Dear Intelligent American,

Lent commences this year on Valentine’s Day, so for some, constrained by the ancient Ash Wednesday rules of fasting and abstinence, the Whitman’s Samplers and the romantic dinner will have to wait. And so will commence six weeks of . . . repentance? Hardly! After all, that’s a tough thing to pray for or seek, since we live in a time when no one seems to have ever done anything that merits remorse or regret.

So he said, sarcastically.

Whatever the absolution right that is part and parcel of this era of victimhood, the coming weeks offer a refresher to those who have ears and hear, eyes and see. Because the real after all is told in Mark: that Jesus “summoned the Twelve and began to send them out two by two . . . So they went off and preached repentance.”

Sermon over. Before the excerpts and links come front and center shortly, three things. The first: It being Black History month, and Your Humble Correspondent fancying himself a recommender of classic movies, do watch the original (1951) version of Cry the Beloved Country. You might even find in it a powerful message of . . . repentance.

The second: There is this very cool webinar coming up on February 15th (sponsored by Innovest and the Christian Employers Alliance) titled “Three Areas Where Your Business—and Religious Freedoms—Are Most Vulnerable.” It will feature leaders in the healthcare, investment, and donor relation sectors discussing why accountability in these three industries is imperative to protecting religious freedoms. It’s free, goes from 12:00 to 1:00 p.m. (Eastern), and is a must for anyone who cares about religious liberty. Sign up here.

Finalmente, but not least: That greatest of amigos and true public intellectual, David Bahnsen, celebrates this week the formal publication of his new book, Full-Time: Work and the Meaning of Life. Get yourself a copy and learn why it is in work that we find meaning and purpose in helping cultivate God’s created world.

Do Read These Before Donning the Sackcloth and Ashes

1. At The American Conservative, Nate Hochman laments the return of comedian Jon Stewart to his old “Daily Show” haunt—the reason being that he just ain’t funny. From the piece:

Nostalgia may be all that Stewart has left to offer. Since he left the Daily Show in 2015, the political comedian has been in the wilderness. The year he left his former post at Comedy Central, he signed a four-year deal to produce digital cartoons featuring his voice with HBO; the project was scrapped after two. With two years left on the contract, he announced that he would be doing two stand-up comedy specials—neither of which ever materialized. His foray into directing resulted in 2020’s Irresistible, a political comedy that returned less than $500,000 at the box office. In 2021, he premiered The Problem With Jon Stewart on Apple TV+; by the fifth episode, the show’s viewership had tanked by 78 percent, pulling in 20 times fewer eyeballs than Late Week Tonight with John Oliver. The show was canceled after two seasons, reportedly due to “creative differences.” . . .

The more salient reason for Stewart’s decline is that he was a man born for—and shaped by—a particular place and time, and that the conditions that enabled his decade of success have long since departed. Stewart’s brand of smirking, needling, speaking-truth-to-power liberalism made a certain degree of sense in the Bush era, when there was at least a plausible case that the left was “anti-establishment.” (Or even that there could be such a thing as an “anti-establishment left” at all). His demeanor may not have endeared him to most conservatives, but it was charming to a certain genre of disaffected young liberal who felt alienated from the centers of power governing America at the turn of the century. In today’s context, however, Stewart’s schtick is worse than boring—it’s obnoxious.

2. At her blog, “Charlotte Was Both,” Amy Welborn laments the consequences and motivations of contemporary Church music. From the commentary:

I’m not here to ding on contemporary liturgical musicians, who are mostly well-intentioned people of faith who are giving of themselves, formed in particular style and approach that is presented to them as a given. As optimal, even. Looking to begin the Mass, what else would one do but sing You are Welcome Here? Well?

Here’s what struck me during and after this Mass, in a way that I’d never really thought about before. I thought about how the experience and understanding of faith is potentially affected by the replacement of the deep tradition of Catholic sacred music with contemporary material.

It’s not about “reverence” as it is about an experience of faith that reflects, not the deep Tradition that is expressed in Catholic sacred music, but the ideas of some guy who happen to write a piece that some company liked, bought and then sold this parish the rights to sing. . . .

As I have written before, it is one more expression of the determination to see the Church’s deep tradition as a barrier, not a door or window. As an example of the conviction that our call is to express the unique Spirit in the present moment in our unique community—which almost always ends up being the expressions designed and controlled by a few. A liturgy that “reflects the local community,” for example is going to be little more than a liturgy that really “reflects the tastes of the people in charge.”

3. At The Lamp, Helen Andrews goes tongs and hammer at “H.R.” From the essay:

The wedge that H.R. used to shove its way into the American workplace was anti-discrimination law. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was not just a new law but a new type of law, a bigger revolution than anything passed during the New Deal. Before, business regulation had been categorical: you may not hire workers under x years of age or force them to work more than y hours in a day. Violations were easy to determine; they were straightforward questions of fact. With the Civil Rights Act, for the first time in the legal history of the Anglosphere, regulation sought to scrutinize a boss’s motivations. Whether an act was lawful or not depended on whether the reasons behind it were pure.

In retrospect, it is odd that personnel departments were the site of growth in response to anti-discrimination law. If you want to know whether your business is in compliance with the law, typically you ask a lawyer. But as the Harvard sociologist Frank Dobbin explains, lawyers were “unwilling to recommend compliance strategies not yet vetted by judges. Professional norms directed them to advise clients about black letter law and not to speculate wildly about what the courts might or might not approve.” Personnel departments, having no such inhibitions, filled the vacuum.

Another musty old legal tradition upended by the civil rights revolution was the presumption of innocence. In an anti-discrimination lawsuit, if a plaintiff can make a prima facie case that some demographic is underrepresented in a company’s workforce—a matter of bare statistics, which doesn’t necessarily imply any ill will or bias—the burden of proof shifts to the employer, who now has to prove that the disparity has an innocent explanation. An employer’s investment in diversity programs could go a long way in convincing a judge of his good intentions. In this new regulatory paradigm, doing the bare minimum to comply with the law was not enough. Employers were forced to compete with one another to demonstrate their commitment to diversity. This was a license for H.R. departments to let their imaginations run wild.

4. At the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, Walt Gardner argues that the time has come for colleges to pay property taxes. From the commentary:

Then there is the difference between private and public colleges and universities where real estate is concerned. With the exception of the University of California and the State University of New York, most public universities and colleges own less land than private ones. Why should one sector be treated differently than the other in taxation? It has been argued that public institutions deserve different taxation simply on the basis of being public, but they create a burden on police and fire (for example) that is just as heavy as their private counterparts.

Finally, it’s hard to distinguish between higher education’s commercial activities and its strictly educational ones. In North Carolina, many higher-education entities, both private and public, are engaged in land-use that is clearly commercial. For example, the Carolina Inn at Chapel Hill provides rooms for members of the UNC Board of Trustees, but it also rents out space for weddings and parties.

Or consider what is happening at Harvard University, which today is the largest landholder in nearby Allston, Mass. The land Harvard owns is not solely devoted to residence halls or science labs for students, as the Harvard Crimson has noted. It also contains hotels, for example, which have little to do with the university’s educational mission. Yet Harvard’s real estate is exempt from property taxes. To placate Allston residents, Harvard has designed its own PILOT program, which donates $25 million to the Alston-Brighton Affordable Housing Fund. But the amount is a pittance compared with what the university would have to pay if its exemption were abolished.

5. More College Dollars: At Tablet Magazine, Tony Badran explains why America’s richest universities are protecting foreign students who are here to learn and to hate. From the article:

The scheme by which U.S. taxpayers pay to give 25% or more of the places at America’s most prestigious universities to foreign students is a recent innovation—one that took shape between 2004 and 2014, and has helped make the universities’ DEI rhetoric cost-free. The international share of freshmen at Georgetown nearly quadrupled from 3% in 2004 to 11% a decade later, with similar numbers at Berkeley and Yale. The growth in undergraduate enrollment at Yale during that decade was fueled almost entirely by foreigners. In that same period, the number of incoming foreign students at Ivy League schools rose by 46%.

Behind this increase lies the simple reality that only a comparatively small number of Americans can afford the mind-numbingly high fees that American universities extort from their captive domestic market. Foreign students, the overwhelming majority of whom are either the children of wealthy foreign elites or directly sponsored by their governments, represent a serious source of funding for American colleges, public and private alike. These students often pay full or near-full tuition and board, and help public universities balance the books in the face of budget cuts. More broadly, they augment revenue by helping to fill federally funded programs that are based on racial and ethnic quotas.

Depending on how you look at it, American universities have made either an exceedingly clever or else exceedingly reprehensible bargain: Quota-filling at a profit. While this practice is generally covered with asinine bureaucratic language such as “promoting diversity” and “fostering a cosmopolitan culture” for a “global community,” it is in fact a racket by which universities take slots presumably intended for members of groups that are held to be economically and culturally deprived—and on which the universities would be obligated to take a loss—and instead sell them at a profit to the families of some of the more privileged people on Earth, while also continuing to sell identity-politics platitudes as institutional ideology.

6. At Law & Liberty, Elizabeth Grace Matthew reflects on The Sopranos and the plight of the American male. From the essay:

When Tony mourns the obsolescence of Gary Cooper, he is lamenting the lack of moral clarity and self-control that he, despite all his cynicism, rightly idealizes as “American.” And when he glories in the majesty of St. Elzear’s, he is really grieving the patient upward mobility exemplified by his grandfather, who valorized honest work for modest rewards.

For Tony, Gary Cooper remains a symbol of American idealism and specifically “WASP,” nonethnic American folklore, just like St. Elzear’s remains a symbol of the uniquely immigrant work ethic. Thus, he can claim sufficient distance from each to profess disingenuous bewilderment about where these admirable touchstones have gone.

Because what really happened to Gary Cooper is that Tony failed to emulate him, and Carmela failed to raise him. Not because Cooper was white and Protestant, while they are arguably neither. And not because the virtues Cooper represents are old-fashioned.

It’s because the paths of least resistance—in this case, so-called toxic masculinity and the devouring motherhood that overcorrects for it—are always easier than those of delayed gratification and self-determination.

7. At The Spectator, Gavin Mortimer explains why Europe’s farmers are in revolt. From the piece:

Every two days in France a farmer commits suicide. Others walk away from the industry. In my département, there were 1,058 cattle farmers in 2014 and now there are 772. In the past two years fifty-four farms have ceased to operate.

My immediate neighbor, the cereal farmer, went organic a year ago. He is also disillusioned. He tells me that he feels as if he is more of a bureaucrat than a farmer, spending hours each week filling out forms and ticking boxes.

The revolt is not confined to France. All across the EU, farmers are rising up against their governments and, specifically, against Brussels. Spanish farmers have announced this week that they too will join the protest movement because of the “suffocating bureaucracy generated by European regulations,” and Belgian farmers are also mobilizing. The demonstrations began in the Netherlands in the fall of 2019 when more than 2,000 tractors drove to the Hague. There had been growing discontent at plans to restrict nitrogen emissions, but the catalyst for the tractor protest was the proposal by one left-wing member of parliament to halve livestock numbers. “Farmers and growers are sick of being painted as a ‘problem’ that needs a ‘solution,’” said Dirk Bruins, an industry spokesman.

8. At The Catholic Thing, H.W. Crocker III has a thing or two to say about heathenism, heathens, and living among them. From the piece:

Heathenism is popular because it idolizes the individual will, which to certain people—weak people, selfish people, people interested in money or power or simply themselves above all else—is quite intoxicating.

I use that word advisedly, because modern heathenism is obviously a form of drunkenness, of mental and moral impairment, that subverts logic, reason, and the recognition of the good, the beautiful, and the true (including the very idea of objective truth).

This is why today’s heathens are such bald-faced liars. It is why they promote a cult of ugliness in looks, speech, and action. It is why they are so furiously intolerant (not for them the biblical injunction to “Come now, and let us reason together” because there is no objective reality towards which we can reason together: it is simply my will—or “my truth” as they say today—versus yours).

And it is why even the most highly educated heathens—and many heathens are highly educated because the education system specifically rewards them and punishes Christian dissenters—can be so shockingly ignorant. Try asking a heathen, for instance, in what century the New Testament was written, or how he explains the Resurrection, or, of course, whether genocide against “colonialist” Israelis should be condemned, and you’ll likely get a lot of sophistical blather.

9. At Public Discourse, Megan Brand fiddles around with the idea of making communities via music. From the essay:

Orchestral music also provides a context for intergenerational relationships to form. During intermission at the concert we attended, the older people sitting behind us asked my daughters if they played instruments. Upon learning that they did, our older neighbors encouraged my daughters, reinforcing the idea that they can play with the orchestra too one day, if they practice well.

At the same time, my young daughters radiated a sense of joy and wonder that inspired the adults. As adults, we can easily overlook something majestic, as trials in life have dulled our senses to the beauty right in front of us. The social experiment in which the violin virtuoso Joshua Bell played his Stradivarius in plain clothes during rush hour in the D.C. metro makes this clear: of the thousand people who passed him that morning, children were the only demographic who uniformly noticed and paused to listen to the music. As the observing columnist summarized, “Every single time a child walked past, he or she tried to stop and watch. And every single time, a parent scooted the kid away.” Incredible music offers us childlike wonder and marvel, and children help us notice it in the first place.

Creating music is in itself a cooperative project, one that often involves members of different generations and demographics coming together to create a work of art. Classical music only works if everyone plays well together. Playing it requires us to listen to others; to tune our instruments to the same pitch; to submit to the same conductor to guide us on the music’s path; and, when unavoidable human error happens, to keep moving beyond our mistakes to join others where they are. In an orchestra, others depend on us, and we on them. The design is inherently community-building. In his creation myth, J. R. R. Tolkien used song to form worlds. His Silmarillion describes the transformation of nothingness this way: “The music and the echo of the music went out into the Void, and it was not void.” In Tolkien’s fantasy, as in real life, individual parts blend into harmonies, which in time reveal cherished communities.

10. At UnHerd, Nicholas Harris skins the Male Baldness Industrial Complex. From the (hair) piece:

Christopher had five hair transplants over a couple of decades, and the final one “took” completely, leaving him with a full head of hair. But he tells me about a friend who started losing his as a teenager. “I know that it destroyed his self-confidence,” Christopher says. The friend, now 70, neither treated nor shaved it, persisting with “combovers and things like that”. “He would say, ‘Once you go bald, your looks are gone and you’re always going to have to accept second-best in terms of a wife’. . . I know it ruined his life.”

In an age of technologically compelled self-obsession, a version of this fear is already filtering down to my own age group. Having barely achieved the quarter-century, friends are inspecting their family trees for evolutionary disadvantage, peeling back fringes to reveal widow’s peaks and Eiger foreheads. It is now more than common for my social reunions to begin with an update on the loosened thatch—stories of smoothing back your rug only to find yourself with furry fingers, and of showers that seem uncomfortably akin to shaves. These anecdotes find plenty of statistical company. A quarter of men who develop hereditary male baldness (“androgenic alopecia”) see symptoms before the age of 21; by 35, two-thirds of men have lost at least some of their hair.

Such is the potency of this fear that young men try to palliatively anticipate what’s to come. Ben is 29, and has been using medicinal treatments for hair loss for two years. “It was like a preventative thing,” he says. “I don’t like to think of myself as someone who is vain. But I don’t really exercise, and if I were to lose my hair, I’d basically just become my dad . . . It’s almost like a psychological thing where, if I take this pill, I’ll keep my hair. It’s like an anxiety deferred.” But he’s sure this is more prevalent among young men than it used to be. “If I was a 30-year-old man in the Seventies, and I was going bald, no one would care. Something has happened in the last 40 years.” And he’s right. For most of human history, however miserable it made them, men could do nothing about their condition. But now an entire male baldness industry has arisen to simultaneously nurture and service their fears.

11. At the North Tama Telegraph, Ruby McAllister reports that an Iowa fundraiser raised big bucks for the seesaw set. From the beginning of the piece:

A new inclusive playground at Dysart-Geneseo Elementary is $20,000 closer to becoming a reality thanks to a wildly successful Trivia Night fundraiser.

Held at the Dysart Community Building on the evening of Jan. 20, the fundraiser—organized by event chairs Amber Pippert and Dawn Stoakes with assistance from Aly Goken and Abby Adolphs, among others—served over 177 prime rib meals and sold tickets to more than two dozen trivia team tables.

Between event sales, donations, and live auction items, the fundraiser raised approximately $20,000 toward the playground project, DG Elementary Principal Derek Weber told the Telegraph last week.

12. At Plough Quarterly, Kirk Wareham finds that what he enjoys out back, behind the home, is a place that Nature has healed, as Nature is wont to do. From the piece:

But a few days later, I once again discovered that the wind and leaves had conspired to cover my path. Once more the rake was summoned and the path cleared. Only after this cycle had repeated itself several times did I notice an interesting thing: the leaves always accumulated in the top corner of each step, effectively softening the crisp, sharp lines that the shovel and I had created. Nature, it appeared, was attempting to erase my path and restore the hillside to its original form.

From a close neighbor, I learned that this wooded area was once an open cornfield. In the 1960s, the old-timer told me, a sand-and-gravel company had purchased the property and mined the living daylights out of it. By the time the company left, it had removed every tree and bush and plant from the entire area, along with some twenty feet of elevation. The fertile soil had been stripped away, leaving only a layer of sand and stone completely devoid of all vegetation. In the center of this barren landscape was a deep quarry with an odd hump in the middle.

Many years passed. Slowly the wounded land began the long process of healing. New soil developed, and grass and moss found a tentative foothold. As the years rolled by, nature continued to work her healing magic. Sturdy trees and lush plants emerged and flourished, and birds and other wildlife flooded in. By the time I arrived on the scene, all that was visible was a beautiful wooded nature sanctuary with a charming pond with a small island in the middle. . . .

This, then, is something that I have observed over the years. In many cases, nature is astonishingly quick and efficient at reclaiming a piece of herself that has been abused in some manner. Patiently she applies her healing balm to the rough places, blunting the sharp corners, softening the angles, smoothing the lines.

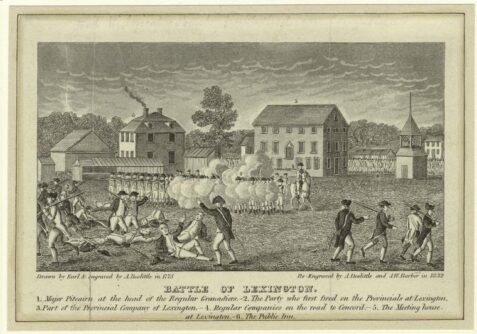

Lucky 13. At The Hedgehog Review, Charlie Riggs explains working on the Freedom Trail. From the piece:

The theoretical and practical challenges of giving a tour are as bracing as any an author faces in writing an essay. Tours are an art form, and like other art forms they involve—indeed thrive on—constraints. The puzzle is how to use one’s knowledge, storytelling ability, and personal charisma to unite the history one wants to describe with the concrete features and details of the modern cityscape. How does one use buildings, locations, views, statues, plaques, architectural features, and whatever else presents itself along the path in order to tell a story that moves forward chronologically, that maintains a relatively restricted cast of characters, and that varies in mood and dramaturgical effect?

Cities are palimpsests, their contemporary surfaces concealing, though not entirely effacing, their more remote past; they require skillful and creative interpreters. One of my favorite bits from my own Freedom Trail tour is a story I tell at the top of Spring Lane, across the street from an old brick building where there’s now a Chipotle Mexican Grill. That building, built in 1712, stands on the site of Anne Hutchinson’s home and once housed Ticknor and Fields, the great literary publishing house of the American Renaissance, which printed the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Louisa May Alcott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and others. Ticknor and Fields also operated a bookstore downstairs, the Old Corner Book Shop, that was a favorite haunt of many of these same nineteenth-century writers.

Bonus. At Discourse, Erec Smith proposes that deliberative rhetoric is essential for communal flourishing—and true abundance. From the essay:

Deliberation is especially important in a civil, pluralistic and free democracy, where “the people” ultimately in charge of the public good have widely different ideas about what that good should be. Therefore, “deliberative democracy” is the ideal system. Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson, political scientists and leading thinkers on the topic, define deliberative democracy as “a form of government in which free and equal citizens (and their representatives) justify decisions in a process in which they give one another reasons that are mutually acceptable and generally accessible, with the aim of reaching conclusions that are binding in the present on all citizens but open to challenge in the future.”

This kind of communication takes place in most civic, professional, educational and political contexts. From school board meetings to city council sessions to the floor of the U.S. Congress, deliberation is used to provide sound reasons for the efficacy of a policy and accept sound refutation from others until the deliberators reach a conclusion that is most advantageous to a community or society at large.

So, what does this have to do with abundance? If people have an idea that will provide the utmost abundance for themselves and others, they can better ensure its implementation if they are skilled in deliberative rhetoric. They can state their case to the local, state or even federal government. Theoretically, citizens with adequate skill in deliberation are more likely to acquire what they want than people who lack this skill.

For the Good of the Order

Uno. Even fundraising mavens need to be dispelled of prejudices about (against!) the value of direct mail marketing. Are you a maven? Or maybe simply a curious nonprofit worker bee determined to help your organization fund its mission? Whatever role you play, do join the Center for Civil Society next Thursday, February 15, from 3:00 to 4:00 p.m. (Eastern), via Zoom of course, for a free webinar—featuring AmPhil all-stars Austin Detwiler, Mark Diggs, and Therese Beigel—covering the ins and outs of direct mail marketing. Learn more and sign up right here.

Due. Speaking of consequential webinars, on Thursday, March 7, from 1:00 to 4:00 p.m., C4CS will be hosting a “Givers, Doers, & Thinkers” webinar on “Elements of Grant Writing.” This is a tried-and-true course that is heavy on the wisdom and tips—such as the common errors found in grant proposals (and how to avoid them). If you write grants for your nonprofit, or if no one in your shop does (but someone ought to) then attending this important “Master Class” is a must. Get complete information right here.

Tre. At Philanthropy Daily, Rebecca Houghton comes at us with the third and final part of her series on the role “deep work” plays in fundraising. Read it here.

Point of Personal Privilege

The son of Your Faithful Communicator is quite the writer, and at RealClearReligion celebrated Groundhog Day by celebrating Groundhog Day and reflecting on the Purgatorial plight that Phil Connors faced, and survived. Read it here.

Department of Bad Jokes

Q: Why did the banana go out with the prune on Valentine’s Day?

A: Because it couldn’t get a date.

A Dios

The intention in these parts is to fast this Lent. Is it possible to have an appetite for that?

May He Who Feeds the Sparrow Nourish Our Souls,

Jack Fowler, who entertains any and all missives sent to jfowler@amphil.com.