Dear Intelligent American,

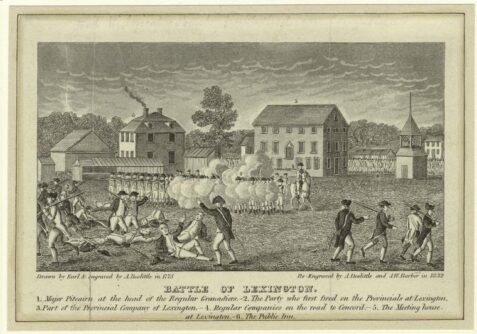

Formal independence proceedings for our Republic commenced on June 7th, 1776, when Richard Henry Lee, Virginia Delegate to the Second Continental Congress, offered the following motion:

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

It took a few weeks for delegates to reach Philadelphia—the Acela train having broken down—to debate the motion, form committees (one to draft a Declaration), and return from respective colonies with guidance from their legislative peeps. On July 2nd, Lee’s motion came up for a vote—it was approved unanimously.

Hail thee, festival day! Well, not so fast: The 2nd was about to come in second, despite the wishes of John Adams, the great man of Massachusetts, who wrote his wife Abigail:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.—I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

Cue the Womp Womp sound effect: Sorry, John, your apt detector needed recalibrating, because it was July 4th, when the sexier Declaration of Independence was approved, that immediately earned history’s Epocha distinction. Still, we thank you for the recommendation of illuminations—that one stuck.

Speaking of illumination, some of the following recommendations will surely offer such.

To Quote the Great Mister Sullivan, Tonight, We’ve Got a Really Big Shew

1. At The American Mind, fan favorite Daniel J. Mahoney penetrates the Ukrainian Tragedy. From the essay:

In truth, Solzhenitsyn represents a fundamental example for the future of a decent Russia: an unwavering defense of conscience and human dignity, an adamant refusal to conflate the best of historic Russia with crude authoritarianism or soul-destroying totalitarianism, a humane, moderate, and self-limiting nationalism or patriotism, and a desire for equitable dealings between Russia and Ukraine. Extreme Ukrainian nationalists hated him and all things Russian. But he never reciprocated such hatred.

In the third volume of The Gulag Archipelago, the great Russian writer lambasted his fellow Russians for turning a blind eye to legitimate Ukrainian grievances over the centuries. He believed Ukraine should be free to go its own way but not with unjust “Leninist” borders left over from the Soviet period. In Rebuilding Russia, Solzhenitsyn eloquently reminded his Ukrainian interlocutors that both the Ukrainian and Russian peoples were victims of an inhuman ideology built on the twin foundation of violence and mendacity. Famine, terror, and collectivization afflicted both great peoples, even if Ukrainians suffered particularly cruelly in 1932 and 1933. Shared opposition to totalitarianism ought to shape and deepen common bonds built in suffering and a shared defense of human dignity. Like most Russians, Solzhenitsyn opposed indefinite NATO expansion (he died in 2008). But half-Russian and half-Ukrainian himself, he once wrote that “If, God forbid, there is war between Russia and Ukraine, I will have nothing to do with it, nor will I permit my sons to join.” Solzhenitsyn is a living reproach to the extreme nationalists on both sides: his repeated calls for “repentance and self-limitation” can perhaps challenge and modify the thinking of frenzied partisans.

2. More TAM: John Cohen takes on corporate philanthropy, a thing unfriendly to civil society. From the piece:

For nearly a century, corporations channeled their charitable giving through their respective foundations—an arrangement eventually formalized by Congress with the passage of the 1969 Tax Reform Act. Under the Act, which remains the law of the land today, corporate foundations receive many of the same tax benefits as public charities in exchange for abiding by certain standards of conduct and transparency. For example, unlike public charities, corporate foundations must disclose publicly in their annual IRS Form 990-PF filings the amounts, purposes, and recipients of their grants. They also must pay out five percent of the fair market value of their assets each year to qualifying recipients. Under no circumstances can corporate foundations mingle with or harness the business divisions, assets, or expertise of their parent companies, nor can they engage in political activities such as lobbying or electioneering.

None of this sits particularly well with today’s corporations, which hold more ambitious visions for society than their predecessors and have outgrown the benefits conferred by foundations. Companies across the country have shuttered or sidelined their foundations and relocated their philanthropic activities in-house. This enables them to leverage their business assets and expertise to maximize their effect on society, engage in politics, lobbying, and for-profit philanthropic schemes without incurring the wrath of the IRS, and, importantly, avoid disclosing any such activities to their shareholders or the public at large, shielding them from criticism.

3. At Law & Liberty, Richard Reinsch makes the case for the wisdom of Frank Meyer on the vitality of a free economy as a bulwark against the aggrandized state. From the essay:

If these revolutionary forces were to be turned back, Meyer argues, then a “militant” and “conscious conservatism” is required. That conservatism will operate in a “revolutionary world.” As Meyer notes, the traditions we have known are “rapidly becoming—thanks to the prevailing intellectual climate, thanks to the schools, thanks to the outpourings of all the agencies that mold opinion and belief—the tradition of a positivism scornful of truth and virtue.” Perhaps the conflict, then and now, remains fundamentally one between statism enlisted on behalf of collectivist ideology which sees no limits to power versus the dignity of the human person which requires for its protection, the division of power, the limitation of government, and the freedom of the economy. In short, “What is at stake are fundamental concepts of the relationship of individual men to a society and the institutions of a society.”

If we are in a revolutionary moment, can we afford the luxury of a free economy? Meyer asked the following question: “What is the decisive virtue of a free economy?” The answer, Meyer declares, is its limitation on the power of the state. From this we can build other reasons: the individual person—the consumer—possesses fundamental power as to what should or should not be produced. From this has resulted the conditions for the incredible growth in productivity and ingenuity in the last two centuries. However, the freedom of the consumer, investor, and worker is primarily built on the limitation of state power from controlling human life.

The free economy itself cannot guarantee a good and virtuous life, Meyer states. But it is necessary for the preservation of freedom, which is the condition of a virtuous society.

4. At The Bitter Southerner, Jeremy Jones pays tribute to his late grandfather, an extraordinarily ordinary man. From the remembrance:

“Would you write your papaw’s obituary?” she asked, ever practical even amid the loss of the love of her life.

There was plenty to tell. He’d stolen a school bus as a teenager and backed it over a teacher’s car. He’d been shipped to Germany with the Army in 1950, where he flew up the ranks despite accidentally firing artillery through an empty house. He’d led the union at the textile mill where he worked most of his life. But he never talked much about any of that. What he set out to do was build a small life in Fruitland, North Carolina, to raise up his daughters and do the dishes and fix the broken garage door. He set out to live quietly—and then pass away just the same.

When I sat down to write, I found myself dropping details into a template—son of, survived by. The obituary form puts a particular pressure on what matters, on what should be remembered and praised, but what does one say about a life that aimed to carry on in the background, that had no interest in a name in newsprint or an award on the mantel? Ray Harrell, son of Jim and Cora, was content to sit still and watch the breeze scatter the leaves? Ray Harrell, sergeant first class, arranged the bills in his wallet in descending order? Ray Harrell, survived by Grace, whistled the same invented tune year after year while searching for the right nail in the shed? I filled in the expected details and sent the obituary to the newspaper, but I knew it wasn’t right. It captured nothing of the life he lived. What I returned to in the days after he passed, as the ladies from church covered the table in casseroles and Grandma slept in a bed alone for the first time since she was 19, was the sheer audacity of a quiet life.

5. At National Review, Jay Nordlinger profiles a courageous Cuban writer, Abraham Jiménez Enoa. From the piece:

Jiménez Enoa and his friends decided to start an independent online magazine—El Estornudo. That name means “Sneeze.” How did they come up with it? They were wracking their brains, trying to think of a name. Then they heard a man in the street selling lemons and honey. “Get some lemons and honey, so you don’t have to sneeze!” In Cuba, people consume lemons and honey when they have a cold. It’s like a home remedy. Jiménez Enoa and his friends thought, “That’s it. A sneeze.”

A sneeze is an involuntary action, or reaction, something the body just does. You can’t control it. If I understand correctly, Jiménez Enoa & Co. thought they could do no other—no other than to speak the truth, as they saw it around them, in an independent journal.

The government blocked it, of course. They made it impossible for Cubans to gain access to it—or almost impossible, because some people used VPNs and other devices to get around the censorship.

The government did a lot worse than block the magazine: They made the lives of Jiménez Enoa and other staffers hell—by arresting them, detaining them, interrogating them, spying on them, carrying out various retaliations against their friends and family.

On one terrible day, state agents seized Jiménez Enoa and stripped him of his clothes. They put handcuffs on him and forced his head between his feet. They filmed him and mocked him. They threatened to imprison him and destroy his family. This went on for hours.

6. At Comment Magazine, Christa Ballard Tooley reflects on The Troubles of Irish infamy. From the essay:

Ireland is often regarded as the first of England’s colonies. In the sixteenth century, England marked out plantations in the rich Irish soil, where English colonists were encouraged to settle and Irish inhabitants could pay for the privilege to labour. These plantations marked a change in English policy, from the attempted domination and elimination of Irish chieftains to the establishment of a new social hierarchy with the English at the top. From that time on, in Ireland as in other lands under imperial authority, the relationships that grew between ruling classes, settlers, and the population at large bore the taint of exploitation, seasoned with the personal familiarities of neighbours and fraught with more than the usual animosities. Over centuries, the blurred distinctions between statecraft and community craft shattered the mixed Irish-English population into identity fragments that came to appear primeval, and Irish-Catholic and English-Protestant emerged as ethnic rather than religious identities. By the time violence struck, and struck again in reprisal, the cycle had already come to seem inevitable.

The Troubles, which endured for thirty years and claimed more than 3,500 lives, brought to a head the long political and cultural struggle between neighbours in Northern Ireland: Catholics, who tended to identify as Irish, and Protestants, who tended to identify as British. The Irish Catholics who called themselves Republicans (or Nationalists) saw their cause as seeking civil rights for Catholics in a predominantly Protestant state, and paramilitary organizations like the IRA deemed themselves a revolutionary political movement fighting against an empire. The Northern Irish Protestants, however, did not see themselves as benefiting from imperial protection or privilege. Their argument for violence—threatened by the balaclava-clad men holding submachine guns over the street in the 1994 Shankill Road mural—found its legitimacy in the call to defend themselves and their communities. For Northern Irish Protestants of that time, the hostility of the world around them seemed to preclude their participation in peacemaking.

7. At Religion & Liberty Online, Marc Sidwell takes on the mantra that the British Empire was evil. From the piece:

Enter Professor Nigel Biggar, asking a disarmingly simple question: Is it true? His new book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, assesses the case against the British Empire. Rather than a narrative history, Biggar proceeds thematically, tackling each of the major accusations that are made in turn. These include Britain’s role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade as against its leadership of the anti-slavery movement; whether its economic policies were exploitative; and whether its use of violence was excessive.

Biggar’s approach is calm and measured, preferring factual historical enquiry to the “nuance-vaporising ideological apparatus” of more fashionable takes. It is also not merely a historical investigation but a moral one. As such it asks hard questions about responsibility and foreknowledge, refusing to accept that every terrible outcome is proof that someone is to blame. A theologian and ethicist by training, Biggar is well placed to help the reader confront the difficulties that emerge when we stop hunting for reasons to condemn and try to judge honestly.

The result, it should be said, is no celebration of empire as an unmitigated good. Biggar lays many evils at the feet of British colonialism, produced by a mix of culpable wrongdoing, unjust actions, and unintended harm.

8. At Brownstone Institute, David Thunder scolds the scientists who refused to provide honest data during a pandemic. From the beginning of the piece:

One of the remarkable features of these Covid years is the amount of misleading and downright false information emitted by “official” sources, most notably public health authorities, government-appointed regulators, and mainstream media. A part of me hankers after the times when I could trust my government and media in a time of crisis. But if I am honest with myself, I have to admit that I’d prefer to live uncomfortably in the truth than comfortably in a fantasy built for me by someone who does not have my best interests at heart.

As someone who turned on a daily basis to the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for updates on the Covid outbreak in February and March 2020, I was especially shocked and disappointed by the abysmal failure of authoritative bodies to impartially report the evidence bearing on masking, vaccinations, lockdowns, PCR testing, and other aspects of pandemic policy. My whole faith in the political, media, and scientific establishment, limited as it was, was shaken to the core.

We have been betrayed by the people charged with sharing the best available data and information with us in a time of crisis. We have been lied to and deceived about matters of life and death, such as the risk-benefit tradeoffs of the Covid vaccines, not only by the pharmaceutical industry, but by the people who occupy leading positions of public authority in our society.

9. At Tablet Magazine, Marjorie Perloff, Anschluss refugee, gives perspective on the charges by Ken Burns and Ruth Franklin that President Roosevelt flopped at saving European Jews. From the piece:

In this climate, it is not clear to me what Roosevelt could have done. True, the 27,370 visas made available to German nationals each year between 1939 and 1941 were not sufficient: Perhaps a more zealous president could have done more, but once war broke out, his hands were, in any case, tied. Thus Roosevelt’s policy was to win the war as quickly as possible so as to rescue its victims as soon as possible. It has been suggested that we could have bombed the train tracks or trains that took the Jews to the camps, but it’s not clear how many lives this would have really saved in the end. Not to mention that the camps in question were almost all in the East, and our armed forces were nowhere near them: It was the Russian zone.

I find shocking, in any case, the argument, made both by Burns and by Franklin, that, just as the Roosevelt administration didn’t do enough to save the Jews, so we are not doing enough now to help the immigrants on our Southern border. The Holocaust, in Burns’ scheme of things, was not unique: It must be understood as one of many holocausts. “The similarities between the persecution of Jews during the Holocaust,” writes Franklin, “and the contemporary treatment of undocumented immigrants in the United States are discomfiting.”

Discomfiting indeed but for whom? The Jews of Europe were not just oppressed or persecuted: They were systematically and openly murdered, not for anything they said or did–on the contrary, many tried to please their new would-be masters—but simply because their ethnicity of origin was Jewish. Period. And bear in mind that although Germany lost the war, Hitler was largely successful in his aim of getting rid of Europe’s Jews. In most of Europe today, Jews are almost extinct. In Germany, for example, the population is .03% Jewish as compared to 5.8% Muslim. Indeed, in today’s Europe, antisemitism flourishes without the actual presence of any Jews.

10. At Public Discourse, Ana Samuel lays out the various upsides of marital fidelity. From the essay:

Second, permanent marital partnerships accrue material and financial benefits. Faithfully married people are better off financially because they pool their resources, with no sharing with additional romantic partners.

They invest together in their own assets, savings, retirement accounts, and education. This investment includes the manual labor that goes unmonetized—time spent helping with children, chores, and upkeep of other material goods—rather than on outside partners unrelated to the primary home.

Married couples can also sign couple-exclusive contracts with confidence, taking advantage of longer-term opportunities including insurance policies, homeownership, and entrepreneurial endeavors.

Nonmonogamous couples, by contrast, experience greater financial confusion and struggle. Myriad questions about how to handle expenses will bring on stifling decision fatigue. In an open marriage, fights will emerge around who pays for what, lives where, and how much can be spent on new romantic pursuits.

Jealousy seems inevitable as partners spend money on outside relationships, making budgeting an emotional minefield. The instability of polyamorous relationships will preclude much long-term financial strategizing.

11. At Word on Fire, Michael Adams asks the question of old, What does it mean to be charitable? From the article:

A quick Google search for what charity is will provide a starting place full of predictable definitions. It means that we assist those in need, judge others favorably, and are kind and tolerant toward others. As predictable—and even accurate—as these definitions are, they are also dangerous. They are dangerous in the sense that they only provide a partial view of what it means to embody the virtue of charity while failing to capture the most critical part of it, God.

Looking now to the Catechism of the Catholic Church for some more guidance, we find a fuller definition. A charitable person is not someone who just cares for others, but someone who “love[s] God above all things for his own sake, and our neighbor as ourselves for the love of God.” So while a charitable person is someone who assists those in need, judges others favorably, and is kind and tolerant to others, there is more to it. As the definition states, a charitable person first and foremost loves God above all things. The charitable person understands that for this to be true, they must properly orient their lives and set God as the foundation and objective of their lives. We then see that the foundation of charity, and all virtues for that matter, must be God himself. Seeing as God is being itself, he not only embodies the virtues, but he is the virtues.

This approach to life is quite countercultural. Modern culture would say that you should aim to be a “good person” and stop there. With this new approach rooted in God, we find that only he is a sufficient aim, and we are no longer to aim for just being a “good person” but a person likened to him. When we fail to orient our sights properly as the Lord calls us, we fail to aim at anything substantial and end up with a skewed view of what it means to be charitable. God is the origin, source, and foundation not only for charity but all virtues. If the definitions of virtues are stripped of God, we are left to perish in the subjective wasteland of modernity.

12. At the Marinette, WI, Eagle Herald, Erin Noha reports on a fundraiser that’s wrapped in bacon. From the beginning of the article:

“Who doesn’t like bacon? Nobody,” said Kathy Scoggins, executive director of the Harbors Retirement Community.

Their inaugural fundraiser, called “A Taste of Bacon,” from 4:30 to 7 p.m. on Tuesday at Marinette Elks Lodge, 430 Bridge St., Marinette, will go all in on its theme, with meaty morsels that span from BLT soup to butterscotch and bacon truffles, bacon pimento cheese, bacon candy and bacon butter. . . .

All proceeds will be split between funding for Spies Public Library and A Place for Max, an adult care facility.

Lucky 13. At The Imaginative Conservative, Joseph Pearce reminds all of the profound acting chops, and life, of Alec Guinness. From the piece:

Sir Alec’s first film roles found him switching from Shakespeare to Dickens. He appeared in Great Expectations in 1946 and Oliver Twist in 1948, his performance as Fagin in the latter being a triumph. Both these films were directed by David Lean, beginning a fruitful collaboration. Other Lean-directed films in which Sir Alec appeared were Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, A Passage to India and most especially The Bridge Over the River Kwai, for which he won both the Academy Award and the BAFTA Award for best actor.

Apart from the gravitas exhibited in these Lean-directed roles, Sir Alec also showed a great gift for levitas in several successful comedies produced by the London-based Ealing studios between 1949 and 1957, including The Lavender Hill Mob, for which he received his first Academy Award nomination, and Kind Hearts and Coronets, in which he played no fewer than nine different characters.

One of the most intriguing of the Ealing Comedies in which Sir Alec starred is The Man in the White Suit in which he plays a scientist who invents what appears to be an indestructible fibre. The film, beneath the rambunctious surface, is a powerful political satire in which capitalist factory owners unite with their erstwhile socialist enemies to prevent a new technology which would potentially be bad for business and for the livelihood of workers. Watching the film today, from the perspective of our technophilic culture, provides a techno-skeptical counterpoint to the contemporary optimism of scientism and suggests a “third-way” approach to political and economic problems beyond myopic Marxism and laissez-faire libertinism. Released in 1951, in the looming presence of the Cold War and the Bomb, The Man in the White Suit is a manifestation in comic form of the gritty Orwellian realism of the post-war years which transcended socialist-versus-capitalist reductionism.

BONUS: At Claremont Review of Books, Wilfred McClay considers John K. Lauck’s The Good Country, and wonders what has become of regionalism. From the review:

Sectionalism has been one of the great themes of American history, and the interplay among America’s urban, rural, and regional cultures has long been one of the most interesting factors in our national life. But the flattening and homogenization of the country over the course of the 20th century has rendered this aspect of our national life less and less visible, and hence less vibrant. The steady decline of genuinely independent regional and local newspapers and other news outlets is but one sign of this loss. Another is the fading interest in savoring the particularities of place: history, geography, culture, food, climate, local business, anything that distinguishes one locale from another.

No section of the country has suffered more from this process of national homogenization and stereotyping than the Midwest, as Jon K. Lauck well knows. An adjunct professor of history and political science at the University of South Dakota, he is the founding president of the Midwestern History Association and the editor of the Middle West Review, a journal dedicated to the study of the American Midwest. In addition, he is the author of several books, including The Lost Region: Toward a Revival of Midwestern History (2013), From Warm Center to Ragged Edge: The Erosion of Midwestern Literary and Historical Regionalism, 1920–1965 (2017), and his latest, The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800–1900.

Over a century ago, well before the onset of economic woes that caused the region to decline in recent years, the Midwest found itself on the receiving end of a steady flow of cultural disdain, whose principal target was that characteristic Midwestern settlement, the small town. “The Revolt from the Village” was the name given this literary and cultural moment by Carl Van Doren in his 1921 study, The American Novel, and examples of his thesis were plentiful and close at hand. Edgar Lee Masters’s 1915 book, Spoon River Anthology, a collection of autobiographical epitaphs from a small-town cemetery, evoked the acrid hypocrisy and repression of the small-town environment. Similarly, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) sought to uncover what Van Doren called the “buried and pitiful” lives of its inhabitants. Ernest Hemingway complained of his childhood home, Oak Park, Illinois, that it was a place with “broad lawns and narrow minds.”

For the Good of the Order

Uno. At Philanthropy Daily, Elaina Bals scores the new “Faith and Freedom Index” produced by Napa Legal. Read the story here.

Due. Scotch Talks is back, baby, and you and your tumbler—filled with ice and some enervating libation (black sambuca!), or maybe a cold glass of milk if that’s your happy place—are all you need to bring to the free webinar, hosted by AmPhil bossman Jeremy Beer, who will be joined by aces Therese Beigel and Mark Diggs – the trio there to learn ya some tried-and-true methods that will make your nonprofit’s direct-response program rock. It takes place (via Zoom) on Thursday, July 20th, from 3:00 to 4:00 p.m., Eastern. How’s about you belly up to the registration page and . . . register? Do that right here.

Tre. You think maybe that America’s skyrocketing irreligiosity has something to do with the problems affecting this nation? This critical issue demands your attention. Show it at the forthcoming C4CS conference—“Rise of the Nones: How Declining Religious Affiliation Is Changing Civil Society.” It takes place on November 7–8 in glorious Scottsdale, AZ. Get complete information, right here.

Department of Bad Jokes

Q: Why did the worker get fired from the M&M factory?

A: Because he kept throwing away the W’s.

A Dios

There seem to be so many fewer birds than when Yours Truly was being raised in the Bronx—the sparrow, once so prevalent, is MIA. The story of what and why makes one despondent. It came to mind today because of Sunday’s gospel reading, from Matthew: “Aren’t two sparrows sold for an assarion coin? Not one of them falls on the ground apart from your Father’s will.” The omniscience of the Creator is unfathomable. May His knowledge include the fact that we will soon see more wing-ed friends in our communities.

May the Snare of the Fowler Never Capture You,

Jack Fowler, who can be snared at—and even sneered at—at jfowler@amphil.com.

P.S. Hmmm . . . on second thought, maybe, after all, it was a ‘Rilly Big Shoo,’ eh?