Dear Intelligent American,

Shakespeare and Frank Sinatra in their ways waxed about the essence of ring-a-ding-ding, the Bard thinking more about the embrace of love and the new season—which we now enjoy, after a weak winter. Yes, the voice of spring is in the air, just ask Señorita Cucaracha.

Sweet lovers may love the spring, but birds seem more fixed by the moment than ideas of amore. So hereabouts, one warmish afternoon last week, as winter was giving way, a bald eagle swooped low down this not-so-rural Connecticut street, while four vultures circled overhead, the aviary paths crisscrossing with a hawk who was being hectored by three crows.

Not the stuff of Hitchcock, but neither the stuff of an Avonian love ballad. Nor a scene to be espied on a typical New England afternoon.

Meanwhile, as the wings flapped above, crocuses were emerging nearby, and down the hill, the forsythia hedge gave off that tiny, initial, invigorating hint of yellow—both traditional signs of what the Avon Boy dubbed “the only pretty ring time.” Of that, you may be more familiar with Mr. Wonka’s expression.

Oh, and let us wish Front Porch Republic a very happy 15th Anniversary. Ding a ding, ding!

You Are on the Brink of Link, Don’t Shrink!

1. At New York Post, Christie Herrera offers practical advice on ways PO’d philanthropists can bring about changes at gone-woke colleges. From the article:

When a donor pulls a big gift from a college, the result is a brief news cycle.

If a donor directs that money to an advocacy group that criticizes the university’s failings, the result is ongoing pressure.

While some groups, like many free-speech organizations, are well-known, others fly under the radar. Philanthropists can also create or fund independent, school-specific organizations.

The goal shouldn’t simply be forcing out leaders in the short run. It should be fostering opposition on and off campus to demand real change over the long run.

That’s what donors want—the wholesale renewal of the colleges and universities they love and America needs.

2. At City Journal, Brian Eha considers the rise in big-city crime and how it renders America’s social fabric . . . threadbare. From the piece:

What does it do to us, living with chronic levels of high crime? Even in the worst neighborhoods, most residents are not criminals, yet in going about their lives they must breathe, like secondhand smoke, the noxious air of crime. An August 2021 meta-analysis of 63 studies pertaining to neighborhood crime and mental health, published in Social Science & Medicine, found crime “significantly linked to depression and psychological distress” among local residents. Importantly, it isn’t required that someone actually witness or fall prey to crime for its ubiquitous presence to affect them; according to researchers, neighborhood crime can be thought of as “the subjective perception of [residents] indicating danger or safety in their area.”

The anthropologist Sami Hermez has developed a concept he calls the “anticipation of violence.” Born out of research conducted in Lebanon in 2007, during months of intermittent bombings, his work describes how the ever-present threat of violence permeates local people’s awareness, alters social relations, and creates a way of life in which “violence is presented and implicated in the ordinary rather than the two being mutually exclusive.” Hermez is interested in war-ridden regions of the globe, where the normal warps under the weight of abnormal force. His concept holds true, however, for cities plagued by violent crime. Replace “war” with “crime” in his assertions and you get statements like: “everywhere the talk of crime seeps into daily conversations and decisions.” . . .

New Yorkers often feel crime more keenly than other Americans because many of us walk the streets and ride public transit, rather than traveling from home to office in two-ton, 200-horsepower bubbles, insulated from the reality outside. Murders in commuter cities may pass largely unnoticed by the citizenry, so long as the killings are confined to what academics call “micro-geographic units”—certain city blocks, sections of certain streets—possessing “criminogenic characteristics.” The baddest parts of bad neighborhoods. Domestic violence, gang beefs, internecine squabbles are hyperlocal affairs. Turf wars may be fought over tiny patches of sod.

Commercial Break!

The Center for Civil Society is holding an important webinar on Thursday, April 25, on “American Jews, Philanthropic Traditions, and Harsh New Realities.” Your Humble Correspondent will interview a trio of experts—Alexandra Rosenberg, senior director of development at Tikvah, Rebecca Sugar, author and longtime leader in Jewish philanthropic management, and Rabbi Rob Thomas, cybersecurity expert and philanthropist—about an ancient faith and its unique practices—and philosophy—of charity, conducted in and contributing to the tapestry of a country supposedly intolerant of intolerance, but now stained by repeated examples of elite antisemitism. You’ll want to register (the webinar is free, takes place, via Zoom, from 3:00 to 4:00 p.m., Eastern)—easily done right here.

Commercial Over!

3. At Claremont Review of Books, Charles Kesler assesses the competing brands of conservatisms, “National” and “American.” From the essay:

The political scientist Martin Diamond used to say that the oldest word in American politics is “new.” It ought not surprise, then, that today’s New Right is not the first, nor likely the last, that America will experience. The first proper or self-conscious modern conservative movement was the brainchild of William F. Buckley, Jr., among others, in the 1950s, and cast its first presidential votes for Barry Goldwater in the Republican primaries of 1960 and the election of 1964. Yet even that founding generation of American conservatives sometimes called itself the “New Right,” in contradistinction to the “Old Right,” whose anti-statist domestic policy had been crushed by Franklin D. Roosevelt in the “Revolution of 1932” (as Willmoore Kendall and Frank Meyer christened it) and whose non-interventionist foreign policy had been sunk by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. Yet the presence of other novel experiments in post-New Deal conservative thought, now largely forgotten, soon induced Buckley and his allies to begin referring to themselves also as “movement conservatives” and even “radical conservatives.” The point was to emphasize they were outside of and opposed to the reigning establishments—not only the liberal establishment but also the “well-fed Right,” in Buckley’s words, the regrettable allies of the northeastern (read: liberal) Republican establishment. . . .

Perhaps most noticeably, each New Right was impatient with the spiritlessness and excessive “modulation” (Buckley’s word) of the mainstream Republican Party, its typical politicians, big donors, and campaign strategists. These GOP elites reflected a ruling class that didn’t understand, or care to understand, how close America had drawn to the point of political crisis. As today’s young Right started saying some years ago, they didn’t know what time it is. WFB criticized this ruling class as the “Fabian operators . . . bent on controlling both our major political parties.” Today, the kids condemn what they term the “uniparty.”

4. At First Things, Nathan Pinkoski tracks the trans-Atlantic movement of America’s progressive ideology, now having just re-infected France, which has made abortion a constitutional right. From the piece:

This culture has trickled up into politics. Despite Macron’s claim that he occupies the reasonable center, much of his ideology is unabashed American progressivism. During Macron’s tenure as president, PISA educational rankings have recorded a massive collapse in the performance of French students in mathematics, reading, and writing. In response, Macron appointed a specialist in race studies as Minister of Education.

The constitutionalization of abortion is a fitting capstone for this transformation of French politics. The priorities of American progressivism are written into the fundamental law of the French Republic. The political campaigns of French activists become indistinguishable from their American counterparts. French activists celebrate abortion to make a point about the dangers of the far right; but since their own “far-right” politician, Marine Le Pen, enthusiastically supports this constitutional change, they are really thinking of Donald Trump and the dangers posed by the heartland of the United States. Macron is also set to copy the electoral strategy of the Democratic Party. In the upcoming European Parliamentary elections, the last significant election that implicates his presidency before he steps down in 2027, Macron’s team will round up the youth vote by campaigning on abortion.

5. At Law & Liberty, Jill Jacobson makes the devil’s argument about the Devil’s Advocate. From the essay:

Lone contrarians are rare in classrooms given the social costs. Professors can create the illusion of them, however, by reviving the Devil’s Advocate.

The Devil’s Advocate, a process where students are tasked with representing a side of an argument they disagree with, used to be a ubiquitous pedagogical tool. In-class debates were frequent and students were tasked with representing a particular view, whether or not they held it themselves. It was not uncommon for students to write a final paper weighing both sides of a particular issue.

Now, much of the academy views the Devil’s Advocate as unproductive, and perhaps harmful—opponents claim the tool emotionally taxes the students who disagree with the expressed perspective. . . .

The Devil’s Advocate should not be used as a front to share abhorrent opinions. Racism has no place in the classroom—or anywhere for that matter. But surely, a professor can identify a reasonable range of views that are defensible and worthy of debate without opening the floor to truly dehumanizing propositions. Racial questions are particularly difficult in our time, but harsh criticism of this pedagogical tool is not confined to hot-button issues like affirmative action. A Center for Conflict Resolution recently recognized that while the use of the Devil’s Advocate “improves group decision outcomes,” participants feel “a threat to their self-esteem, belonging, need for control and a meaningful existence, all of which are associated with poorer health and well-being.”

6. At Commentary, Michael Woronoff restates the case for free markets, buffeted from both the left and right. From the piece:

The attacks on capitalism from both left and right are based on many factual and conceptual errors. As these views take hold, the need for a full-throated defense of free markets has increased. Johan Norberg meets this need with his most recent book, The Capitalist Manifesto: Why the Global Free Market Will Save the World. It makes the definitive case for capitalism and repudiates common arguments offered against the system.

Norberg begins by cataloguing the immense economic and social benefits capitalism has conferred on mankind. For most of history, until just under 300 years ago, life was miserable for the bulk of humanity. Nearly all of Earth’s inhabitants lived in abject want with no hope of improving their lot. Global average income remained stagnant. Economic systems based on coercion were the norm. Then, beginning in the late-18th century, the liberalization of the British economy, transitioning from feudalism to capitalism, catalyzed the Industrial Revolution. The establishment of competitive markets and private-property rights facilitated the efficient allocation of resources, creating an environment conducive to innovation. The resulting rapid economic growth produced an unprecedented reduction in the percentage of the British population suffering from extreme poverty. As economies across the globe liberalized, the phenomenon spread.

Since then, capitalism has continued to benefit the world in an astonishing way. Norberg cites a review of more than 1,300 academic articles showcasing a resounding truth: “The correlation between economic freedom and societal outcomes [is] overwhelmingly positive: countries with freer markets have faster growth, better wages, greater poverty reduction [and] more investment.” Countries in the top quartile on a common index of economic freedom boast a per capita GDP seven times higher than countries in the bottom quartile. Those in the bottom quartile experience an extreme poverty rate that is a staggering 16 times higher than those in the top.

7. At Fairer Disputations, Leah Libresco Sargeant argues for having children, and against not having them. From the piece:

When we say no to children, we offer an individual and a societal no to hope in the future.

Many of the counsels against children are counsels of despair. Some believe that the world is too bad or too fragile or too uncertain to bring a child into. If we would hesitate to welcome a child into the world, we start to wonder if we should engineer our own exit. When I hear that despair, I contrast it with the experience of my family and many of yours who had children in tenements, in shtetls, in war zones, in the wake of pogroms. They had much less reason for hope for their children, but they were confident their love would not be wasted, even when their children’s lives and their own lives might be brief or full of suffering. When we say no to children, we say no not only to the vision of the particular future we anticipate for them, but the idea of a future at all.

When we say no to our connection to our future, we also weaken our link to the past. For many of us, it’s when we make the commitment to be the steward of something that will live beyond us—whether biologically as a parent, spiritually as a godparent, or by taking a role of responsibility in an institution—that we urgently feel the need to sift through the past and the traditions we have inherited. We have to deeply know what has been handed on to us in order to be able to pass those things on to those who come after us. Many of the counsels against children, which regard the human race or our particular culture as poisoned at the root, dodge this reckoning in favor of a bland, unconsidered no.

8. At RealClearPolicy, Jasmine Campos explains why—especially in college admissions, where a redux is afoot—objective standards matter. From the piece:

The original purpose of the SAT was to make higher education “more meritocratic.” Yet, since its creation, critics of the test have maintained the test is biased, as students of “color, low-income students, immigrants, and other historically excluded groups scored lower on the exam.” While the test was an attempt to standardize admissions procedures and allow more access to higher education, the debate over the value and bias within such testing continues today.

The pandemic allowed universities to use public health as a reason to get rid of a system they already considered biased and racist. The National Education Association published an article from 2021 titled “The Racist Beginnings of Standardized Testing” which discusses how standardized tests are not just an example of racism, but an instrument and inherently biased systems. Brookings made a similar point in a 2020 article titled, “SAT math scores mirror and maintain racial inequity.” Inside Higher Ed wrote about “The SAT and Systemic Racism,” stating that it is a simple perpetuation of past crimes. Some say the recent Supreme Court decision means that the only way to legally be allowed to encourage underrepresented groups is to get rid of testing requirements.

Yet, now administrators are changing their tune once again. Jeremiah Quinlan, dean of Yale undergraduate admissions, said that strong test scores will not hamper economic equality, but will in fact have the opposite effect of boosting those from low socio-economic backgrounds. He even went so far as to claim that students attending high schools with less resources have little in their applications to prove their readiness. Therefore, when they are able to include a score, “they give the committee greater confidence that they are likely to achieve academic success.”

9. At Providence Magazine, Phillip Dolitsky contends that military ethics must take guidance from the economic “seen and unseen” principle. From the analysis:

It is a fundamental truth about the nature of war that the enemy always gets a say. That is just as true within military ethics as with military doctrine and planning. Historian David Lonsdale, commenting on the military strategy of Philip II and Alexander the Great, notes that “if one treats cultural and moral concerns as the prime consideration in war, then one may cede the advantage and initiative to an enemy who is in harmony with the true nature of war.” Similarly, Carl Von Clausewitz, the greatest military theorist of all time, recognized this truth that “if one side uses force without compunction, undeterred by the bloodshed it involves, while the other side refrains, the first will gain the upper hand.”

Hamas and other terrorist groups thrive off of the ethical concerns of liberal statesmen. While we laud the seen reality of adhering to such ethical standards, we should also be aware of the unseen effects, where opting against some violence today really amounts to choosing more violence tomorrow. Moral philosophers who insist that leaders adhere to “absolute” moral truths congratulate themselves for pressing for peace when they are merely kicking the can down the road for the next generation.

Ethical considerations in war are tragically paradoxical: the more ethically constrained military campaigns and operations are, the longer evil reigns. The opposite is likely true as well: the more brutal war is, the longer peace can prevail. The decisive victory at Chaeronea and at Carthage, and the failure to maintain the peace after WWI serve as a small sampling of this paradox.

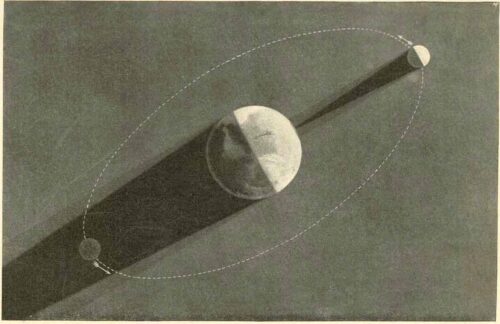

9. At The Lamp, Peter Hitchens reflects on nuclear deterrence and the aging gadgetry upon which it depends. From the beginning of the piece:

With a large, soft plop, a significant part of Britain’s supposed nuclear deterrent recently fell into the deep waters off Florida, not far from Cocoa Beach. Embarrassingly, the U.S. Navy looked on, as these tests take place pretty much under the supervision of the American fleet. The Russians probably knew too. One Royal Navy submarine captain once told me how, after a successful missile launch, the international frequency of his radio crackled to life as a Russian-accented voice said, “Congratulations, Captain, on your successful test!”

But lately there have not been many such successes. In 2016, another of the American Trident missiles, which His Britannic Majesty leases from the United States, had whizzed off in the wrong direction (towards the U.S.A., alas) and had to be destroyed while still in the air. Of course both were without their appalling nuclear warheads. But even unarmed, these things are expensive and you cannot just keep testing them. If I were whoever is supposed to be deterred by this elderly assembly of gadgets, tangled wiring, steam, salt, and rust, I might not be as nervous or as cautious as I was intended to be. Though in any case, who is all this aimed at? I cannot work out which nation cares enough about us. And could we use it? I shouldn’t think so; in fact I am sure that we would not. Who would take such a responsibility for killing so many people so horribly, when the whole point of the thing had already disappeared?

11. At The Public Discourse, Jamie Boulding explains the importance of friendship in the intellectual life. From the beginning of the reflection:

“The best thinking has been done in solitude.” In our technological age of isolation and anxiety, Thomas Edison’s view of the intellectual life persists. Two of the greatest figures in the history of science, Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein, were both introverts who associated being alone with thinking clearly. The image of the academic secluded in his ivory tower, or the scientist sequestered in her laboratory, looms large in our cultural imagination. With the enforced isolation of COVID-19, the growth of remote working, and the emergence of powerful AI tools like ChatGPT, we increasingly reduce intellectual pursuits to little more than private projects.

It was not always this way. Intellectual friendship—the idea that the best way to think clearly is to think together—has been foundational throughout philosophical history. Plato’s works are presented in dialogue form, suggesting that truth-seeking is communal, cooperative, and best practiced within relationships of friendship and love. (As its Greek root philosophia reminds us, philosophy is the love of wisdom. Aristotle observed that all men desire to know.) For Aquinas, opening ourselves to others is a prerequisite for opening ourselves to the truth: “In order that man may do well, whether in the works of the active life, or in those of the contemplative life, he needs the fellowship of friends.”

Today, how many people think of the intellectual life primarily in terms of fellowship, friendship, and love? Somehow, it has come to be seen in terms of what we know rather than who or what we are—or, as a philosopher might put it, in terms of epistemology rather than ontology. Meanwhile, for those who don’t simply dismiss “intellectual friendship” as a contradiction in terms, other doubts might remain: Is it just about well-meaning but unfocused conversations? Worse still, might it be ideologically self-serving to link the intellectual and the relational?

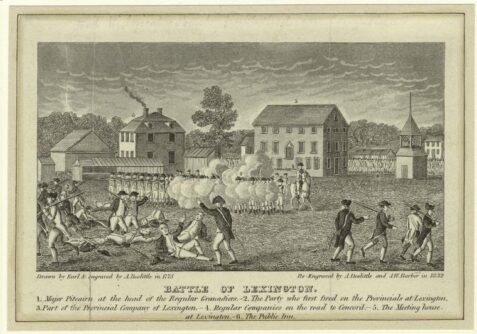

12. At National Affairs, Dan Currell and Elle Rogers condemn the trend in American History education that eradicates the Founding. From the essay:

The real problem with the 1619 Project, however, is not what it gets wrong, but what it erases. The project removes beliefs and ideas from our history, presenting the American story as a series of tactical moves carried out by groups trying to maximize their own economic advantage. What our forebears believed about what they were doing, how those beliefs motivated them, and how they influenced later generations is simply not part of the story.

This aspect of the 1619 Project is not new. For decades, young Americans have learned an increasingly Marxist version of their nation's story in books and videos, and have advanced the plot to the present day in classroom discussions. Principles like equality, governance by the people, and natural law now make only rare and unexplained appearances in even the most advanced U.S. history curricula. Like the three witches of Macbeth, our most consequential ideas show up at key moments, but their relationship to the main action is never clear.

We need to restore the connection between what Americans did and what they believed—to take their words seriously on the question of why they made the decisions they made. A look at today's dominant history texts suggests we should focus as much on restoring what is missing as we do on correcting what is wrong.

Lucky 13. Wham BAM: At KING-5 TV in Seattle, Jim Dever reports on a successful fundraiser that has staved off the closing of a local museum. From the beginning of the story:

They resemble brightly colored plants, massive sponges and draped sheets of fabric. But the pieces on display at the Bellevue Arts Museum’s “Washi Transformed” exhibit are all constructed from traditional handmade Japanese paper by contemporary artists.

It’s just one of hundreds of exhibitions presented by Bellevue Arts Museum over its nearly 50-year history, an Eastside arts legacy now threatened with extinction. Past mismanagement and the challenges posed by the pandemic have left the museum severely underfunded.

Last month, BAM announced it was in financial straits and launched a six-week fundraiser to come up with $300,000. The public has responded overwhelmingly.

“We’ve been incredibly successful,” said Kate Casprowiak Sher, the new executive director of the museum.

Bonus. At The Daily Yonder, Ilana Newman tells of a “Brain Gain” in rural America. From the piece:

For many people, leaving a rural place is a rite of passage. From higher education to looking for love, many think they have to leave to pursue the rest of their lives. This narrative contributes to the often repeated and not all true story that our rural communities are dying.

According to University of Minnesota researcher Ben Winchester, rural communities are actually gaining residents—mainly above the age of 35—in a trend that he calls “brain gain.” Winchester also said the “brain drain” trend of 18 years olds leaving their home communities is not only a rural trend. Overall, between 40-60% of all kids end up leaving their hometown. “When you’re 18-25 you’re generally very individualistic,” said Winchester.

So who is choosing rural and why?

For the Good of the Cause

Uno. Mark your calendar! A new AmPhil “Scotch Talk” will be coming at you (via Zoom) on Tuesday, April 16, from 3:00 to 4:00 p.m. (Eastern), with the quartet of Jeremy Beer, John LaBarbara, Jason Lloyd, and Boaz Witbeck on hand to share buckets of wisdom about finding and fostering Major Gifts. Get the ice, the tumbler, and the libation ready—but make sure you sign up, which you can do right here.

Due. Save those dates! October 23-24. And mark the location! Pepperdine University in Malibu, CA. Why? Because that’s when and where the Center for Civil Society will be hosting its 2024 Givers, Doers, & Thinkers conference, this one on “K to Campus: How the Education Reform Movement Can Reshape Higher Ed.” Agenda and speakers will be announced soon, but registering, getting info, and all such stuff can be done and found right here.

Department of Bad Jokes

Q: Why couldn’t the flower ride a bike on the first day of spring?

A: It didn’t have petals yet.

A Dios

Palm Sunday is upon many Christians (our Eastern Orthodox brethren have weeks to go). This was always a special day, de gustibus: By tradition, the little Italian grandmother would make this wonderful dish, she called it spitsad, but some sources have it as spizzato. No matter its name, the combination of lamb chunks (many still attached to cleaved bones), egg, and greens, baked in a big pan, was delicious! Below her recipe, sent by a dear relation who had it (scrawled in Gran’s handwriting) on an ancient index card. You may get it right on the third attempt, and when you do . . . momma mia!

Ab’t 2 lbs lamb, not too small pieces

Ab’t 3 lbs dandelions or chickory

Ab’t 9 eggs or enough to cover . . . with cheese (plenty of grated parmesan), parsley, pepper beat well

Fry meat until brown add water and let cook (same as stew)

Cook dandelions save water

Place meat in roasting pan

Spread veg(etables) add some of water, enough so that eggs will cook

Bake in 375 over until egg is settled

May He Who Feeds the Sparrow Nourish Our Souls,

Jack Fowler, who watches birds while receiving emails sent to jfowler@amphil.com.