As goes the popular carol, on this chilly night a Good King spied a poor man gathering wood, flexed his charity, and made himself an inspiration.

There is no going to the videotape, the event in question having occurred (or did it?!) over a millennium ago, so—for argument’s sake, and maybe for our souls’ sake—we shall go to the carol:

Good King Wenceslas looked out,

on the Feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about,

deep and crisp and even;

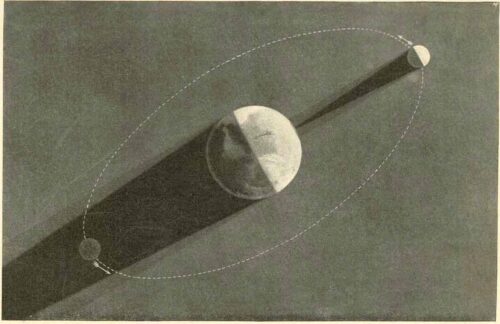

Brightly shone the moon that night,

tho’ the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight,

gath’ring winter fuel.

Just who was this night-peeping Good King, and why was he so animated on that 26th of December, a day of Christendom honoring the faith’s first martyr? And is this a ditty about a contrived legend, a fabled invention, an imagination figment rooted in some medieval monk’s incense-induced hagiography—or does the tune tell of a true royal who, by largely trustworthy accounts, was good (saintly even!), and a man of determined charitable efforts?

It seems the latter. About the Good King: His name at birth was Vaclav, this Bohemian better known as Wenceslas, or sometimes “Wenceslaus,” and of centuries-spanning importance to Christianity, Christmas, the Czech people, Victorian England, Middle-Age rules for royal demeanor, and charity in action.

Born in Prague in 907, when barely a teen Wenceslas assumed (in name) youthful leadership of Bohemia upon the death (in 921) of his father, Vratislaus, husband of the scheming Drahomíra—who, according to the original 1750’s edition of Butler’s Lives of the Saints, was a “hard and cruel pagan,” and a nasty daughter-in-law to boot: Drahomíra orchestrated the murder of her late husband’s mother, the pious Ludmila, martyred over her role as regent to the young Duke.

(Wenceslas was never a king in his lifetime; that rank was bestowed on him posthumously by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great, in admiration of his virtuous life.)

By all accounts, Ludmilla (a recognized saint) was a flop as a Catholic apostle to the still-pretty-paganish Bohemian people, but whatever her broader evangelical failures, her spirituality and teaching proved the central reason why her grandson, Wenceslas, led a life of piety and reverence, embracing his faith in defiance of maternal nastiness. With her husband dead and mother-in-law dispatched, Drahomíra assumed the coveted regent role, and led aggressive anti-Christian efforts that Wenceslas—allied with faithful nobles—undid when he turned 18 in 925.

As a leader, and as a man of faith, the Duke was no slouch. Per Butler:

Wenceslas meanwhile ruled as a brave and pious king, provided for all the needs of his people, and when his kingdom was attacked, overcame in single combat, by the sign of the cross, the leader of an invading army. In the service of God he was most constant, and planted with his own hands the wheat and grapes for the Holy Mass, at which he never failed daily to assist. His piety was the occasion of his death.

Other accounts describe Wenceslas’s innate holiness leading him to become an avowed virgin. Regardless, his faith, and demise, mirrored his grandmother’s: death, courtesy of a jealous family member. Again, per Butler:

Once, after a banquet at his brother's palace, to which he had been treacherously invited, he went, as was his wont at night, to pray before the tabernacle. There, at midnight on the feast of the Angels, 938, he received his crown of martyrdom, his brother dealing him the death-blow.

Yes, like mother, like brother: As if troubles with the murder-plotting Drahomíra hadn’t proved bad enough, Wenceslas’s only brother, Boleslaus, channeling mom’s proclivity to jealousy, arranged for the ruling Duke to meet with martyrdom. A mid-1950s revised and updated version of Butler cast the Duke’s final days thus:

In September 929 Wenceslaus was invited by Boleslaus to go to Stara Boleslay to celebrate the feast of its patron saints Cosmas and Damian. On the evening of the festival, after the celebrations were over, Wenceslaus was warned he was in danger. He refused to take any notice. He proposed to the assembly in the hall a toast in honour of “St Michael, whom we pray to guide us to peace and eternal joy", said his prayers, and went to bed. Early the next morning, as Wenceslaus made his way to Mass, he met Boleslaus and stopped to thank him for his hospitality.

"Yesterday," was the reply, "I did my best to serve you fittingly, but this must be my service today," and he struck him.

The brothers closed and struggled; whereupon friends of Boleslaus ran up and killed Wenceslaus, who murmured as he fell at the chapel door, " Brother, may God forgive you "

At once the young prince was acclaimed by the people as a martyr (though it seems that his murder was only very indirectly on account of religion), and at least by the year 984 his feast was being observed. Boleslaus, frightened at the reputation of many miracles wrought at his brother's tomb, caused the body to be translated to the church of St Vitus at Prague three years after his death.

The shrine became a place of pilgrimage, and at the beginning of the eleventh century St. Wenceslaus, Svaty Vaclav, was already regarded as the patron saint of the Bohemian people; and as the patron of modern Czechoslovakia devotion to him has sometimes been very highly charged with nationalist feeling.

Wenceslas never lost popularity, which intensified in the immediate aftermath of his death, and thrived over decades, then centuries. Several accounts of his life were written in the years ensuing his death. In her research for Hastening Toward Prague: Power and Society in the Medieval Czech Lands, author Lisa Wolverton recounts a 12th-century hagiographic depiction of the popular martyr that relishes his charitable doings:

As is read in his Passion, no one doubts that, rising every night from his noble bed, with bare feet and only one chamberlain, he went around to God’s churches and gave alms generously to widows, orphans, those in prison and afflicted by every difficulty, so much so that he was considered, not a prince, but the father of all the wretched.

Of interest: The charitable legend became fact, at least to one future religious leader. Enea Silvio Piccolomini, a 15th-century church ambassador and bishop—and the man soon to become Pope Pius II—declared in his Historia Bohemica that the snow-traipsing story of Wenceslas helping the poor was indeed true.

And as the cult of Wenceslas deepened (it remains important: Saint Wenceslas’s feast day, September 28th, is the premier national holiday in the Czech Republic) the legend spread beyond Bohemia and its neighboring regions, becoming prominent in, of all places, England, so much so that the Central European Catholic saint’s story of do-goodery has even adorned various seasonal postage stamps of the United Kingdom.

And, of course, the story became the subject of one of Victorian England’s great carols. How did that come to pass?

Credit for this must go to John Mason Neale, a mid-19th century minister, hymn writer, and author who wedded the story of Wenceslas—a tale included in his 1849 collection Deeds of Faith: Stories for Children from Church History—to a sweet 13th-century Finnish tune, Tempus Adest Floridum (a hymn originally about Easter.). Thought lambasted by music critics and purists, “Good King Wenceslas” and its lovely tale of royal humility and charity nonetheless proved immensely popular with English commoner, and remains a central cultural touchstone for Christmas carolers, who love to belt out:

Good King Wenceslas looked out

On the feast of Stephen

When the snow lay round about

Deep and crisp and even

Brightly shone the moon that night

Though the frost was cruel

When a poor man came in sight

Gath'ring winter fuel

"Hither, page, and stand by me

If thou knows it telling:

Yonder peasant, who is he?

Where and what his dwelling?"

"Sire, he lives a good league hence

Underneath the mountain

Right against the forest fence

By Saint Agnes' fountain"

"Bring me flesh and bring me wine

Bring me pine logs hither

Thou and I will see him dine

When we bear the thither"

Page and monarch, forth they went

Forth they went together

Through the rude wind's wild lament

And the bitter weather.

"Sire, the night is darker now

And the wind blows stronger

Fails my heart, I know not how

I can go no longer"

"Ark my footsteps, my good page

Tread thou in them boldly

Thou shalt find the winter's rage

Freeze thy blood less coldly"

In his master's step he trod

Where the snow lay dented

Heat was in the very sod

Which the saint had printed

Therefore, Christian men, be sure

Wealth or rank possessing

Ye who now will bless the poor

Shall yourselves find blessing

It’s a wonderful tune, a wonderful story, yes. But “Good King Wenceslas” should also be considered an important lesson, one to be recalled not only on this day, the Feast of Stephen, but on all days, especially in a society where philanthropy obsesses not on poor men coming into sight but on Big Fixes to Big Problems usually Far Away and requiring Metric Analysis.

Sometimes, small problems can be spied outside our very window, and call on us to choose to “bless the poor.” Or not.

May we recommend on this, also the Second Day of Christmas, also Boxing Day, whose roots are in charity towards the poor, that—whatever day we may be confronted with an opportunity to immediate and present charity—the choice opted for will be the one which results in finding blessing?