My Body Is Not a Prayer Request, the physical demands of living in her body take a lot of energy. She talks about energy in terms of “spoons.” There are days when there just aren’t enough spoons.

Still, our culture uses the language of special needs to describe what amount to very typical needs. The need for mobility. The need for meaningful work. The need for friendship. Shelter. Education. Community. When we use the word “special” to describe basic needs, we deny our shared neediness. Moreover, those of us in typical bodies and minds can easily reduce people with disabilities to this position of need rather than understanding neediness as one common aspect of our shared humanity. As the authors of Disabling Leadership write, “disability can be a door into recognizing that human limitation, rather than human strength, is the space in which the leading of Jesus is made known.”

People with disabilities are not simply needy. They are also gifted. They are people within whom the Holy Spirit dwells. They are called to participate in God’s work in the world. Paul’s description of the body of Christ in 1 Corinthians 12 reminds us that each member of the body brings a particular gift and manifests the Spirit of God in ways that the entire body needs. We not only have needs; we need one another. We are not only dependent; we need interdependent relationships of mutual giving and receiving in order to flourish.

9. At Law & Liberty, Auguste Meyrat finds that John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces foresaw what was coming. From the essay:

However, what really makes A Confederacy of Dunces a classic worthy of being read today is how closely and how well it predicts the future—our present. Even if Ignatius was a complete anomaly in his own time, there’s a whole generation of Ignatiuses today: vain, overeducated young adults who can’t hold a job, live healthily, own any property, or maintain a friendship or romantic partnership, and yet often feel proud of themselves. Like Ignatius, they feel qualified to deliver their opinion on a whole range of issues they have no clue about. Without a doubt, if Ignatius existed today, he would likely be an online influencer hosting a popular YouTube channel or podcast that spoke to disaffected men like himself.

This isn’t to say that today’s influencers are quite as pathetic as Ignatius—after all, it takes some effort to create content and market it—but it’s fair to say that there’s an eerie parallel at work. Instead of constituting a productive class of people who can integrate with their community, so many young millennials and older Zoomers make up a passive rabble who lack the capacity to feel shame about their condition. And when circumstances force them to go out and do something, they will do as Ignatius does and make impassioned rants on Tiktok about the innumerable injustices of the modern world. . . .

Although Ignatius would technically qualify as a traditionalist conservative, pushing for a monarchy and lamenting the lack of a “good authoritarian pope” in charge of the then pre-Vatican II Catholic Church, he is effectively a political radical with the same anti-establishment views as any other partisan. He may wax philosophical on his views, but much of it is incoherent and serves to compensate for his own impotence. The same could be said of young adults now who often espouse contrary principles in their politics and culture. A few might commit to political action, but the great majority of young people mainly post memes and rants, paradoxically displaying shocking degrees of naivety and cynicism.

10. At The Everyman, with humbugging about “Christian nationalism” on the rise, Bradley W. Shumaker reminds us of the spiritual nomenclature of many an American city. From the piece:

To native English-speakers, St. Louis/St. Charles (Missouri), St. Paul (Minnesota), and St. Petersburg (Florida) are more easily recognized as being connected to Christian saints. St. Louis is named after the saint (King Louis IX) who served as the king of France, and who was the only French royal to ever have been named a saint. Its nearby suburb was named after Saint Charles Borromeo, an Italian cardinal. The city of St. Paul was named in honor of Saint Paul the Apostle, and St. Petersburg was named after the apostle Saint Peter, the founder of the Church of Rome and the first bishop of Rome (i.e., the first pope).

Other well-known U.S. cities may not be named after saints, but otherwise have been blessed with Christian names. In many cases, unless you speak Spanish or Latin you might not catch the connection. A shining example is Corpus Christi (Texas). In Ecclesiastical (Church/Liturgical) Latin the term means “body of Christ,” which is in reference to the Christian sacrament of Holy Communion. The name was given to the site by a Spanish explorer in 1519, which he discovered on the feast day of Corpus Christi (a moveable feast day which takes place on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday).

While it is technically correct that the city of Sacramento (California) was named after the Sacramento River, the river obtained its name from the Holy Sacrament (also known as the “Eucharist”). In another beautiful example, Santa Fe (New Mexico) is Spanish for “Holy Faith” (note that the words San or Santa also mean “holy” in Spanish). The cities full name when originally founded was La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asis “The Royal Town of the Holy Faith of St. Francis of Assisi.” In another heavenly instance, Santa Cruz (California), famous for its boardwalk, is named after “the Sacred Cross” or “The Holy Cross,” one of the most important symbols of the Christian church.

11. At The Free Press, Rupa Subramanya reminds us that the fight for free speech can be, and is, especially heated in nations where the right is not explicitly recognized constitutionally. From the analysis:

In Ireland, the government is pressing ahead with controversial new restrictions of online speech that, if passed, would be among the most stringent in the Western world.

The proposed legislation would criminalize the act of “inciting hatred” against individuals or groups based on specified “protected characteristics” like race, nationality, religion, and sexual orientation. The definition of incitement is so broad as to include “recklessly encouraging” other people to hate or cause harm “because of your views” or opinions. In other words, intent doesn’t matter. Nor would it matter if you actually posted the “reckless” content. Merely being in possession of that content—say, in a text message, or in a meme stored on your iPhone—could land you a fine of as much as €5,000 ($5,422) or up to 12 months in prison, or both.

As with Canada’s proposed law, the Irish legislation rests on a murky definition of hate. But Ireland’s Justice Minister Helen McEntee sees this lack of clarity as a strength. “On the strong advice of the Office of the Attorney General, we have not sought to limit the definition of the widely understood concept of ‘hatred’ beyond its ordinary and everyday meaning,” she explained. “I am advised that defining it further at this juncture could risk prosecutions collapsing and victims being denied justice.”

12. At Front Porch Republic, Nadya Williams has some opinions that are not . . . sheepish. From the piece:

That we are not an agrarian society is reflected in how we speak of sheep, that quintessential antithesis of leaders. Sheep are not interested in leading but are dreaming of a quiet rooted life. When used to describe Jesus’ followers in the New Testament and in the early church, the term “sheep” was originally one of endearment and beautiful tenderness in an otherwise brutal world. It readily brings to mind the image of the Good Shepherd in early Christian art—Jesus carrying a lamb upon His shoulders. It is a picture of unconditional love—of a shepherd willing to search for his lost sheep high and low in the night, willing to carry a hurt sheep even while bent down from the weight and exhaustion, willing, ultimately, to die for the sheep. This image also reveals the worth of sheep: they are, to their shepherd, a priceless treasure. Not one shall be lost.

We have come a long way since. Today, to call someone a sheep is more often than not used as an insult. To be a sheep is to be an intellectual lightweight, unwilling to think for oneself, likely to follow blindly to one’s doom. In Nancy Shaw’s bestselling children’s book series, sheep drive a jeep, sail a ship, go out to lunch, or take a hike—all with hilariously disastrous results that exemplify the worst of what we think already about the intelligence level of sheep. “Uh oh, the jeep won’t go.” Indeed.

Yet let us consider a simple mathematical truth that applies to every organization: the sheep must outnumber the shepherds. Followers must be many, whereas leaders are generally quite few. At any given moment, there is only one president of a country or corporation or university, just one mayor of a town, just one lead pastor of a church. And so, we face a mathematical conundrum. There are too many who wish to be shepherds instead of sheep.

Lucky 13. At National Review, Andrew Walker claims that journalism has a religion problem. From the article:

Which brings me to the purpose of this essay: Journalism has a religion problem. More specifically, journalists are either unaware or unwilling to admit that their own views, presumably untouched by “religion,” are nonetheless passionately held convictions grounded, well, somewhere. What do I mean by that? Well, journalism that touches on religion and politics tends to see religious viewpoints as carrying a special burden. It goes something like this: “Tell me, Mr. Pious, why a diverse population should accept your views on morality, considering they come from religion.”

I’ve had two interactions like this myself when speaking with journalists about religion, politics, and ethics. For example, I was once asked why it would be okay for a Christian florist to decline making flowers for a same-sex wedding. I was asked, “Is that not imposing someone’s religious values on someone else?” I recall telling this journalist, “Well, the florist’s views are surely grounded in religion, but her views about marriage are not exclusively religious. This is a debate about what marriage is, not whether my religious claim is accurate or immediately relevant to the conflict at hand. In effect, this is a debate about a moral good that surely is grounded in theological realities from my perspective, but not limited to theological realities alone.” The crux of the issue, however, is that because the reporter saw a bright “religion” sign hanging over my head, she used that to force her own biases about secular neutrality on me. She did not see that her secular viewpoint about gay marriage was an imposition on me, though it was. As these types of debates get framed, it was okay for the florist to have her conscience mocked and punished. What could not happen was expecting the same-sex couple to act like adults and patronize a different florist in the marketplace, one that had no scruples about arranging flowers for a same-sex wedding.

Bonus. At The Spectator, Bill Kauffman tells of a friend whose hobby is visiting the graves of dead presidents, veeps, and other hifalutin solons. From the piece:

He took up his hobby in earnest in 1996 with visits to New Yorkers Martin Van Buren (Kinderhook) and Chester Arthur (Albany). He and his wife Peggy, Pat’s equal in brio, cheer and uproarious good humor, have since crisscrossed America, knocking off Oval Ones and second bananas and also-rans, typically on side trips from Kiwanis conventions.

As his target list of electoral-vote winners and losers shrank, Pat added New York governors. He’s notched forty-five of the fifty-three and expects to nab about half of the holdouts, including Mario Cuomo, on an upcoming trek to the Vampire City.

In a fit of madness Pat once considered canvassing every deceased cabinet member, but he regained his senses, and so he has yet to make the acquaintance of commerce secretaries Luther Hodges (Eden, North Carolina) and Frederick Mueller (Grand Rapids, Michigan).

The grandest and gaudiest memorials, opines Pat, are dedicated to assassinated Buckeyes Garfield and McKinley, and the most modest (and out-of-the-way) is Calvin Coolidge’s humble stone in Plymouth, Vermont. (“You’d never know it was his other than the presidential seal.”)

For the Good of the Cause

Uno. At Philanthropy Daily, James Davenport nails it: Fundraising worker bees need to speak clearly and consistently about a nonprofit’s mission. Download the wisdom here.

Due. Save those dates! October 23-24. And mark the location! Pepperdine University in Malibu, CA. Why? Because that’s when and where the Center for Civil Society will be hosting its 2024 Givers, Doers, & Thinkers conference, this one on “K to Campus: How the Education Reform Movement Can Reshape Higher Ed.” Agenda and speakers will be announced soon, but registering, getting info, and all such stuff can be done and found right here.

Department of Bad Jokes

Q: What did Caesar do at the wedding reception?

A: He came, he saw, he conga’d.

A Dios

Oh, you simply have to love the lore, that Saint Brendan the Navigator and his band of Celtic monks, bounding on the sea some time in the sixth century, saw an island and came ashore in order to say a Mass, and then the island—which in fact was no island, as it had a blow hole—moved, which is what whales are apt to do when candles are being burned on their backs, so the monks skedaddled back to their boat, and continued their seafaring, it is claimed maybe even on to the Americas. And it’s true, at least the part about the whale and the Mass: Someone even took a photo!

May We Enjoy the Garden, Sprung in Completeness Where His Feet Pass,

Jack Fowler, who may get a dispensation and knock a few back while waiting for emails at jfowler@amphil.com.